OTTAWA – Some 3,500 Liberal volunteers knocked on more than 200,000 doors in 190 ridings across the country last weekend.

Good old-fashioned, boots-on-the-ground campaigning to identify potential supporters for this fall’s election, right?

Not quite.

Those volunteers are the vanguard of the modern style of campaigning that melds traditional person-to-person contact with sophisticated, big data analytics to allow political parties to identify, target and mobilize likely supporters in ways not imagined just a decade ago.

‘Plane Talk’ with Scott Brison: On being gay in Canadian politics and maybe becoming a country singer

The Conservatives were the first to recognize the value of harnessing technology in 2004, adopting techniques pioneered in the United States to create a massive data base of voters known as the Constituent Information Management System. CIMS has given the ruling party a significant advantage ever since, both in fundraising and micro-targeting niches of potential voters.

In recent years, New Democrats and Liberals have been racing to catch up, hiring data analytics experts and overhauling what had been haphazard efforts to amass data bases.

The Liberal party agreed to give The Canadian Press a rare glimpse of how it gathers information on voters and what analysis of all that data enables it to do.

Start with last weekend’s canvassing.

- Trudeau tight-lipped on potential U.S. TikTok ban as key bill passes

- Canadian man dies during Texas Ironman event. Her widower wants answers as to why

- Hundreds mourn 16-year-old Halifax homicide victim: ‘The youth are feeling it’

- On the ‘frontline’: Toronto-area residents hiring security firms to fight auto theft

READ MORE: MacKay departure underscores fact Conservatives are one-man show

Gone are the days of volunteers standing on doorsteps with a clipboards and voters’ lists, ticking off likely supporters. The modern Liberal canvasser now carries a smart phone or tablet, loaded with the mini-VAN app. It was developed by U.S.-based NPG VAN and used to great effect by Barack Obama’s presidential campaigns.

Each volunteer is trained to give a brief homily on why they support the party — the personal touch never gets old — and to then follow a script designed to elicit pertinent information, including party preference, willingness to take a lawn sign, issues of concern, email address and phone number.

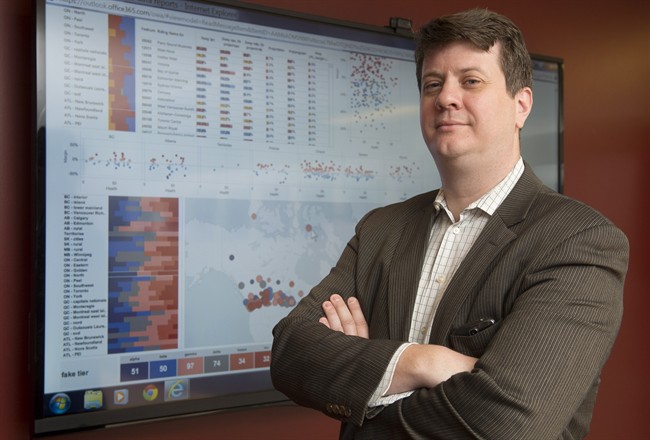

Responses, along with other information such as a voter’s preferred language, are punched into mini-VAN, which is linked to the party’s central data base, Liberalist, where party headquarters can monitor the canvassers in real time. (Fake data was inputted for the demonstration given to The Canadian Press in order to respect privacy).

The party has put as much effort into amassing its volunteer army as it has into analysing the information they collect. Face-to-face contact on the doorstep is still considered the most persuasive means of wooing voters, notwithstanding the avalanche of live and automated phone calls, emails and other instant messaging opportunities.

READ MORE: Does a mandatory CPP increase double an employee’s return or risk job losses?

“Data analytics right now is sort of a bit of the flavour of the month,” says Liberal national director Jeremy Broadhurst.

“But it’s meaningless unless it’s combined with some very long-established, old-fashioned ways of doing politics, which is really about having an army of volunteers.”

He likens it to riding a horse while using a satellite phone to get directions.

“The satellite phone won’t get you very far if you don’t know how to ride that horse.”

Information gathered by canvassers is combined with publicly available demographic data from the national census, polling results and other data mined from responses to party petitions, email blasts and online and social media campaigns to produce what Liberals refer to as analytics dashboards — complex digital graphs and charts.

Dashboards range from a country-wide overview of Liberal prospects down to a microscopic look at voters in each postal code.

Digital sliders on each dashboard allow organizers to input a host of demographic variables — age, religion, language, income, children, educational attainment, employment status and so on.

READ MORE: As Peter MacKay exits stage right, Liberals eye his Nova Scotia riding

Want to see ridings with a 20 per cent Chinese population? There’s a slider for that. Want to find neighbourhoods heavily populated by families with young children and likely to be most receptive to Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau’s proposed enhanced child benefit? There’s a slider for that too.

Want to identify potential swing ridings? Take a chart that ranks the party’s most winnable ridings then use the slider to find out what would happen if the Conservatives gained two percentage points or the NDP dropped two points.

The benefits, in terms of targeting niche audiences or deciding where to expend finite organizational and financial resources, seem obvious.

But while much has been made of the ability of data analytics to slice and dice the electorate into winnable chunks, Broadhurst maintains the importance of micro-targeting is overblown.

A bigger benefit, he says, is the ability of the party to monitor the health of its ground campaign and diagnose problems. Liberal headquarters has used data analytics to assign a health score to each riding, based on factors like the size of its war chest, the number of doors knocked on and number of follow-up phone calls placed.

This can be cross-referenced with winnability rankings to fix problems in ridings that are not living up to their potential. Or it might reveal ridings initially thought to be losers but where the local campaign is thriving and where a timely visit by the leader or an influx of organizers could result in an upset.

“It’s about . . . being able to make smart, strategic decisions that are based on something that is more than just the traditional ways, which was really kind of a combination of high-level polling and kind of gut instinct,” says Broadhurst.

“This is really more evidence-based decision making.”

Comments