Mary arrived at the clinic with an envelope of cash.

She’d scraped together the $700 cost of her abortion from her own savings and a loan from her aunt, who accompanied her.

She was calm by then. Surprising, perhaps, given that 12 hours earlier she’d found a rosary and bloody photos of fetal remains in a bag left hanging on the doorknob of her home.

Inside the bag were letters, apparently from adopted children, “saying I shouldn’t do what I’m doing, I’m killing a life, this child deserves a family,” Mary recalls.

“Even though my mind was made up, it hurt. I cried a lot. …

“Why would someone come to my door? It’s a breach of my privacy.”

And of her trust: Mary had confided in few enough people to know exactly who’d told anti-abortion activists about her appointment. That knowledge chilled her.

“I’ve never felt so betrayed in my life.”

That ordeal’s not abnormal. For thousands of Canadian women that’s what it’s like getting an abortion in the 21st century.

In the wake of a fatal mass shooting at a Colorado clinic, as a new government takes the reins and as a new abortion pill rolls out next year, Global News took a closer look at who gets access to abortions — and who doesn’t.

About 100,000 Canadians need abortions every year — arguably more, but we aren’t sure because our national statistics are unreliable. That means that over the course of a 45-year reproductive lifetime, more than 4.5 million women in this country will terminate unwanted pregnancies.

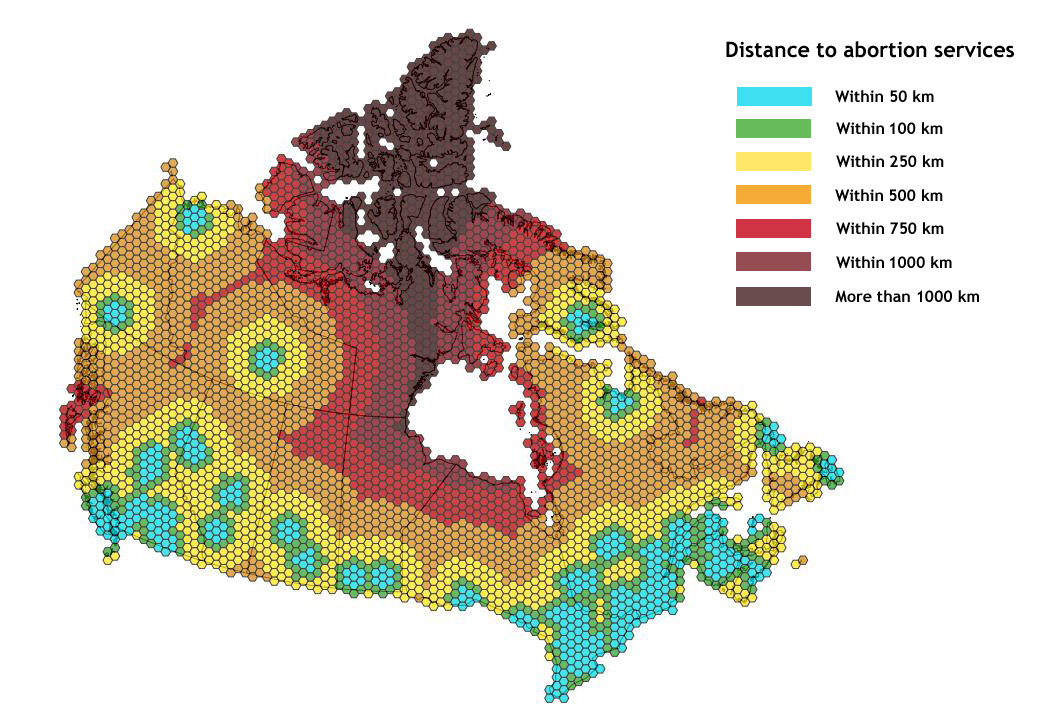

But if you’re in Canada and you need an abortion your chances of getting one — and the distance you’ll travel, the amount you’ll pay, the number of medical professionals whose approval you’ll need and the degree of pushback you’ll get from people judging your decision — vary widely depending on where you live.

READ MORE: Where can you get an abortion? It’s a secret

Provider patchwork: How abortion access varies across Canada

How the ‘abortion pill’ Mifegymiso could change reproductive health

Mary didn’t tell her parents she’d gotten pregnant and paid out of pocket to terminate the pregnancy and was greeted at her door by a gruesome warning the night before.

She still hasn’t told them. Mary isn’t her real name: Four years later, she still isn’t comfortable talking publicly about her experience.

Not because she’s ashamed. Mary knew at the time — twentysomething, unexpectedly pregnant and on her own — it was the right call.

“I’m still not ready to be a mom. And I’d have no problem doing it again.”

That said, “it’s not an easy decision.” The New Brunswick native had to choose between an eight-week wait-list for a hospital abortion or paying for one herself at a clinic. She couldn’t afford to wait. She knows she’s lucky she had the cash and support she needed.

“It should be funded. Because s–t happens,” she said.

“A 13-year-old girl? She doesn’t have $700.”

Fewer than one in six Canadian hospitals provide abortions. The vast majority of them are in urban areas, within about 150 kilometres of the U.S. border.

Map by Leslie Young, created using location data from Action Canada for Sexual Health and Rights. For more on why we can’t publish exact location details, click here.

And the poorer or younger you are, the more remote your home, the shakier your safety net or the more urgent your need, the harder abortions are to get.

Canada’s newly minted health minister Jane Philpott is under pressure to expand abortion access in Canada.

She admits access is “patchy” but declines to give details as to how she’ll fix it, or how she’ll approach the rollout of new abortion pill Mifegymiso, which becomes available in Canada early next year.

Reproductive rights have proven more intractable than other social and equality issues, says Joyce Arthur, head of the Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada.

“There are these deep-seated fears and anxieties and uneasiness around these issues of women’s sexuality, but also around motherhood,” she said.

“It’s hard to overcome that. … We revere motherhood but at the same time, we don’t support mothers.”

‘People don’t really think that abortion is an issue’

It’s been almost three decades since crusading abortion-provider Henry Morgentaler’s Supreme Court victory. Many Canadians assume the issue is settled: Women in this country have autonomy over their bodies and a right to abortions, period.

It’s nowhere near that simple, as Rachael Johnstone and Emmett Macfarlane explain in a paper published this fall in the International Journal of Canadian Studies.

“Many people don’t really think that abortion is an issue in Canada any more,” Johnstone said.

But “the 1988 decision created a patchwork of access that in many ways looked like Canada before 1988,” she said.

“The main reason [the old law] was struck down was unequal levels of access. And we have unequal levels of access now.”

The 1988 Supreme Court decision was extremely narrow. It viewed abortion as something governments weren’t allowed to actively prevent you from accessing, not something governments had an obligation to make accessible.

The seemingly minor distinction is an important one: When a court affirms a person’s negative right it means protection from government infringement on that right; a positive right, on the other hand, is about your right to something the government provides.

It means the bar for a judge wanting to remedy persistent inequitable access is significantly higher.

“Now most of [the unequal access] is caused by government inaction. And that’s a big hurdle for judges to get over,” Macfarlane said.

When abortion restrictions in New Brunswick and PEI made national news last year, many people in other provinces were shocked, Johnstone notes.

“People were saying, ‘Is this really a policy in Canada? We didn’t know.'”

In January New Brunswick struck down its requirement for two doctors to sign off on a woman’s abortion. Macfarlane considers the decision a victory for the pro-choice movement — even if restrictions on where a woman can get an abortion and what the government will pay for remain in place.

“That was the most egregious actual governance rule surrounding access in the country,” he said.

It “was blatantly unconstitutional and now it’s gone. Finally.”

‘If [abortion is] a personal choice, why are taxpayers paying for it?’

Canada’s next reproductive rights revolution probably won’t come from the courts.

“Litigation is really expensive and it’s very slow,” Macfarlane said.

That would leave things up to provincial and federal governments and anyone putting public pressure on them.

Pro-choice public pressure can be tough to come by if most Canadians — those in the urban centres of Ontario, B.C. and Quebec, especially — think the issue is moot.

“People just assume that everything is fine. But of course it’s not,” Arthur said.

Those who’d rather see Canada crack down on abortion are at least as vocal as pro-choice groups, if not more so. Marches for Life in Ottawa and a recent anti-Liberal, anti-abortion campaign in Saskatoon indicated as much.

- Peel police chief met Sri Lankan officer a court says ‘participated’ in torture

- Budget 2024 failed to spark ‘political reboot’ for Liberals, polling suggests

- Wrong remains sent to ‘exhausted’ Canadian family after death on Cuba vacation

- Liberals having ‘very good’ budget talks with NDP, says Freeland

Last month anti-abortion activists rallied in front of PEI’s legislature, calling on the provincial government to “keep Prince Edward Island abortion-free.”

They presented a petition to that effect with more than 3,000 signatures to pro-life MLA James Aylward, says Sarah MacDonald, youth representative for Campaign Life Coalition PEI.

“We’re just trying to raise our voices and let the government know a lot of islanders don’t want an abortion clinic on the island,” she said.

MacDonald wants measures many equality advocates would agree with: subsidized child care; support for single mothers; better ante-natal and neo-natal care.

But abortions, she said, aren’t among those “life-affirming” choices. She doesn’t want tax dollars funding them under any circumstance.

“If [abortion is] a personal choice, then why are taxpayers paying for it?” she said.

“I think when you consent to having sex you’re consenting to the idea, or the possibility, that you’re going to be having a baby.”

The tricky definition of medical necessity

Health care is a provincial issue — for the most part it’s up to the provincial governments to decide what services are covered and how you get them.

But the feds have some leverage: Ottawa’s allowed to withhold health transfers from provinces if it thinks they aren’t holding up their end of the Health Act.

Pro-choice advocates argue uneven abortion access violates the Health Act’s principle of universality.

But that argument hinges on abortion being a “medically necessary” health service under the act.

Is abortion medically necessary? Depends whom you ask.

“The Canada Health Act talks about medically necessary services without defining what ‘medically necessary’ is,” said Wilfrid Laurier University health economist Logan McLeod.

“They leave it to the provinces.”

McLeod thinks it’d be a stretch for the feds to withhold funding from provinces it deems in violation of a particular definition of medical necessity.

But there is an economic argument to be made in making access to health services like abortion more equitable, he said: We know uneven access means people with fewer resources lose out. And we know that people born into families that can’t adequately care for them have poorer health and labour market trajectories — “there’s this inter-generational persistence of disadvantage.”

“If we do prevent access, we’re going to systematically select out the people who probably need it the most.

“Is that the result we want? I think a lot of us would say no.”

‘We know that abortion services remain patchy’

Liberal Health Minister Jane Philpott wouldn’t say whether she’d threaten to withhold health transfers to provinces such as New Brunswick or PEI if they don’t expand abortion access.

But an emailed statement from her office attributed to Philpott said she wants to improve it.

“Our government firmly supports a woman’s right to choose, and believes that safe and legal abortions should be available to any woman who needs it,” Philpott’s statement reads.

“We know that abortion services remain patchy in parts of the country, and that rural women in particular face barriers to access. Our government will examine ways to better equalize access for all Canadian women.”

Which ways, specifically, will the feds examine? No word yet.

“I would like to see governments recognize women’s equality rights and their role in securing them,” Johnstone said.

She’s more confident in the potency of public pressure in the wake of social activism in New Brunswick earlier and PEI this year.

“Those kinds of activities have given me a much more positive outlook than I might have had last year,” she said.

“Unfortunately … it often takes something quite terrible happening for people to recognize a problem and to organize around it.”

But for many women in Canada, Macfarlane says, that’s already happening.

“Every year there’s one or two women or girls rushed to hospital [in PEI] because they’ve attempted a home abortion,” he said.

“This is Canada in the 21st century and this is actually happening … because a province isn’t providing access to a basic health service.

“So that’s a problem.”

Send us your stories: Have you had a rough (or exemplary) experience getting an abortion in Canada? Are you an abortion provider who’s felt targeted (or welcomed) in your community? We want to talk to you.

Note: We may contact you with follow-up questions but won’t publish anything you send us in response to this article without your permission.

Comments