Finding a place to rent in Metro Vancouver is tough enough.

But almost half of those who have found a place are straining their finances to keep those roofs over their heads, according to data contained in Wednesday’s Census release.

Coverage of renting in Vancouver on Globalnews.ca:

This week, Statistics Canada released “Housing in Canada: key results from the 2016 Census,” a dataset showing how much the country’s housing landscape has changed over the past decade.

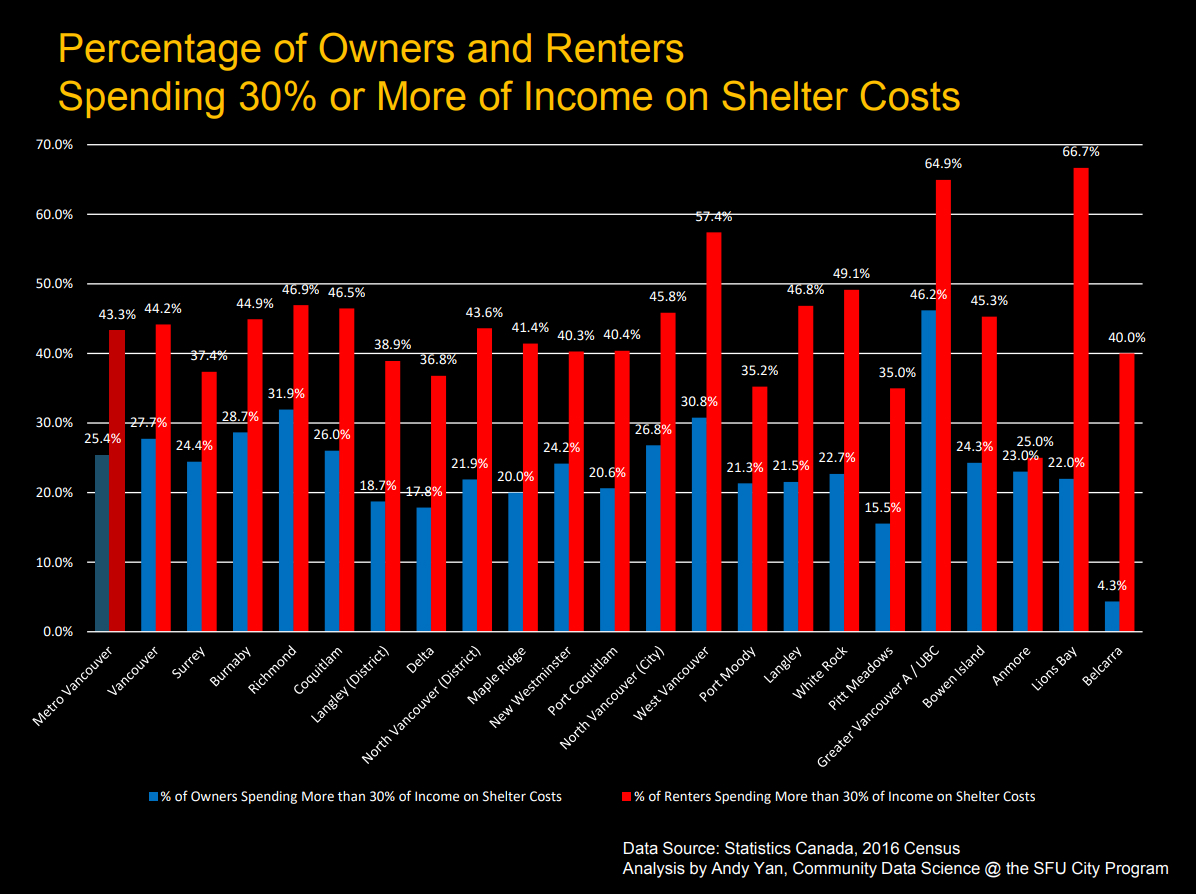

Data contained in the release showed that just over 43 per cent of renters are spending 30 per cent or more of their income on shelter in the Vancouver Census Metropolitan Area (CMA).

The CMA covers an area that includes municipalities such as Vancouver, Richmond, Surrey, North Vancouver and Langley.

The Census release showed that, out of 348,700 renters identified in the Census, 150,505 (43.2 per cent) were spending 30 per cent or more of their income on shelter costs in 2015.

The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) says housing can be considered affordable if it takes up less than 30 per cent of before-tax household income.

Therefore, more than 43 per cent of residents in the Vancouver CMA were living in housing that can’t necessarily be considered affordable.

READ MORE: North Van developer says the industry needs to do more to help with the housing crisis

Census data compiled by Andy Yan, director of the SFU City Program, shows varying levels of renters living in “unaffordable” housing across Metro Vancouver’s municipalities.

Get breaking National news

In the City of Vancouver, 44.2 per cent of renters were living in housing that took up 30 per cent or more of their income.

The highest share of renters living in housing they couldn’t afford was observed in Lions Bay, where the share was 66.7 per cent.

The lowest share was witnessed in Anmore, where it was 25 per cent.

But that’s not the only figure suggesting that Metro Vancouverites are spending more than they can technically afford on a place to live.

Data crunched by the B.C. Non-Profit Housing Association (BCNPHA) shows that 22 per cent of renters were spending at least half of their before-tax income on shelter.

Either way, the share of renters paying more than 30 per cent is significant, said Nathanael Lauster, a UBC professor and the author of The Death and Life of the Single-Family House: Lessons from Vancouver on Building a Livable City.

“When it comes to renters in particular, it’s pretty clear that this is a real problem of people not being able to find affordable rental housing,” he told Global News.

Lauster had a few questions about why the CMHC considers 30 per cent as the benchmark for what’s considered “affordable” shelter.

“It is to some extent an arbitrary number,” he said.

READ MORE: Vision Vancouver says it heard people ‘loud and clear’ on housing, but some are skeptical

Nevertheless, he said we “want to make sure people have enough left over.”

“If it’s a world where people are just choosing to spend a little more on rent because they want a really nice place, and other people choose to spend their money differently, that’s not such a bad world,” Lauster said.

“But if they have no choice, which is I think the world we’re in, that’s a real problem.”

Lauster said the sheer number of people putting more than 30 per cent of their income toward shelter across the Vancouver CMA suggests that housing should be treated as a Metro Vancouver issue, rather than a “City of Vancouver” issue.

Yan “absolutely” agreed — but he also said that affordability metrics looking only at the share of income spent on rent don’t capture the whole picture.

“What we’re missing is transportation costs,” he told Global News.

Yan noted that the region isn’t just facing an “affordability” problem; it’s facing an “availability” problem, in which people are having to look for places to rent outside of Vancouver’s urban core.

“As a consequence, that inherently means if your job is in the urban core, right, that it used to be, ‘Hey, I’ll hop on a bus in East Van or I’ll walk over from the West End,'” he said.

Now, people have to look to communities like Burnaby or Langley.

“It might work for certain people,” he said. “But for others, you know, when you don’t live near a public transit line, that means your transportation costs, both in physical, actual costs, but also opportunity costs will suddenly go up.

“The idea of being under pressure for rent is now being under pressure for transportation.”

Yan noted that the nearly 45 per cent of City of Vancouver renters who put more than 30 per cent of their income toward shelter might be better off than someone in Pitt Meadows, where the share is 35 per cent.

“If you’re living in Vancouver, you’re taking the bus or biking,” he said. “But if you live in Pitt Meadows, you’re probably not, so you can see the cost.”

But how to solve the issue of high rents — and transportation costs?

Yan said governments all over the region might want to think about zoning for particular forms of housing around certain areas, like on lots close to transit.

“I think particularly around SkyTrain routes, there’s a fair discussion that since renters take transit more often than owners, that there should be a consideration of tenure for higher-density developments along transit routes,” he said.

Yan said such measures are about realizing that renting is a part of living in Vancouver, “for a lifetime.”

“That isn’t some temporary phase of being on the route to home ownership,” he said.

- 35 court dates and no trial: Family of B.C. double homicide victims frustrated by delays

- ‘Embarrassing’: Vancouver councillor calls out mayor over drugs comment controversy

- ‘Like a spelling mistake’: B.C. teen’s DNA ‘corrected’ to cure rare disease

- ‘Ghosted’: Canadians stranded in Puerto Vallarta say they are abandoned by WestJet

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.