If you’ve ever been to Washington, D.C., in the middle of July, you know how hot and humid the city can feel. In 30 years, this is what Toronto’s summer months could feel like.

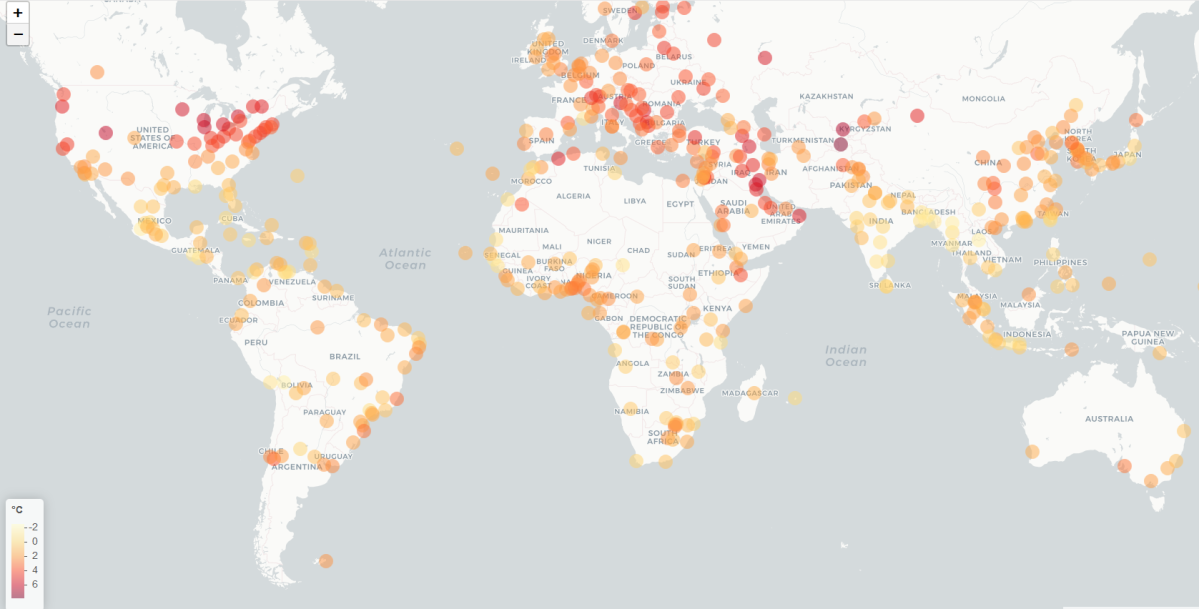

That’s according to a recent study released by the Zurich-based research group Crowther Lab that aims to predict what cities will feel like in 30 years by comparing their future climates to the current weather in other cities.

The report predicts Toronto could feel like Washington, D.C., by 2050, with a temperature increase of 6 C above the city’s current average highs, and reaching highs of 31 C in the city’s warmest months.

Other Canadian cities were no exception. According to the report, Ottawa will most closely resemble Pittsburgh, Pa., Montreal will resemble Cincinnati, Ohio, and Calgary will resemble the Chinese city of Lanzhou by 2050.

The analysis pulled data from 520 cities, which are home to at least a million people. Over 70 per cent of cities included in the study are expected to experience warmer climates, and more than 20 per cent of the cities are expected to experience weather conditions that don’t currently exist in those locations.

How will life in cities change?

For Toronto specifically, the study predicts a temperature increase of approximately 6 C during the warmest month of the year. Calgary, Montreal and Ottawa also saw similar increases. Montreal’s warmest months will see an increase of almost 6 C as well, bringing its high to 31.03 C; Ottawa will see an increase of almost 6 C in its warmest months as well, bringing its high to 30.26 C; and Calgary will see an increase during its warmest periods of 3.8 C, bringing its high to 26.83 C.

While this may not sound like a lot, experts warn that a few degrees Celsius could mean big lifestyle changes for the residents of these cities.

“That’s very significant,” said Raymond Bradley, director of the Climate System Research Center at the University of Massachusetts.

READ MORE: Ottawa investing $250K for green economy hub in Peterborough to improve businsses’ sustainability

Overall, the report predicts that if rates of carbon emission remain unchanged, the earth is expected to increase in temperature by between 2 C and 2.5 C by 2050. It also goes on to state that the costs of this level of warming are expected to exceed US$12 trillion by this time.

Dustin Benton, head of the U.K. environmental group Green Alliance, adds that warmer places have built out the necessary infrastructure to sustain the heat as opposed to places that are cold.

Get daily National news

“The thing to bear in mind is that places that are warmer have developed physical infrastructure that looks and feels quite different to places that are cold,” he said.

“If you think about British housing stock, for example, even today, 20 per cent of U.K. homes are prone to overheating, and that’s in a world which has only warmed about one degree above pre-industrial levels.“

WATCH: Here’s where the federal parties stand on the carbon tax

Benton added: “It will probably require fairly extensive building retrofits, and that could be anything ranging from changing the passive solar gain of buildings.”

According to the report, many of the cities profiled are expected to shift towards subtropic temperatures. Because of this, Benton also notes that in addition to adapting living spaces for people, wildlife in many regions of the world could change drastically.

“We will need pretty extensive adaptation in cities in order to provide a good living space for people, and that will involve a combination of significant additional vegetation,” he said.

Can we slow the warming down?

The only way to slow the warming of cities down, according to Benton and Bradley, is to double down on reducing emissions. However, experts have told Global News in the past that it may be too late to reverse the damage already done.

The United Nations released a report last October warning that there will be irreversible, significant changes — including the entire loss of some ecosystems — if the world doesn’t take immediate action to cut greenhouse gas emissions far more quickly than current efforts are achieving.

Global News has previously reported that this translates to limiting the increase in the average global ground temperature to 1.5 C, rather than 2 C as specified in the 2015 Paris climate change accord. Canada specifically was tasked with reducing its emissions by half in 12 years.

- Alberta increases fines for distracted driving, other offences by up to 50 per cent

- Troubled youth treatment centre Venture Academy ‘winding down’ operations

- Man charged with first-degree murder in killing of Montreal convenience store owner

- Wrong turn at Ont., border leads to 6 fake passport seizures, 3 charged

“We’ve tried before to cut our emissions. There was the Kyoto accord back in the 1990s, and we were never able to meet those targets. We haven’t made much progress towards meeting the Paris targets,” Kent Moore, a professor at the University of Toronto, explained at the time.

READ MORE: ‘Virtually impossible’ for Canada to cut emissions in half by 2030 to meet UN goals: experts

“I’m extremely pessimistic about whether we can do that or not,” Moore added.

However, Benton dismisses this attitude as “defeatism.”

“Of course we can turn our climate change policy around … it’s eminently achievable. We probably can actually go faster,” he said.

Carolyn Kim, an urban development analyst with the Pembina Group, notes that key opportunities for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions lie in the transportation and oil and gas sectors.

“One area that we focus on is how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the transportation sector given that both in Ontario and Canada, emissions in the transportation sector represent a quarter of our total emissions profile,” she explained, though Kim also noted that transportation is still second to Canada’s oil and gas sector.

Why is this kind of research important?

Contextualizing climate change through the use of current comparisons has been attempted in the past.

The University of Maryland produced a similar study this past February using data from 540 cities that predicted North American climates will feel “substantially different” than they do today — closer to the humid, subtropical climates of the Midwest.

This study forecasted a similar — sometimes more extreme — outcome for Canadian cities, with Toronto projected to feel more like New Jersey by then with a temperature increase of 5 C in its warmest months.

WATCH: Climate change could lead to triple frequency of severe air turbulence

The study projects Ottawa’s warmest average temperature will rise by 6 C, Montreal’s warmest temperature will rise by 9.5 C, Calgary’s warmest temperature will rise by almost 6 C and Vancouver’s warmest temperature will rise by just over 4 C.

Fred Michael, the former Director of Carleton University’s Institute for Environmental Sciences, warns against trying to predict climate conditions too far into the future.

“Climate change is a complex issue and something that has been happening continuously since the beginning of time. There is a reason why meteorologists use a rolling decade by decade ‘normal’ for comparison purposes.”

He also notes that the study fails to mention that cities themselves are “heat sinks,” which change the environmental conditions of the areas around them., meaning that rural areas will be affected differently.

Bradley however, praised the concept of using comparisons to communicate the urgency of climate change to citizens around the world.

“We’re talking about one or two degrees Celsius changes, and nobody really appreciates what that means. But if you can say to somebody: ‘Boston is going to feel like South Carolina,’ then they get it.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.