Vaughan resident Furio Liberatore went home in the spring of 2015 and was greeted by an ominous sight: a sign on the lot behind his house.

“I came home and saw a sign for a massive development,” he said. “I was devastated.”

The 11-acre field behind his house — 230 Grand Trunk — is a haven for wildlife. “You see deer, coyote, frogs. You hear the trees rustling. It is very peaceful.”

Liberatore, a plumber and father of two, said he paid a premium for his house because of the nearby field. “City officials told us that it’s protected land and nothing can be built on it.”

Those bureaucrats weren’t lying. On paper at least, this land should have been very hard to develop. There were endangered species like butternut trees in the area, as well as significant species like green frogs and bullfrogs.

It was also part of Ontario’s Greenbelt: almost two million acres of land meant to permanently protect important natural heritage and agricultural areas from urban sprawl. Some areas of the Greenbelt have even stronger levels of protection. Around the Greater Toronto Area, the Greenbelt protects forests, rivers and farmland. Along with municipal rules, it’s supposed to keep suburbs like Vaughan and Brampton from growing out of control.

But, developers want that land. As part of a 10-year review process, the province is currently looking at more than 600 requests to remove land from the Greenbelt Area, according to research by the Greenbelt Foundation, an environmental group.

Zoning can be changed and formerly-protected land can be bulldozed. And critics say the protected green space could potentially be developed all over the province, if land-hungry developers are allowed to chip away at the Greenbelt.

Here’s one example of how that happened in the past.

The history of 230 Grand Trunk

The original landowner, Eugene Iacobelli, owned what was once a mostly picturesque wooded lot with a small stream running through it near Grand Trunk Avenue.

The land was part of the Greenbelt, and even had additional protections from the City of Vaughan, “completely protected with environmental and open space designations,” according to one government document.

But Iacobelli was determined to develop. He tried through much of the 2000s, but the city fought his development plans at the Ontario Municipal Board — the provincial body that arbitrates land disputes — and won the initial fights to preserve the land.

Iacobelli then took matters into his own hands. He illegally cleared part of the land himself, driving a bulldozer and knocking down trees.

“He was charged by York Region for cutting those trees,” said Sandra Racco, the Vaughan city councillor who represents the ward. Racco said the city even tried to buy the land from Iacobelli “to keep it as an open piece of land for park users.”

Get breaking National news

The Iacobelli family sold the land in 2015 to another developer, Dufferin Vistas Ltd.

It was then that the city dramatically changed its position behind closed doors. Suddenly, it supported developing the property.

Documents obtained by Global News show that Vaughan city council approved a secret deal to develop the land with the new owner in June 2015.

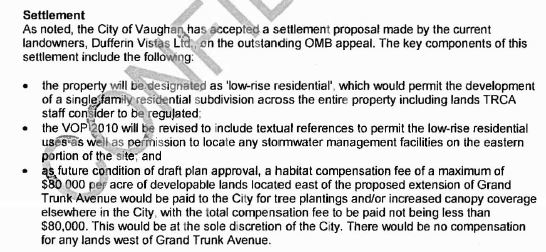

The Toronto Regional Conservation Authority, a government body that advises municipalities on what lands should be protected to prevent flooding, preserve water quality and natural habitats, described the deal in internal documents this way:

The settlement also included a maximum fee of $80,000 per acre for developable lands east of Grand Trunk Avenue, for “habitat compensation.”

Read the full TRCA document here

Because the decision was made behind closed doors, it’s not known why the city changed its mind. “The whole matter was discussed in closed session,” said Vaughan deputy mayor Michael Di Biase. “It is confidential information.” He referred Global News to the city’s legal department.

But critics say Di Biase has a conflict of interest because he is both Deputy Mayor of Vaughan, the city that wanted to develop the land, and vice chair of the TRCA, the agency charged with protecting it.

Global News has learned that Di Biase tried to pull the TRCA from making its case to protect the land before the Ontario Municipal Board, which was deciding whether the land should be developed. Di Biase helped lead the TRCA at the time.

“It’s like the fox is in charge of the henhouse,” says city councillor Maria Augimieri, about Di Biase. Augimieri is an environmental advocate and the chair of the board of the TRCA.

“It is irresponsible for developers and public representatives to gobble up environmentally sensitive lands,” she said. “These people are champing at the bit to make a quick buck and disappear.”

Di Biase says he was only doing the City of Vaughan’s bidding. Vaughan city lawyers wanted their city and TRCA to have a “common front” and present a united position before the OMB.

The TRCA Board ultimately rejected Di Biase’s attempt to withdraw the agency from the case and continued to make its case at the OMB.

The OMB’s decision was “based on what the city had to say, what the TRCA had to say and what the developer’s consultant had to say,” said Di Biase.

And the OMB`s decision was a compromise: only part of the land would be developed.

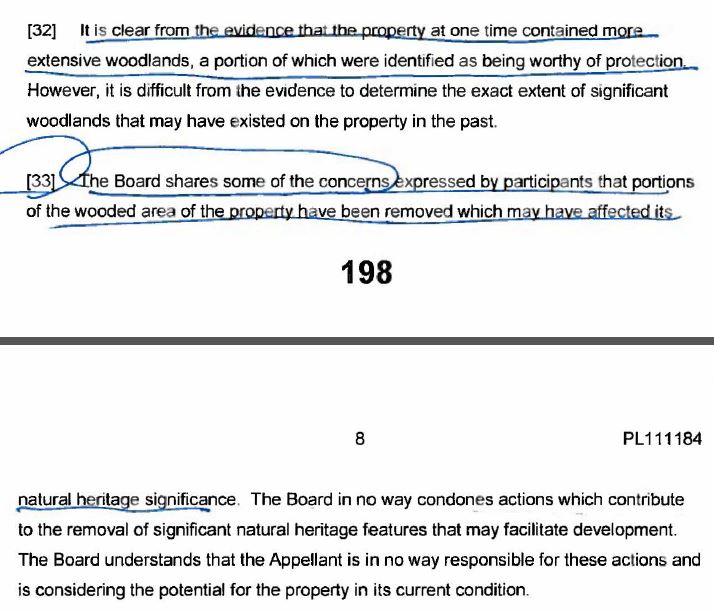

The eastern edge of the property where a wetland sits would be preserved. The middle chunk behind Liberatore’s house would be studied further, while a third tranche on the western edge could be developed – partly because there were no trees on it anymore. The original landowner, Iacobelli, had cut them down years before. The OMB decided that part of the land would therefore not be subject to the same stringent protections.

It said it did not condone the removal of “natural heritage features,” rather it made its decision based on the “features of the site as they exist” and approved rezoning part of the land.

Read the full OMB decision here

It’s as if the old developer was “rewarded for cutting down a woodlot,” said Glenn De Baeremaeker, a member of the TRCA who did not approve of the decision.

Cam Milani, the developer, told Global News that the 230 Grand Trunk development “conforms to the Vaughan Official Plan.”

“We will continue to work with the City and the community to ensure the best possible development for Vaughan.”

Today, nature still dominates the land, with trees and shrubs that are coming back, and a young forest in full growth. But a large sign indicates that development is imminent.

Closed-door meetings

Vaughan’s original decision on the Grand Trunk land — which helped set things in motion, was made behind closed doors, with limited public oversight or knowledge of what exactly was said. De Baeremaker doesn’t think that should be the case.

“When things are done in secret and behind closed doors, the environment usually loses and this is a very good case of that,” said De Baeremaeker.

Liberatore has been following the back-and-forth at city hall over the land closely. In a recent vote, held in public, the TRCA board unanimously decided to ask the City of Vaughan to consider purchasing the 230 Grand Trunk land for protection. Liberatore said third-party oversight from agencies like the TRCA is crucial in cases like his.

“If it wasn’t for the TRCA, there would be an 80-foot ravine filled in with 106 town homes built on environmentally-sensitive lands,” he said.

In the meantime, the developer is taking the case back to the OMB, meaning that many of the upcoming municipal discussions could also be held behind closed doors.

The City of Vaughan is looking for more control over development too – examining whether the TRCA should have a more limited role in the city’s official plan.

Generally, cities consult with the TRCA when they draw up their official plans to make sure they are complying with provincial policies and they are not paving over or developing environmentally-sensitive lands or waterways.

For De Baeremaeker, this further chips away at environmental protections. “The environment will be shortchanged.”

Comments