Growing up, Puneeta Varma and her military family moved often, which meant she celebrated holidays like Diwali and Holi in regions across India.

But as she recalls years later, they were extravagant, multi-day celebrations and statutory holidays in nearly all regions of the country.

“People started celebrating way before the official start of the holiday, shops would get all dressed up, there would be street markets,” she recounted to Global News.

“Walking down a street in Delhi, you could just feel the holiday.”

In Toronto, where Varma and her husband are now raising two daughters, aged 13 and eight, things are different. The celebrations shorter, less extravagant — and often not on the days of the actual holiday.

Puneeta Varma celebrating Diwali.

It’s a problem many immigrants, newcomers, and Canadians from religious and cultural minorities face in the country. How do they fit their holidays into hectic schedules, when the country’s statutory calendar — which is largely focused on Christian celebrations — often doesn’t leave room?

The answers range among communities, families, and individuals.

For Varma, it has meant moving schedules around, creating new traditions where older ones no longer fit, but also holding on tightly to time-honoured practices that are too important to change.

Of course, there are some things that can’t be helped, such as Canadian weather that forces many of the traditionally outdoors activities to be held inside.

READ MORE: A look at Diwali celebrations around the world

Then, there are scheduling conflicts.

“In my memory, these holidays have mostly been on a weeknight or weekday, so there isn’t much time that we have around our daily schedule. We usually tame our celebrations down during the week.”

Instead, the family celebrates on the following weekend, which isn’t ideal for holidays like Diwali that are meant to include prayer on a specific day.

Varma says all this often makes her wonder whether the holidays she grew up with and cherishes will remain part of her daughter’s lives.

Puneeta Varma’s daughter creating rangoli designs on Diwali.

“I do wonder whether they’ll carry on or not, and I know for sure it will be different,” Varma said, noting that she’s not too concerned about small traditions, but rather that her children value the holidays.

While celebrations aren’t the same, Varma says the family has found a new joy in Canada — sharing their traditions with others.

“The good part about having a festival on a weekday is that kids can talk about it in their school,” she said, adding that she was recently invited to her younger daughter’s class to explain what the holidays mean.

“It’s easier when the kids are younger, because I see with my older one, middle school is so structured around tests and assignments. They have all these boxes they need to check and multicultural values can be considered as nice to have, but not essential.”

In much of the western world, Christian holidays dictate school and work schedules. But in some diverse cities, that is starting to change.

Get daily National news

In 2015, New York City Mayor Bill DeBlasio added Islamic holidays Eid al-Adha and Eid al-Fitr as official days off for school children.

He said it was a move that “respects the diversity of our city.”

While systemic changes such as the one in New York are rare, some cities can be more accommodating than others.

WATCH: Calgarians celebrate Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights

That’s something Jennifer Fox has experienced in various stages of her life.

Fox spent much of her childhood in Thornhill, Ont. The large Jewish population meant there wasn’t much explaining to do, and teachers understood many students would be taking the day off.

“They never really did much teaching those days, it was kind of a fun day for other students while the rest of us were at the synagogue,” she told Global News.

But then, as she grew older, Fox says she began noticing the challenges.

READ MORE: Holiday food traditions from around the world

Fox attended university in Halifax, where she often had assignments due on religious holidays. She asked for extensions, but sometimes they weren’t granted.

“Then, when I started working, I was expected to take vacation days,” she said, noting that for Rosh Hashanah, that often meant three out of 10 yearly vacation days.

The public relations and communications professional recounted some instances at previous jobs where she faced trouble.

“They said, well, you get Christmas off. And I said, but I don’t celebrate Christmas.”

“If the office was open and if anybody else was working, I’d work Christmas because it doesn’t mean anything for me,” she noted.

Toronto-based employment lawyer Muneeza Sheikh says employers should be providing religious accommodation to their workers as best as they can.

Sheikh explained that the Canadian Human Rights Act and provincial codes, such as the Ontario Human Rights Code, call for religious accommodation.

WATCH: Montreal elementary students share Passover traditions

She noted that is true regardless of whether a holiday is or isn’t a nationally or provincially recognized one.

“Our human rights legislation, both provincially and federally, does not only apply to workplaces but also applies to your schools as well,” she said.

But it’s not exactly as simple as demanding days off.

According to the Ontario Human Rights Commission’s website, when a religious accommodation request is made, the individual should be able to explain how it is related to their religion. They must also be able to explain how the accommodation will affect their ability to do their job, or other tasks at hand.

Those providing accommodation may need to ask for more information, but should also be mindful of privacy, the commission explains.

WATCH: Eid Al-Adha celebrated around the world

If a request is denied, an employer should be able to show that a reasonable attempt was made.

And if someone feels like a reasonable request has been denied, Sheikh explained there are steps that can be taken, such as formal complaints to a human rights tribunal.

READ MORE: Why Muslims fast during Ramadan

And institutions are becoming more aware of the importance of scheduling events around holidays. Most recently, the Law Society of Ontario apologized after scheduling its barrister exam on June 4 this year, which was Eid day.

“We recognize that the scheduling of the Barrister Examination on Eid was not in keeping with our commitment to inclusion in the profession,” a release from the society read.

But having days off work or school isn’t the only obstacle minorities living in Canada face. Sometimes, preserving traditions is a community effort.

That couldn’t be truer for Prince Edward Island’s small but growing Muslim community.

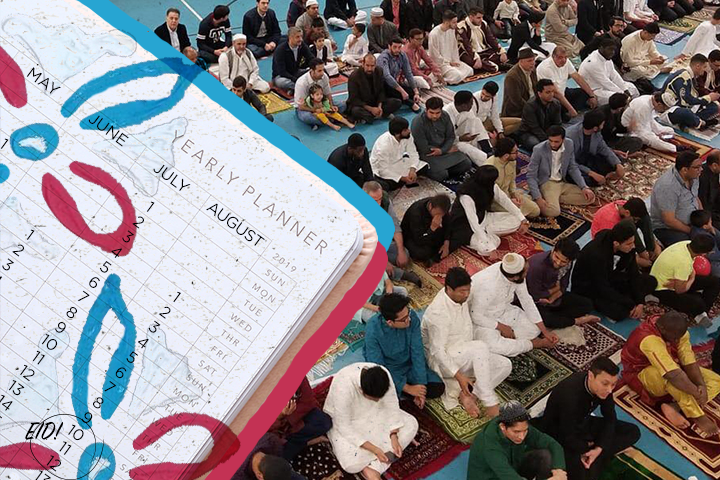

Eid prayers held by the Muslim Society of Prince Edward Island this year.

Zain Esseghaier, who works at the University of Prince Edward Island, is part of the congregation at the Muslim Society of Prince Edward Island, which is also referred to as Masjid Dar-As-Salam.

The small P.E.I. community has grown in recent years, through immigration and the arrival of Syrian newcomers — many of whom Esseghaier says needed a place to come together and connect, especially during the holiday seasons.

“Maybe not in Toronto, but in smaller places such as ours, there has been no precedent, and we are the first generation to establish certain routines and expectations,” he explained to Global News.

Part of the role the mosque has played is educating students and newcomers on their rights regarding religious accommodation.

Eid celebrations previously held by the Muslim Society of Prince Edward Island.

“For newcomers, sometimes the situations may not be very clear, so we just make sure they are aware of their rights, and the obligations employers have to accommodate,” he said.

“People should be able to celebrate their Eid,” Esseghaier said, noting that it’s important the celebrations happen on the real holiday.

“The weekend is not Eid day, Eid day is Eid day.”

Because Eid is held on a specific day of the Islamic calendar, Essenghaier explained delaying it means it loses some of its meaning.

To encourage those in the community to celebrate, the mosque organizes Eid prayers, barbecues, carnival activities and presents for kids.

He noted that for him — much like Varma nearly halfway across the country — holding on to traditions comes down to the children.

“When we make it a full day of celebrations for the kids, on the actual day, it creates lots of memories,” he said. “And our children, when they grow up, they will remember.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.