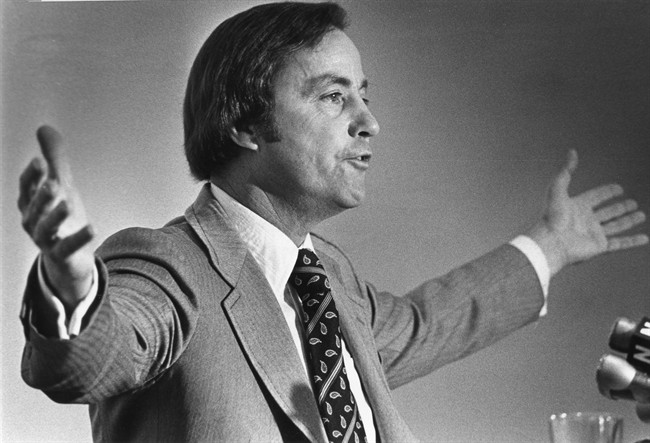

Former B.C. Premier Bill Bennett, who died Thursday, has deservedly been remembered by many as a “builder” and a “visionary” who left a personal stamp etched on this province that will never disappear.

But it is also important to remember that he presided over B.C. during one of the most turbulent periods of its history, and that lessons learned from that experience reverberate to this day. As well, it was at that time that his legendary toughness came to the fore.

I had a unique front row seat (of sorts) on the events of those times. More on that in moment.

It’s easy to see the “building” aspect of Bennett’s legacy, as examples of it are seemingly everywhere: the SkyTrain system, B.C. Place stadium, Canada Place, the Coquihalla Highway, the Alex Fraser Bridge, the list is long. Even the development on the lands around False Creek can be traced to his determination to bring Expo 86 to Vancouver in 1986.

What’s more difficult to “see” about Bennett’s reign can now only be viewed through archival news footage, visits to the library (or Google) or from personal experience.

I’m referring to the crazy, tense, wild rollercoaster ride this province was on from the May, 1983 election to mid-November of that year. The province careened from controversy to mass protest (and staunch determination by Bennett and his government) to work stoppages to nearly (so some think) a complete general strike.

WATCH: Keith Baldrey on Bennett’s passing

Bennett’s fiscal restraint program, which he first unveiled a year earlier with his wage controls for public sector employees, was expanded with his government’s first post-election budget in July. That budget included 26 bills that undermined collective bargaining in the public sector, cut social services and dismantled offices that protected tenants and minorities.

The budget unleashed an unprecedented wave of protest, which quickly evolved into two organized and allied groups: organized labour’s Operation Solidarity and the community activist driven Solidarity Coalition.

Get daily National news

There was an uneasy tension between the two groups almost from the start, as they tried to figure out how to take on the Social Credit government. Operation Solidarity was run by veteran union organizers who were more rooted in reality than their counterparts in the Solidarity Coalition, many of whom demonstrated earnest idealism and ideology that had little in common with the “workers” on the union side.

Local author Stan Persky came up with the idea that the “movement” should publish a weekly newspaper. Operation Solidarity agreed to fund such a venture (the paper was called “The Solidarity Times”) and Persky turned to a group of unemployed, youthful Vancouver journalists just starting out in their careers to staff the thing.

READ MORE: Bill Bennett, B.C. premier from 1975 to 1986, dead at 83

I was one of them, and became the paper’s assignment editor and one of its reporters. So began almost three months of no sleep, too much coffee and an often exhilarating experience that I knew was not going to last long.

In fact, while so many people got caught up in the whole protest “scene” and whipped each other into an emotional frenzy about somehow overthrowing a government none of them had ever supported in the first place, it quickly became apparent to myself and my colleagues that no such scenario would occur.

I covered that year’s Social Credit convention at the Hotel Vancouver (where 60,000 people marched in protest in a circle around the hotel) that fall for the fledgling paper and found no evidence of any panic or even much concern among the delegates or the elected politicians.

Almost as a lark, I assigned a reporter to quiz NDP MLAs on what they thought about a general strike, the idea for which seemed to be gaining a certain kind of momentum among the more left-wing parts of the Solidarity movement.

What happened next was very telling.

WATCH: Politicians and reporters remember Bill Bennett

The NDP MLAs, to a person, loudly and vociferously rejected such an avenue of action, which was what I had expected (the party would hardly want to have Opposition to the government morph into an extra-parliamentary version it had no control over).

We were laying out the paper that week (using typesetters and actually putting copy on the page) and word got to the Solidarity executive that a story was about to go out that said a general strike was a dumb and essentially pointless exercise.

The next thing I knew, I was summonsed to a conference phone call with much of the executive — union leaders and community ones as well — and was told such a story would cause enormous grief to the “movement” and could I please pull it?

Upon hearing this, our entire staff (who considered themselves independent journalists) threatened to quit right there, and the unionized printers laying out the paper also threatened to walk off the job. Quite the little crisis!

A compromise was reached (the story was watered down, but still ran buried inside) and everyone calmed down.

But that phone call (with its air of frantic tension) told me right there the jig was up, as I had suspected almost from the start. There was simply no way that organized labour, community activists and the NDP could hold together as a coalition when things got “real” and were not about shouting protest slogans anymore.

The union leaders realized they could not allow the “romance” of a general strike to dictate their strategy, and they knew Bennett had more weapons than they did should things ever get that far.

Accordingly, a few weeks later, forestry union chief Jack Munro flew to Bennett’s Kelowna home and signed a deal to get off the roller coaster. The Solidarity Coalition was livid, but by then no one with any real power (i.e. organized labor) really cared about it anymore.

Interestingly, the protest movement had to go to Bennett’s turf to get off the cliff, and not the other way around. His legendary toughness, which got him re-elected in May, stood firm right through the crisis to the meeting in his living room in mid-November.

Yes, Bill Bennett was a visionary builder. But he could also be a hell of a tough opponent, as his political enemies found out time and time again.

Keith Baldrey is chief political reporter for Global BC

Comments