After a three-month plunge at the end of 2018, financial markets are headed back up. Less than two weeks into 2019, the S&P/TSX Composite, Canada’s benchmark stock market index, is already up four per cent, after a 12 per cent drop last year.

READ MORE: Stock markets slide after Apple reveals declining iPhone sales in China

If you’re sitting on a pile of cash, you’re probably wondering whether it’s time to buy up some stocks. Perhaps you’ve gradually sold most of your investments as the market turned south last year. Or maybe you’re ready to make your very first investment and are waiting for the right time to jump in.

Either way, the question is: Are the markets starting another rally or will they soon resume their slide?

The short answer is no one knows and you don’t need to worry about it, anyway.

WATCH: How regular investors should navigate the expected rollercoaster market in 2019

Even economists can’t tell when a market recovery has started until it is already underway, Nancy Graham, portfolio manager at PWL Capital in Ottawa, notes in an episode of her YouTube series No Dumb Questions.

The thing is, if you’ve pulled out of the market when it was sliding, “instead of already being there, ready to capture the upswing from the moment that it begins, you’re left trying to figure out when it feels right to get back in.”

READ MORE: Bank of Canada keeps key rate at 1.75%, downgrades economic forecast

Everyone knows the basic rule of investing: don’t buy high and sell low. But even trying to do the opposite — buy low and sell high — is a recipe for “lower expected returns and higher levels of anxiety,” according to Graham.

“Market-timing doesn’t work,” she told Global News via telephone.

Even the pros fail at it.

WATCH: Investing with robo advisors during recessions

Take actively managed mutual funds, whose highly paid portfolio managers are constantly trying to beat the market. As of the middle of last year, the vast majority of these funds in Canada were trailing the main Canadian stock market indices, according to a report compiled by S&P Dow Jones Indices.

Get weekly money news

“Over a one-year horizon, the majority of active managers once … failed to beat their respective benchmarks; six of the seven fund categories underperformed,” reads the report.

And that was no accident. Over a 10-year period, nine out of every 10 funds had lower returns than the market index they were trying to beat, the same paper indicates.

You’re much better off staying invested or not worrying too much about when to get started if you’re an investment newbie just starting to save for retirement, Graham said.

WATCH: Should you invest with a robo advisor?

Roger Young, senior financial planner at T. Rowe Price, a U.S. investment firm, breaks this down further by looking at the last big stock market crash.

The stock market dive that kicked off the financial crisis in late 2007 and lasted until early 2009 was one of the steepest in history, with the S&P 500 Index shedding almost 57 per cent of its value. The index did not climb back to where it stood at its October 2007 peak until five years later.

READ MORE: Jeff Bezos’ divorce news gives Amazon investors ‘pause for thought’

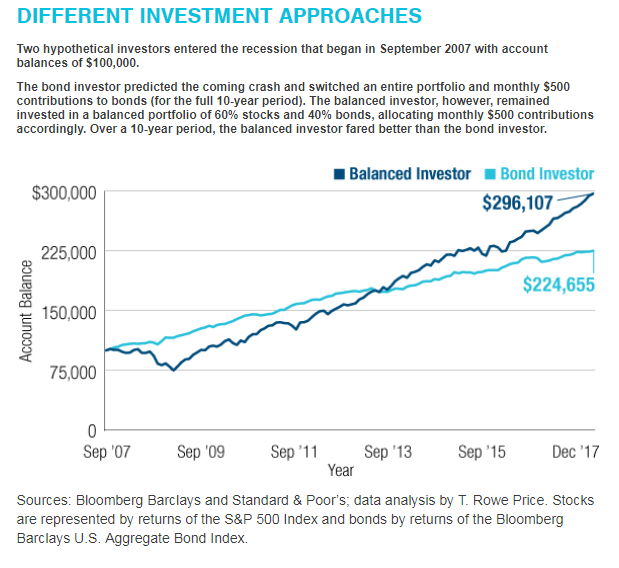

Young compared two hypothetical investors. The first saw the crash coming and sold all her stocks in September 2007, switching to an all-bonds portfolio. The second rode out the downturn with a mix of 60 per cent stocks and 40 per cent bonds. Both started with a portfolio worth $100,000 and stuck to $500 monthly contributions.

While the bond investor would have seen better returns for several years after the crash, by the end of 2017 she would have been tens of thousands of dollars worse off. Over a 10-year span, the bond-only portfolio would have grown to $224,655 compared to $296,107 for a combo of stocks and bonds.

Young believes the investor who managed a perfectly timed exit in 2007 would have been worse off in the long term even if she had attempted to re-enter the stock market.

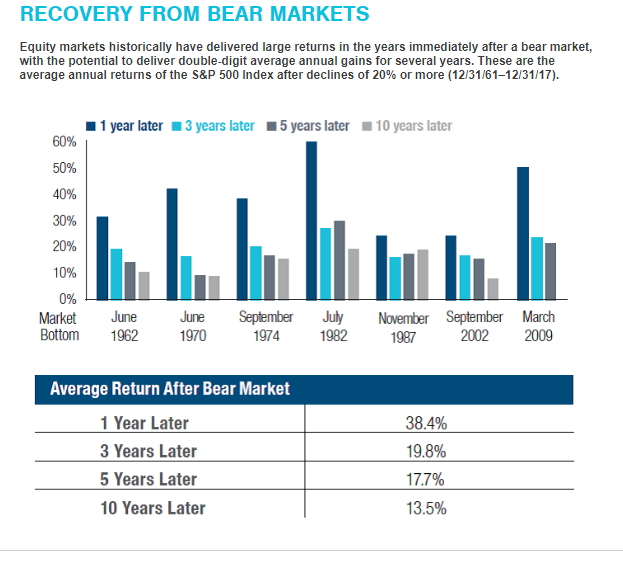

Not only are market recoveries difficult to time, but by getting in late, investors tend to miss the large gains that typically happen in the early stages of a rebound. Historical data shows that the average return after a bear market (a decline of 20 per cent or more in major stock indexes) was 38 per cent in the first year of the recovery, compared to less than 18 per cent five years later.

But staying invested through wild ups and downs is easier said than done. Both when we get excited as the market smashes through record highs and when we get sweaty palms at the sight of our shrinking money piles in a downturn, “psychology works against us,” Graham said.

Sailing through the turbulence requires having some firm coordinates in the form of a well-thought-out investment plan, Graham added.

For example, say, you’ve committed to keeping 60 per cent of your money in stocks and 40 per cent in bonds — the typical investment mix for people with a medium tolerance for market swings. Sticking to your coordinates means you should be selling some of your stocks when the market is on a high — because pricier stocks are now worth more than 60 per cent of your portfolio. Vice versa, you should buy stocks when the market tanks — or at least acquiesce to your investment advisor doing so for you.

READ MORE: 7 hacks to save more — without the mental struggle

Sometimes, though, going through a rough patch will cause you to realize that you overestimated how much you’d be able to stomach. In that case, you might want to revise your coordinates, perhaps switching to a less bumpy 50-50 split between stocks and bonds, Graham said. You’ll lose some money by implementing that adjustment, but it’ll be worth it if it means realigning your investments with your actual risk tolerance.

WATCH: Finding the right financial advisor for you

Re-setting your investment navigator, though, should be done with a clear mind and, possibly, a chat with your advisor. It’s a long-term change of course, not a temporary tweak to be reversed when the going gets easy again, Graham warned.

Another tip is to head below deck once your route is set. There isn’t much point in following the daily swings of the market or paying close attention to the headlines, Graham said.

“But we all have to recognize, there are $400 billion a day of equities traded,” she added. “There isn’t really an explanation.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.