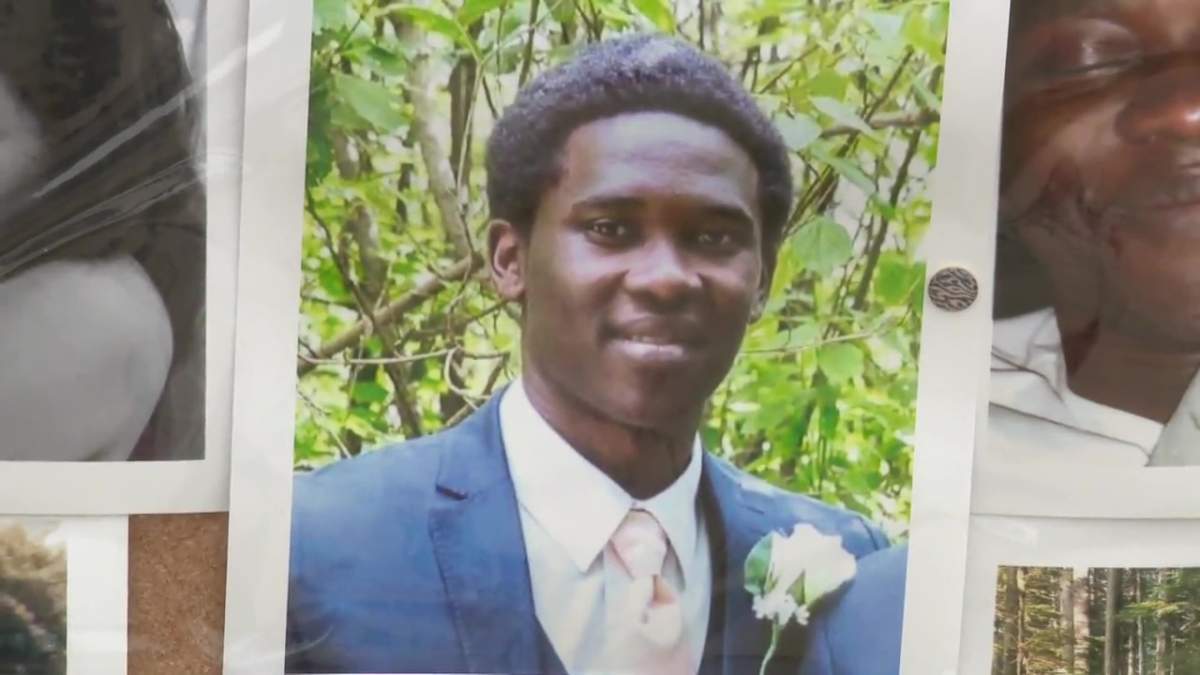

New security camera video shows what happened in the fatal encounter between Mathios (Matthew) Arkangelo and an Edmonton police officer.

It depicts the young man standing in front of an Edmonton police officer, with his arms raised, holding something in one of his hands. He took a step forward and the officer fired his gun.

The video obtained by Global News shows the Saturday, June 29 shooting in the Fraser area of northwest Edmonton. It comes as Alberta’s police watchdog is investigating the shooting.

The Alberta Serious Incident Response Team said the situation began with a single-vehicle rollover on Anthony Henday Drive near 153rd Avenue just before 9 p.m.

A 911 caller said the man driving the vehicle had left the scene on foot, so police began canvassing the surrounding neighbourhoods of the community of Fraser.

At approximately 9:11 p.m., the EPS Air 1 helicopter team was asked to help and began flying over the area.

A description of the driver was provided to EPS officers and at 9:21 p.m., one radioed in that they’d spotted a person matching the description.

ASIRT said the man walked in the direction of the police SUV as the officer drove the vehicle, with emergency lights activated, toward him. At approximately 9:22 p.m., the subject officer stopped his vehicle and stepped out, facing the man.

The one-minute and 38-second video begins at 9:23 p.m. The camera was mounted on a nearby home. The video is silent.

The Edmonton Police Service SUV is seen in the middle of the street, lights still activated.

ASIRT said the man raised his arms to his sides while facing the officer, who had his gun drawn, and the two engaged verbally with each other. The subject officer fired his gun at the man, who was hit and dropped to the ground.

The video, along with footage from other angles, confirms that series of events.

Arkangelo is seen standing in front of the cruiser with his arms raised at his sides when he is hit. One of his arms falls and an object in his hands appears to drop to the pavement. It’s not clear what it was.

The 28-year-old takes two steps backward, moves forward five steps and then stops. It’s not clear if more shots were fired. Arkangelo then stops, lies down on the road and rolls onto his back. For the next minute and 20 seconds, he lay on the road, occasionally moving his arms and legs.

“I’ve got a lot of questions about what happened here,” said Edmonton criminal defence lawyer Tom Engel, whose practice regularly involves law enforcement issues and is an outspoken critic of poor conduct. He is representing Arkangelo’s family, whom he said are grief-stricken and outraged.

Get breaking National news

“It seems like he was just gunned down.”

At no point between when the bullet was fired and the video ends — a minute and 36 seconds later — does anyone approach Arkangelo.

Another video from about three minutes after the shooting shows several officers standing around Arkangelo’s body on the ground.

ASIRT said he was provided medical attention at some point but died as a result of gunshot wounds.

“Quite often in shootings by police that are fatal, they will say in their media release that the officers immediately rendered first aid trying to save the life of the person they just shot. Here, that did not happen,” Engel said.

“That did not happen and that’s very disturbing too.”

Whether that would have made a difference in saving Arkangelo’s life is unclear. Engel said the medical examiner’s report will provide more answers eventually.

Engel said officers are trained to only shoot when they believe their life is at risk.

“They have to have the belief that they are under threat of grievous bodily harm, or somebody else is under the threat of grievous bodily harm before they can shoot. I don’t see anything like that,” he said, adding he believes kids were playing in the neighbourhood at the time.

“Where are those bullets going to go? It’s (a) reckless disregard for the safety of others as well.”

Both Arkangelo’s family and Engel believe the man had a knife on him, which they said he used for work. It’s unclear in the video what was in his hand when it was dropped. ASIRT’s update on Tuesday did not make reference to any weapons recovered at the scene.

Criminologist Dan Jones used to be an Edmonton Police Service officer and found himself in situations where he could have fired his service weapon, including an incident on Jasper Avenue where a person was approaching him with a knife.

He said many things go through an officer’s mind in those moments. He added officers are trained not to approach an injured person or suspect when they are alone or without backup.

There has been an increase in officer-involved incidents in recent years. ASIRT released statistics for the first half of 2024 last week, saying it had 42 new files — putting the agency on pace for its busiest year ever.

Jones can’t definitely say why there has been an increase in police shootings, but believes it stems from a societal shift that happened in the wake of the 2020 murder of George Floyd — an African American man who was murdered by a white police officer in Minneapolis, Minn.

“My speculation — there is some research to back this thought up, though — is, as police legitimacy has reduced as a result of the murder of George Floyd and so many other issues, it becomes more acceptable to attack the police because the police aren’t seen as a legitimate power holder.”

“That’s where the use of force increases. Police have to use force more because they’re not seen as legitimate and people don’t want to listen to them. People don’t want to take it. And I think that’s what’s happened over the last several years — there’s been a decline in police legitimacy.”

Both Engel and Jones say decisions not to prosecute recent high-profile cases in Edmonton may have changed public attitudes.

Pacey Dumas was left with life-altering injuries after an officer kicked a young man in the head in December 2020. He was not armed and had no criminal history.

Half a year later, Steven Nguyen, 33, was fatally shot by police in June 2021 while walking in a neighbourhood near his home and holding a cellphone that police said was mistaken for a gun.

In both cases, ASIRT said there were reasonable grounds to believe an offence was committed, but the Alberta Crown Prosecutor Service declined to lay charges.

“The Pacey Dumas case and the Stephen Nguyen case where ASIRT recommended charges and no charges were laid — that’s not the police’s fault, but that reduces police legitimacy,” Jones said.

Dumas is Indigenous and Nguyen was Asian. Arkangelo was Black. Engel said such incidents further erode trust in police amongst communities of immigrants who have moved here from regions where law enforcement was already not viewed favourably.

“In that community, which is predominantly Nigerian heritage and East Indian, culturally there is a lot of distrust in that community,” Engel said, adding an idea being explored is having a trusted community liaison involved in helping witnesses open up to ASIRT investigators.

ASIRT investigations often take months, if not years, to conclude. In the meantime, Jones said friends and family are left without any explanations as they grieve the death of their loved one.

“Even if that explanation is legitimate and justified, it’s not going to matter two years from now. People want to hear about it now, but they can’t because the investigative integrity,” Jones said.

The Edmonton Police Service has said it cannot provide additional information due to the ASIRT probe.

Comments