How many newcomers should Canada let in next year? We’re about to find out. Ottawa is set to announce the country’s 2018 immigration target by Nov. 1.

The federal government has already upped Canada’s immigrant intake to 300,000 annually, but could it – and should it – go even further?

That’s the question at the heart of a new report by the Conference Board of Canada, which forecasts the potential impacts of different immigration levels on the overall economy, income levels and public spending.

The findings might be disappointing for both supporters and critics of immigration. The pitch for higher immigration levels is simple: More people means more workers to fill up vacancies, entrepreneurs to create new jobs, and customers to buy things like cars and homes. Plus, immigrants are on average younger than native-born Canadians, so newcomers are – quite literally – an injection of fresh blood that helps pay for the ballooning expense of supporting our aging population.

READ MORE: Pro- and anti-immigration protesters face off in duelling rallies near Lacolle border

The popular case against immigration is, perhaps, even simpler: Immigrants compete with native-born workers for the same jobs, tend to drive down wages, and weigh on the public social safety net.

Most economists would say the truth is somewhere in the middle: Over the long term, immigration doesn’t seem to have significant effects on either jobs or wages.

The results of the Conference Board of Canada survey are somewhat in the middle as well.

WATCH: Border officials brace for another spike in asylum seekers crossing into Canada

What would happen with a target of 450,000 immigrants?

The authors look at several scenarios. At one end of the spectrum is the future Canada faces if it leaves the immigration target as is. That means letting in roughly 0.8 per cent of its population as newcomers every year. At the other end, is the prospect of ramping up the target to let in 450,000 immigrants per year by 2025, which would be about 1.1 per cent of its population, and leaving that proportion constant until 2040.

The 450,000 number comes from the federal government’s Advisory Council on Economic Growth, which actually recommended aiming for that immigration level by 2021. The authors of the report, however, decided to “delay the increase by four years given the low probability that the federal government would have the operational capacity to ramp up immigration that quickly.”

READ MORE: Canada’s immigration system discriminates against children with disabilities, say families

- As Canada’s tax deadline nears, what happens if you don’t file your return?

- Do you need to own a home to be wealthy in Canada? How renters can get ahead

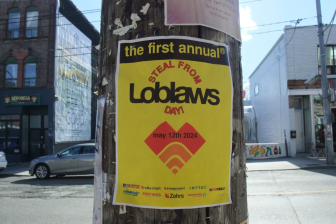

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- Investing tax refunds is low priority for Canadians amid high cost of living: poll

The study finds that maintaining the status quo would result in a slower economy, with real GDP growth averaging 1.85 per cent a year (by comparison, some expect Canada to blow past three per cent growth this year). Health-care costs as a share of provincial revenues would swell to over 42 per cent, up from 35 per cent today.

Under the 450,000-by-2025 scenario, Canada would be accepting 528,000 people a year by 2040. Economic growth would average just over two per cent a year, and health-care spending as a share of provincial revenues would hover around 40 per cent.

READ MORE: Canada rejects hundreds of immigrants based on incomplete data, Global News investigation finds

The flip side is that GDP per capita would be slightly lower in the high-immigration scenario, at $61,600 per person compared to $62,900 under the status-quo scenario. That’s mainly because immigrants tend to earn less than native-born Canadians, making just over 83 per cent of Canada’s average wage.

It is the lower income of immigrants, not lower earnings for Canadians, that drags down the per capita GDP figure in the high-immigration scenarios, the authors note.

But half a million newcomers a year would also result in “higher social expenditures,” reads the report. The authors do not wade into how that additional public spending would compare to immigrants’ contribution to lowering fiscal pressures from health-care costs.

WATCH: How the feds plan to house asylum seekers entering Canada as winter approaches

The numbers alone aren’t exactly a crystal-clear case for lifting Canada’s immigration target to 450,000 and then over 500,000. But the authors argue Canada could squeeze more growth out of its newcomers if it did a better job of helping them find professions that match their skills and education. If, say, Pakistani doctors managed to work as doctors here in Canada, instead of shuttling people around in cabs, we would all benefit. And we could perhaps stave off that projected dip in per capita GDP.

Overall, though, the study also highlights just how tiny even the numbers 450,000 and 500,000 look like when compared to the magnitude of the economic and fiscal challenges that face Canada as the baby boomers march into retirement.

READ MORE: Immigration lawyer in disbelief and disappointed in inaccurate immigration information

Canada would need to add six million people just to fill up the demographic gap left behind by boomers, economist Stephen Gordon noted a few years ago. And that hole keeps growing by 200,000 per year.

Boosting immigration levels to 450,000 people a year and even higher would likely help boost growth. It might even alleviate fiscal pressures. But it won’t come close to cancelling out the impact of an aging population and low birth rate.

Comments