WARNING: Disturbing details.

An orca killed a baby killer whale in B.C. waters, in what is believed to be the first infanticide among the species, say the findings of a research paper published in Nature this week.

And it was all because the orca wanted to mate with its mother, scientists believe.

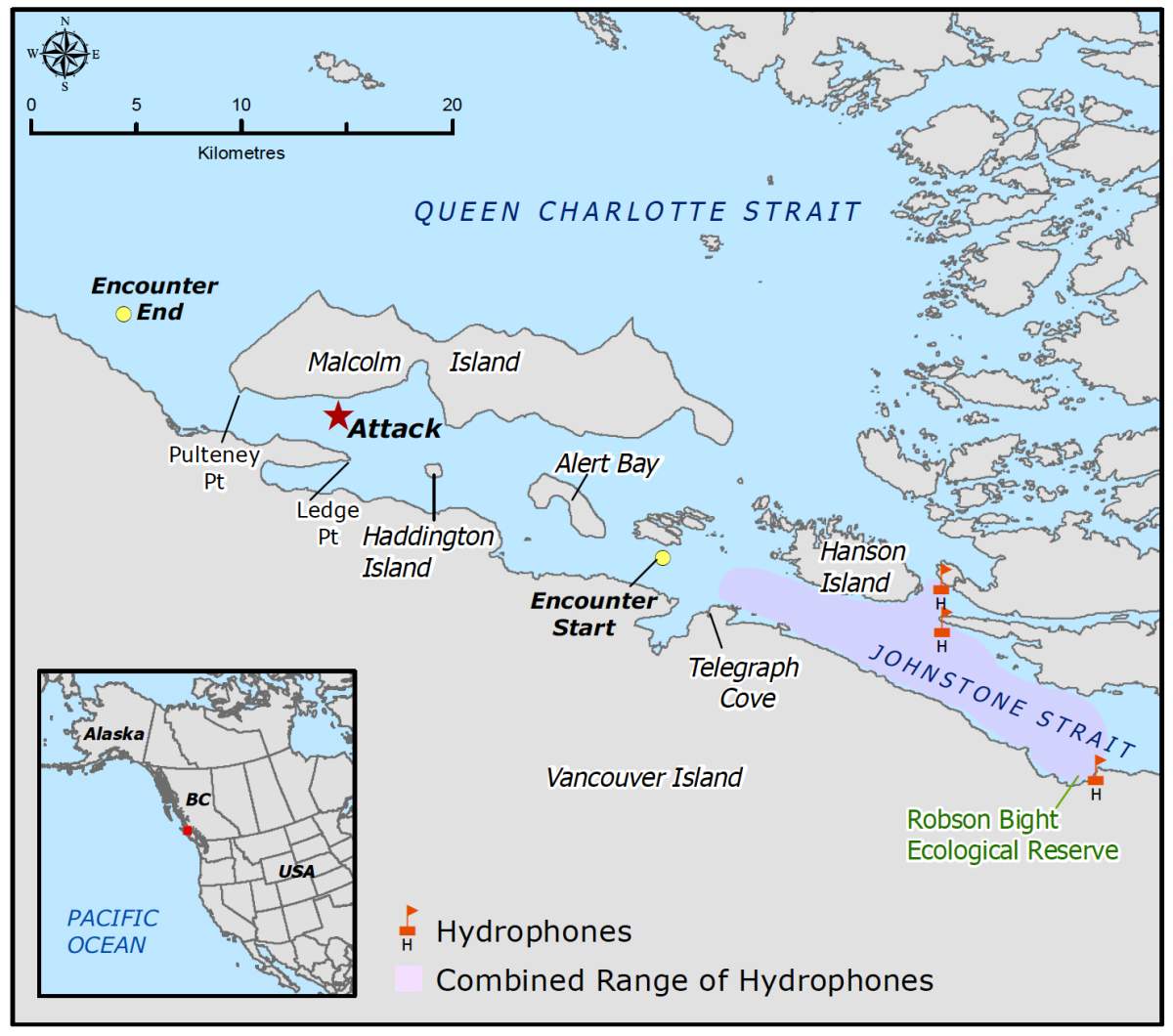

The encounter was spotted in the area of the Johnstone Strait north of Vancouver Island on Dec. 2, 2016.

WATCH: Original video of the incident captured by researchers in the western Johnstone Strait

It began at about 10 a.m., when orca sounds were heard at a hydrophone station near Robson Bight.

About an hour later, a research boat set out from Alert Bay and found northern resident, or Biggs killer whales travelling west in the western Johnstone Strait.

There were two groups of orcas.

One consisted of a mother and her adult son. They were following about 200 metres behind three members of a family of whales with whom they would soon find themselves in a bloody conflict.

One of the whales they were following had wounds from the teeth of another whale — some of which were bleeding.

Then, about a half-hour later, researchers spotted more whales belonging to the same family. There was a mother, her two daughters and a newborn baby.

The family of orcas came together close to Haddington Island, about a half-hour after that — but the pursuing mother and her son stayed about 200 meters behind them.

Get breaking National news

READ MORE: Fishing group has close encounter with a large pod of orcas

Several more minutes went by and “erratic movements and splashing suggestive of a predation event were observed,” according to the paper.

The male that earlier gave pursuit was moving away from the other orcas as they circled him.

The newborn baby was not surfacing next to its mother.

Researchers soon noticed the newborn’s body being dragged by the male pursuer, the baby’s carcass trailing beneath his jaw.

And now, the newborn’s mother looked to be after him.

She appeared to chase the male as his own mother tried to move between them, and together the whales sent off “intense vocal activity” that could be heard through the hull of the research boat.

The newborn’s mom rammed the male hard enough to “send blood and water into the air” and to make his blubber “shake like a bowl of Jello,” according to researchers.

The encounter calmed down at about 12:43 p.m., when the pursuing male and his mother moved away from the area, the latter dragging the newborn baby’s body by the tail.

She was later spotted holding the baby’s left pectoral flipper in her mouth.

WATCH: Extended — B.C. researchers witness aftermath of orca infanticide

The pair were spotted with the newborn’s body as late as 4 p.m., but the observation was called off due to the onset of nighttime at 4:15 p.m.

READ MORE: It doesn’t get more B.C. than an orca breaching in front of a kayaker’s face

Researchers later determined that the pursuing male drowned the baby by gripping its tail with his teeth, and giving it no chance to surface for air due to his “consistent forward motion.”

They believe the attack happened due to “sexual selection,” a phenomenon in which a male commits an infanticide, not only to mate with the baby’s mother, but also to “remove the progeny of a competing male from the gene pool,” study co-author Jared Towers told Global News.

“I think this behaviour was motivated by a desire to breed,” he said.

Orcas tend to lactate for up to two years after they give birth — and they don’t ovulate while they’re lactating, he added.

“With knowing this female had just given birth, and knowing if that infant was killed, that ends lactation,” Towers said.

“Then she can become fertile again quite quickly. There’s an opportunity there for a breeding male to have his genes get passed along to the next generation.”

READ MORE: Killer whales hunting near Washington state put on amazing aerial show

The researchers also weren’t surprised to see the whale’s mother work together with her son to kill the newborn and assist her son in finding a mate.

“In sympatric populations, post-reproductive female killer whales increase the survival of adult sons by sharing ecological knowledge and prey with them,” the paper said.

Their working together was likely motivated by the potential to improve their “inclusive fitness” — that is, their genetic success thanks to cooperating.

“This benefits inclusive fitness of the female because a positive relationship exists between reproductive success and age in male killer whales,” the paper read.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.