So you’ve bought a steak at your local grocery store for dinner. Want to know about the animal it came from?

That’s not so easy.

If you bought that steak directly from a farmer or a smaller butcher, you may be able to figure it out without too much trouble. But, unlike some other countries, Canada does not have full traceability of meat from farm to fork. As such, much of our meat is comparatively difficult for consumers to track.

READ MORE: Do you want to know what’s in your food? Canadians want more transparency

How the system works

For cattle, every individual animal is fitted with a radio-frequency identification (RFID) tag before it leaves the farm where it was born. That tag, attached to the ear, assigns each animal a unique identification number that is entered into a database. The database includes information on things like its sex, breed, birthdate and location.

As the cow moves from farm to feedlot, its information is updated in the database, and its tag can always be scanned to bring up the data.

When the animal is slaughtered, its tag number is “retired” and its slaughter is recorded.

Here’s where things get difficult. After the animal’s death, it moves into a whole different tracking system.

A single animal is broken down into a number of different parts, which might be sent all over Canada or internationally, according to Ron Davidson of the Canadian Meat Council. The abattoir is required to keep detailed records of which animals go in, and where the meat coming out is sent.

“Federally-inspected abattoirs are required to operate on the basis of distinct production lots,” he said. “Companies must maintain very precise records for which animals are included in each production lot, the processing records for each lot, and to whom the many different products from each lot are marketed.”

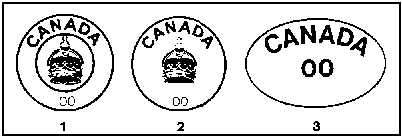

If the meat is fully-packaged at a federal meat establishment and sent to stores in a ready-to-sell condition, the package will display a “meat inspection legend” logo marked with the registry number of the establishment where it was processed, that you can enter into a website to find out about the facility. Meat that is packaged at the store or elsewhere won’t have this logo and as such, you wouldn’t know where it was processed unless you ask.

According to Sylvain Charlebois, professor at the Food Institute at the University of Guelph, most retailers could probably tell you about your meat as far back as the slaughterhouse, if you asked. “They would know when the animal was slaughtered, in what condition, and where it was slaughtered and where it was processed for the second time. They’ll give you information about food-level processing as well and the ingredients added to the meat itself. They’ll be able to give you all that information, but as you get closer to the farm gate, it becomes a little more difficult for them to give you information.”

Get daily National news

Loblaw, the national grocery chain, told Global News in an emailed statement that they believe, “It is important that we have an increased level of transparency about where Canadians’ food comes from.” They have a program, called DNA TraceBack, which allows them to track beef from regional farms to the store, they said. According to the DNA TraceBack website, DNA samples are taken from cattle at the slaughterhouse. As the beef is processed, more DNA samples are taken and matched with those from the original animal so that they can identify which piece of meat came from which cow. The meat is then shipped to stores.

“What this means, is that we can assure Canadians we know where our beef comes from,” wrote Sal Baio, senior vice president, Fresh, at Loblaw. According to Loblaw, the traceability system is used in all Loblaw-owned stores, except No Frills and Maxi. However, none of this system is visible to consumers or meant to be a consumer tool: it just allows Loblaw to be confident in their suppliers and where their meat came from.

How other countries track their meat

In other parts of the world though, consumers in general know a lot more about their meat. In several European countries, said Charlebois, “it’s quite common to go into a store and have access to the address and location of the grower, essentially. You know where the meat came from, what region, and whatnot.” You still have to ask your grocer, but he or she will probably be able to give you more information than the typical Canadian retailer.

Charlebois, who is currently on sabbatical in Austria, said that finding out where his meat comes from is very easy there, due in part to the much shorter supply chain in smaller European nations (it’s a bit more difficult in France and Germany, he said). In North America, because agriculture is often located so far away from urban centres, it’s harder to build full traceability systems, he said.

Europeans are also more aware than Canadians of how agriculture works, he said. “It affects expectations at retail. Consumers, urbanites, not knowing the origin of meat it may not matter as much. But in Europe it does. It seems to matter more. So people ask questions.”

Japanese consumers have an additional tool to track their beef. Packages of domestic beef sold in Japan are marked with a 10-digit identification number. Consumers can enter that number into a government website and find out about the cow they’re eating: its breed, sex, date of birth, its mother’s ID number, where it was raised and where and when it was slaughtered. Even steak and sukiyaki restaurants are required to display this code on the beef dishes they serve.

Could Canada’s beef be tracked?

If Canada adopted a European-style beef traceability system, there would be improvements in food safety, said Charlebois, “but that’s not going to drive companies to invest in food traceability.”

“The bottom line is consumer choice,” said Davidson. “For the vast majority of consumers in Canada, food prices matter. The primary distribution system responds to the choice of these consumers.”

READ MORE: Canadians care more about food price than taste, poll shows

For consumers for whom price is not a constraint, he said, there are parallel traceability systems already in place.

As prices go up across the board though, consumers in general might start demanding changes, thinks Charlebois. “If consumers are paying more for their food, they will expect more. Same goes for knowing the origin of their food, where it came from, how it was raised, what kind of product and what kind of feed was the animal given during its lifetime,” he said.

“As consumers are asked to pay more or invest in their nutrition, the livestock industry will have to accept the fact that consumers will expect more. More data at the point of purchase.”

Consumers will also want assurance that they’re getting what’s written on the label, or that there aren’t undeclared allergens or ingredients in their food, said Charlebois.

But implementing a highly functional traceability system in Canada would be tough, he said. “To actually have a very highly functional traceability system costs a lot of money. And that raises the issue of who’s going to be paying for it. What data are you going to share? If there is a recall, there’s a problem, who’s going to pay for that? Who’s going to be accountable?”

All the same, he thinks Canada should do it. “It’s arguably the most effective managerial system you can have to mitigate risk from farm to fork.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.