A couple of decades ago, I mentioned during a radio show that I’d acquired several bootleg records by several bands I absolutely adored, mostly live recordings, some outtakes and alternative mixes. A few days later, I received a letter from the head of a music industry organization in which I was called “morally reprehensible” for trading in illegal recordings. He also had a few other choice words for me.

I didn’t care. I’d bought all the albums, all the singles, all the T-shirts, had been to all the shows, and I still wanted more from my favourite acts. But in those days, the supply of music was strictly controlled by record labels. The only option that existed between gaps in the album/touring cycles was to go the bootleg route. Yes, these were illegal releases that lived outside contracts and agreements. And yes, in most cases, the proceeds from the sales of these records didn’t make their way back to the artist. But once infected with the bootleg bug, it was tough to quit. And hey, I was just following a tradition that went back a hundred years.

The bootleg industry goes back to Lionel Mapleson, the official librarian at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. In 1900, he bought Bettini, a phonograph based on Thomas Edison’s talking machine. He was immediately smitten with its recording capabilities. On March 22, 1900, he wrote, “For the present, I neither work properly nor eat nor sleep. I’m a phonograph maniac!! Always making or buying records. The Bettini apparatus is simply perfect.”

Mapleson immediately began to record performances at The Met from a perch high on a catwalk 40 feet above the stage. Although he stopped after a couple of years — someone at The Met got wind of what he was doing — about a hundred of these recordings have survived and are now considered to be priceless documents of that era. They now live at the Library of Congress.

Fast-forward to the ’40s and ’50s. Hardcore jazz fans were frustrated at the inability of record labels to keep up with the demand for new records. Taking matters into their own hands, they used bulky reel-to-reel machines set up in the audience to record performances by Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and other legends. Much of that era of jazz would have been lost to history had it not been for the obsessives determined to capture these gigs.

When it came to rock, everything began to change in July 1969 when two enterprising hippies known as “Ken” and “Dub” somehow came into possession of 24 unreleased Bob Dylan recordings made between 1961 and 1967, consisting of everything from TV show appearances to studio outtakes to demos recorded in a Minnesota hotel room. Dylan was one of the biggest artists in the world at the time and Ken and Dub believed that everyone needed to hear these important recordings. They found someone to press up a double vinyl record for their own label, which they called Trademark of Quality. It eventually became known as Great White Wonder.

The floodgates opened with Great White Wonder. Demand for bootleg records featuring The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin and dozens of other acts skyrocketed. In some cases, record labels were forced to counter a live bootleg with an official live album. We wouldn’t have the Stones’ Get Your Ya-Ya’s Out if not for a bootleg entitled Live’r Than You’ll Ever Be.

Where did these recordings come from? Fans found sneaky ways of getting recording equipment into shows. Sometimes there was a leak from whoever was doing the sound at a show or engineering a recording session. There were break and enters where tapes were stolen. Dumpster diving in the garbage of recording studios resulted in the discovery of recordings that were just thrown out. It’s alleged that a cassette of demos was liberated by a mechanic who “found” it while Bruce Springsteen’s car was being serviced.

Once acquired, bootleggers sourced out record plants that didn’t have solid relationships with labels. They’d happily take on jobs pressing up albums that were of dubious provenance.

There were some prosecutions, but that also meant running afoul of the mob, which also had its hand in the business. Some bootleggers were out of reach. For example, in the 1980s, there were accusations that proceeds from the sale of bootlegs were being funnelled into the coffers of the Irish Republican Army. There was also the trade at the “triple frontier” where the borders of Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay met. It’s also possible that organizations like the Russian mob and al-Qaeda once had a piece of the action.

Complicating matters was the patchwork of copyright laws around the world. In some countries, bootlegs were perfectly legal. In others, there were loopholes in the law that allowed them to exist. In Greece, for example, police were banned from university campuses under the country’s pro-democracy laws. Guess what you could buy? And in countries like Russia, China, Vietnam and Indonesia, there was no will to crack down on illegal recordings that were openly sold in stores and markets.

Things became even more interesting with the arrival of the compact disc. One of the better-known companies during this time was KTS, short for Kiss the Stone. Operating at first in Europe (probably in the principality of San Marino), the company made dozens of extremely high-quality bootlegs available. But then American federal agents set up a sting operation that lured a bunch of bootleggers to Disney World. Thirteen people were promptly arrested, including someone from KTS. It briefly resurfaced (I think) in Singapore but as far as I know, KTS is completely gone.

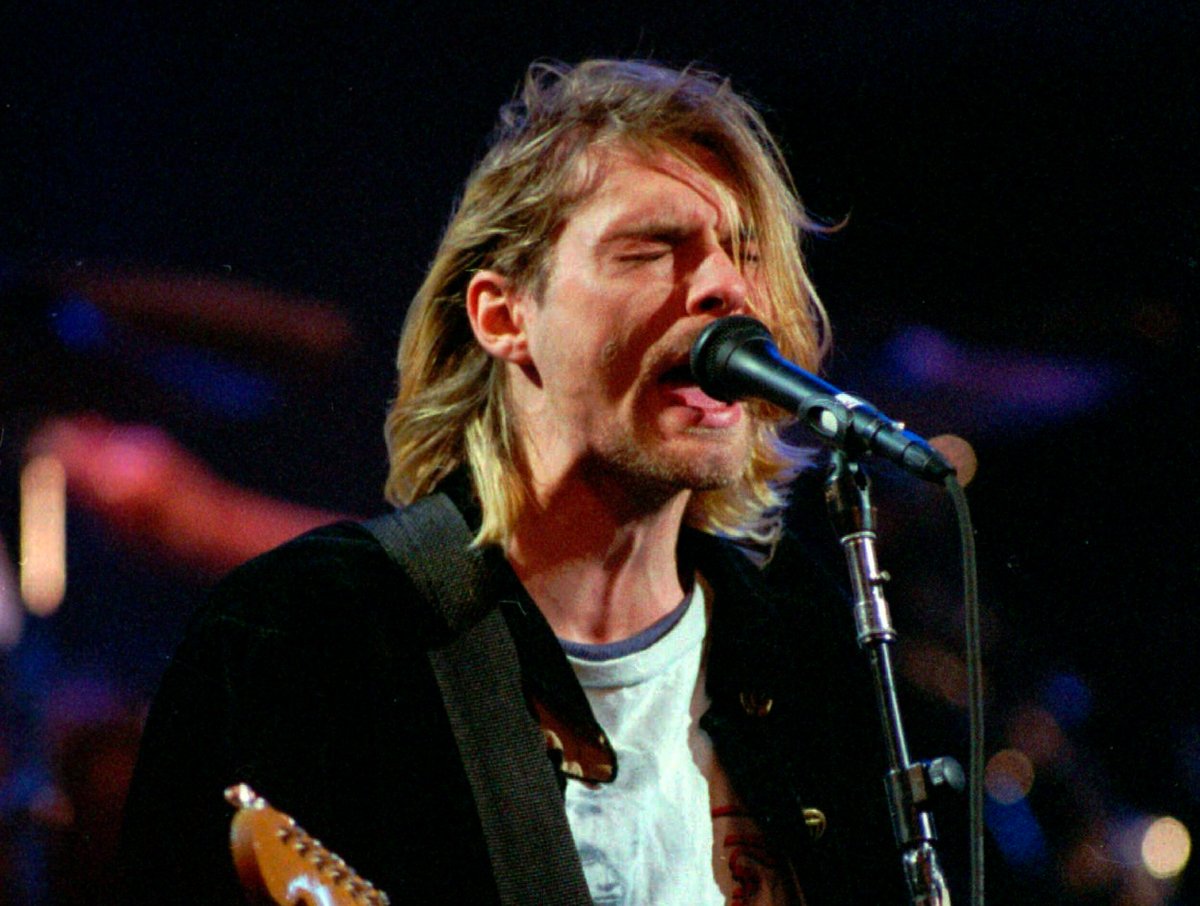

Industry people cheered this, but had it not been for labels like this, there would be no record of important events. One KTS CD in my collection documents Nirvana’s last-ever concert before the death of Kurt Cobain. That’s history.

In fact, most old-school bootleggers seem to have gone extinct. The rise of online file trading made it unnecessary to hunt for these hard copy recordings while enforcement is more co-ordinated and international than ever before. Outside of some vinyl I’ve seen in U.K. record shops (a loophole allows for bootleg-like live recordings to be sold), the market has all but dried up. The big problems today are stream ripping, fake streams and stream manipulation.

I used to visit a particular store in the French Caribbean on the second-last day of our vacation. I have no idea who supplied this shop but his suppliers of bootlegs were incredible, especially when it came to acts like Oasis and Nine Inch Nails, two of my favourites. One year when I dropped in, I saw that his stock had diminished greatly.

“Where are all those great rare records of live shows and demos you used to sell?” I asked.

“Monsieur,” he replied sadly, “they are all gone. I cannot get them anymore.”

A year later when I went back to visit, the store was gone. I haven’t bought any morally reprehensible records or CDs since.

Comments