Jim White has six scars – three on each shoulder – left over from his time at a residential school in the early 1950s.

He’s not sure what they are, though he remembers how he got them.

“The nurse came and basically opened up my shoulder in three places,” he said. “I remember that it was painful. I remember that it looked like an incision and then they applied the stuff with what looked like gauze, and a clear fluid was pushed into these openings. And then a gauze put over and then it was taped shut.”

He was told to report back to the nurse the next week to have the bandage changed. “By the time the week arrived to see the nurse, the smell that came off this was just, it was horrendous. It smelled like rotten food, is what it smelled like. And it went on until these openings closed up which took about a month or two.”

He was told nothing about why he was cut as a young child, he said.

“And I still live today with the nagging question: what in the world did they do?”

After reading reports about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, he suspects he might have been part of an experiment, performed on children at his residential school in Port Alberni, B.C.

READ MORE: Residential schools subjected students to disease, abuse, experiments – TRC report

The 73-year old grandfather from Abbotsford contacted Global News to see if we could help.

While we couldn’t find out anything for certain, here’s what we learned about vaccination and experimentation at Canada’s residential schools.

Vaccination and scarification

David Scheifele, director of the Vaccine Evaluation Centre in Vancouver, thinks that what White is describing sounds like an earlier form of smallpox vaccination, still being performed in the early 1950s.

“The liquid vaccine containing the vaccine virus had to be introduced into the skin to create a local infection that stimulated immunity. The methods of doing this varied but “scarification” was common and matched what this person described,” he wrote.

“Several scratches were made in the skin deep enough to bleed. A drop of vaccine was applied to each scratch, then the area was covered with a bandage. Local sores resulted from a successful “take”, that would later form permanent scars as proof of protection. Several inoculation scratches were needed to achieve a good success rate.”

These scratches were usually done in groups of three, he said, and while it would be unusual to do both arms, it might have been done if the vaccinator wasn’t likely to return. Smallpox vaccinations were done with needles beginning in the late 1950s, he said, and many older Canadian adults would have dime-sized scars from that newer procedure.

Smallpox vaccination is just a guess though: White wasn’t told anything about what was happening, and Scheifele hasn’t examined him.

What Scheifele describes sounds right to White though. “It describes what happened,” he said. “It resonated with my memory.”

Milk and flour

But, White had good reason to suspect he was being experimented on – though it has nothing to do with his scars.

Based on his attendance at the Alberni residential school in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he was almost certainly part of a nutrition experiment being done on all kids at that school, according to Ian Mosby, a post-doctoral fellow in history at McMaster University.

Get daily National news

He’s not the only one – Mosby has unearthed documents describing nutrition studies performed on just under 1,000 indigenous children at residential schools across Canada from 1942-1952.

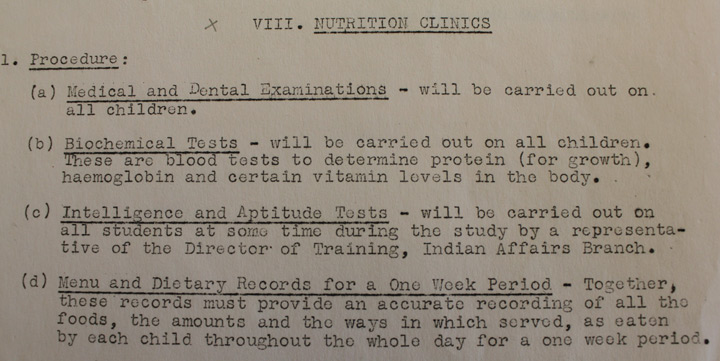

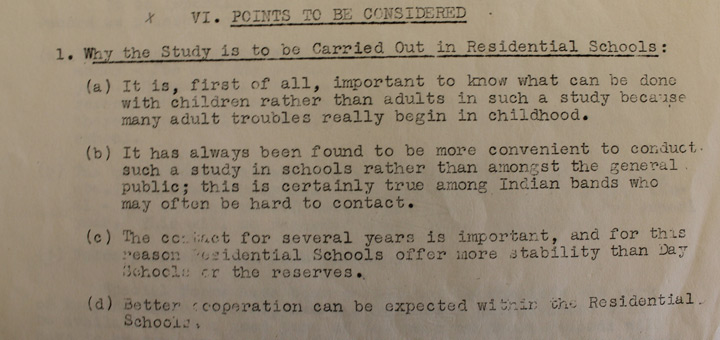

These experiments were designed to test the effects of dietary interventions on malnourished children — as so many who attended a residential school were.

At some schools, students were given vitamin-enriched flour (not yet legal in Canada). At others, vitamin supplements. At White’s school, Alberni, the milk ration was tripled to see whether it had any noticeable effect on the low vitamin levels of students at the school. Students had occasional blood tests and medical examinations to test this.

Residential school students were chosen to be test subjects for many reasons, said Mosby. They were wards of the state, and as such, the government had control over much of their lives — and their parents didn’t.

Not only that, the fact that they were already malnourished made them good candidates for nutritional research, he said. And, these were children who weren’t white, he said, “So that made them ideal subjects to a certain extent from the perspective of these scientists.”

There’s no evidence that researchers ever tried to get parental consent for these tests, he said.

It’s not that consent just wasn’t done for experiments at the time: Researchers did get consent for another similar school trial a few years earlier in 1947 — testing the effectiveness of free school lunches on children’s health in Toronto’s Moss Park neighbourhood — but in that case, the students weren’t indigenous.

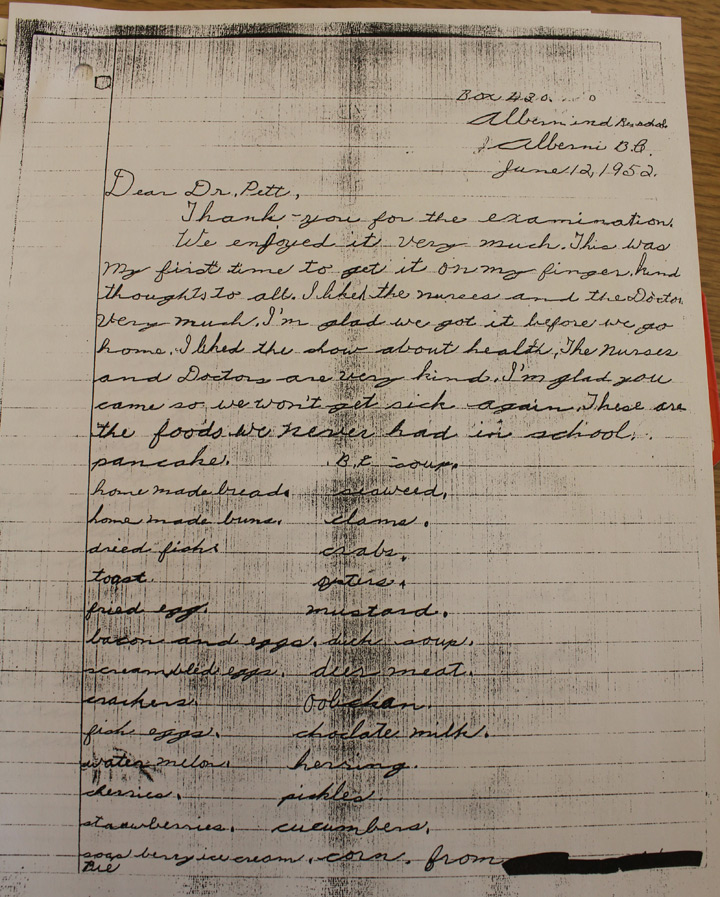

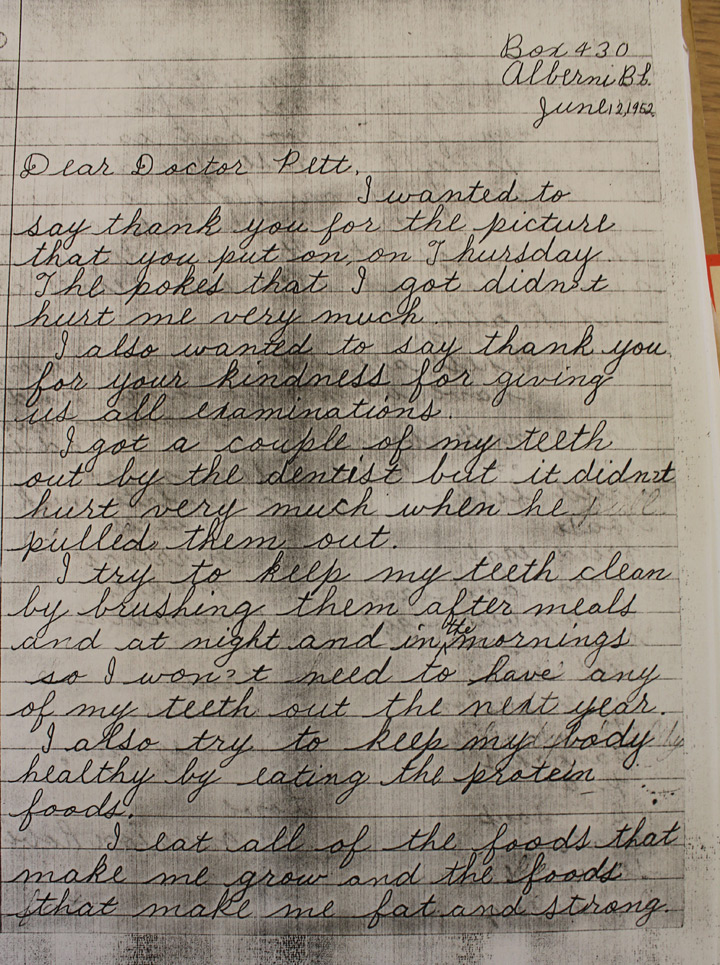

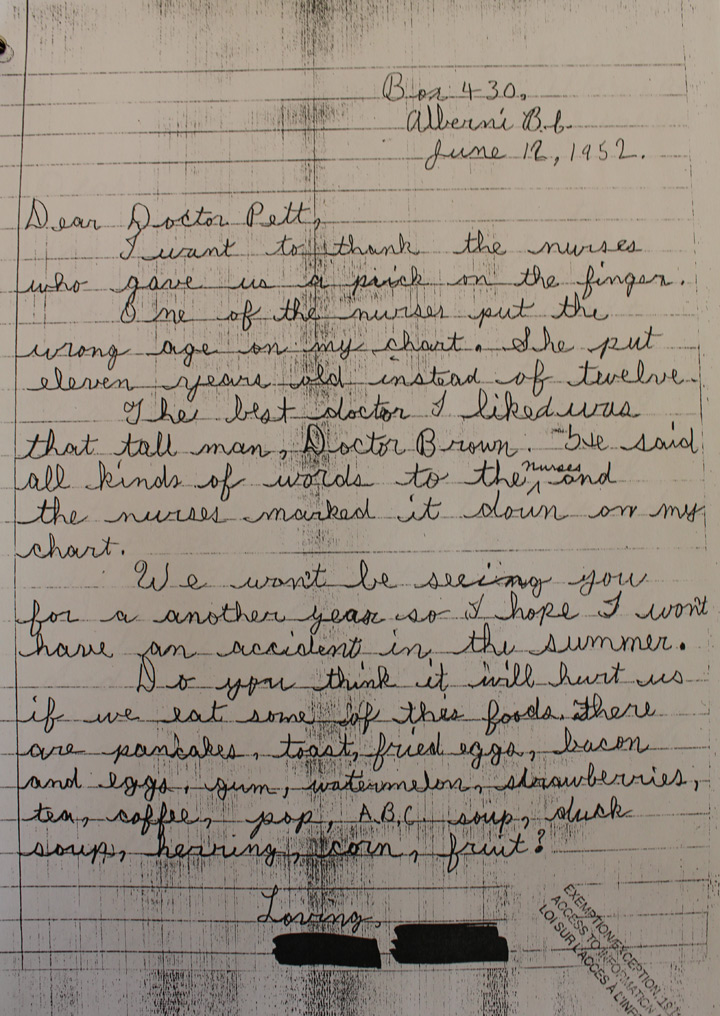

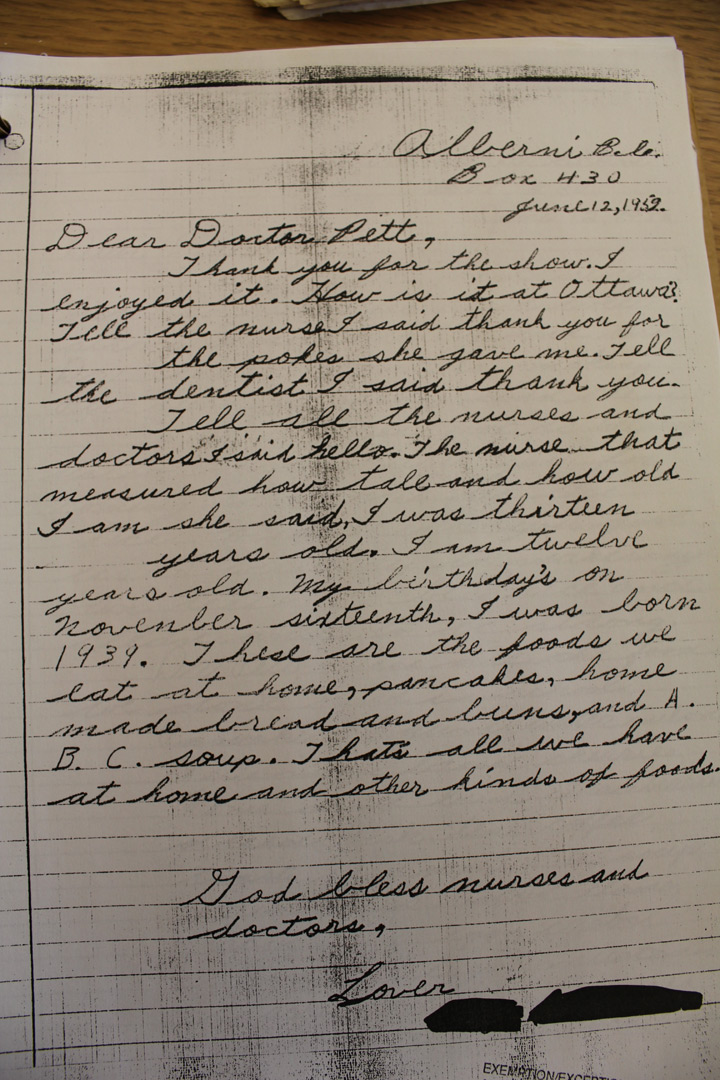

Children at the Alberni school wrote to the lead researcher in 1952. He was interested in what the kids ate at home, said Mosby, so he got a teacher to get students to tell him in a class exercise.

These letters are still in a box at Library and Archives Canada. They’re all written in nearly the same way: thanking the nurses for the “pricks” they gave them, promising to eat well, and listing off all the foods that they’re looking forward to eating when they get home.

“They’re pretty haunting letters,” said Mosby.

Gallery: Alberni students’ letters to researchers

For the most part, the nutritional changes didn’t cause the students direct harm, though at a school in Kenora, many students began to develop iron deficiency after being fed an enriched flour mix that included bone meal.

And, said Mosby, “The experiments basically took advantage of the fact that the children were already being fed inadequate diets. That’s the real harm, it’s not so much the experiments themselves, it’s the conditions in the schools that made the experiments possible.”

Testing TB vaccine

Indigenous children were also used to test a tuberculosis vaccine, according to research by Maureen Lux, an associate history professor at Brock University.

The BCG vaccine, which is still used today, was regarded with some suspicion in the 1930s, she said. Although it was being used in Quebec, tuberculosis experts in English Canada saw it as an inferior or ineffective way to treat the disease, compared with treatment at sanatoriums or hospitals.

But one sanatorium operator in southern Saskatchewan decided to test the vaccine on the local indigenous population.

“They were seen as a population literally soaked with tuberculosis,” said Lux. “They were seen as a population that would infect the surrounding non-Aboriginal population.”

And, if it worked, a vaccine was a cheaper way to prevent tuberculosis than addressing the real problems, like poverty, nutrition and the standard of living in those communities.

Roughly 600 infants took part in the trial, she said, and unfortunately, many died – though not from tuberculosis. “About 20 per cent on both the vaccinated side and the control side actually dropped out of the trial because they died before their first birthday – not from tuberculosis, from exposure and malnutrition and other diseases.”

“So the clear takeaway was TB wasn’t the greatest threat to this population, poverty was.”

Again, parents didn’t consent for their children to take part in the trial. When the lead researcher wanted to vaccinate non-indigenous children, he got consent, she said, but he didn’t bother with indigenous kids.

Indian Health Services seemed satisfied enough with the trial’s results, and used the vaccine across Canada after 1945, said Lux.

A ‘jerry-built’ solution

But some health care workers got inventive. For safety reasons, people who had already been infected with TB couldn’t be vaccinated. So, they were first tested, and if they were clean, they could get the shot.

But the test took too long for some: two or three days to show a result. “They saw this as a waste of time and money,” said Lux.

So, one researcher came up with a solution: dilute the vaccine, and scratch it onto people’s skin as a test, giving an instant result. It was a “jerry-built solution”, said Lux, but she believes it was used all across Canada.

“It did actually result in people becoming quite ill and developing tuberculosis in some cases,” she said. “But that was kept from public discussion of course.”

She found records of two young girls developing tuberculosis in their lymph nodes, something that one researcher thought was an interesting enough finding to have published in a medical journal – though that idea was quickly shot down by the deputy minister of health.

This procedure was used up until at least 1966, she said.

More experiments?

- Here’s what we know about the Tumbler Ridge mass shooting investigation

- B.C. 2026 budget ‘neither’ big cuts nor tax increase, minister says

- Former Conservative leader John Rustad says he’s not running for his old job

- Parts of B.C.’s South Coast set to see snow-rain mix with ‘rapidly changing’ travel conditions

There may have been more experiments done on indigenous people, said Lux, though she hasn’t found records of many. “Experiments, if they’re going to be any good, need clear record-keeping,” she said. A lot of records were destroyed by Indian Health Services – though she doesn’t know why.

“The stories from survivors are of potentially other experiments that we don’t know about,” said Mosby. “I think it’s really worth listening to a survivor and asking them what they think happened to them because there’s a lot of troubling stories that are difficult to get answers to.”

As for Jim White, he took the news that he was likely part of a nutrition experiment with equanimity.

“At some point in my life, I decided, made a choice for myself that I would not allow the rage to get any worse than what it is,” he said. “And I think that’s why so many people commit suicide. That’s why a lot of them decide to remain as alcoholics, remain as drug addicts, remain as prostitutes is because they’ve allowed the rage and the madness to overflow. They’ve allowed too much of it to dictate who they are as a human being. And I’ve never ever allowed that to happen.”

“I have just chosen, a long time ago, that whatever they find, they find.”

Although he wants to know more about what happened at his school, he’s accepted he might never know for sure.

“Yes they may have done all these experiments, yes they may have removed whatever vitamins from our food. But I’m grateful that I’m here despite that, despite what they did. I’m an Aboriginal man making a contribution to society, who has had a number of high points in his life and is successful at a lot of things – that I shouldn’t have been successful at given what I’ve gone through in the residential school system.”

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.