It happened again at the gym. In the middle of my workout, some godawful song started playing: another wretchedly over-Auto Tuned melody-less mid-tempo mumble rap thing with zero energy. It just meandered aimlessly for about four minutes before segueing into something else. My reaction was both emotional and physical. How could anyone possibly think this was good music? And this is what the kids are listening to these days? What’s wrong with them?

That’s when it hit me one more time: I must be old.

Such a come-to-Jesus moment is concerning for me. I listen, analyze, and evaluate music professionally. It’s literally my job. I spend on average eight hours a day listening to all manner of music with a critical ear as part my process for creating programs like The Ongoing History of New Music and posts for Global News, Corus Radio, and my own website, ajournalofmusicalthings.com. I’m constantly being invited to speak on music for both public and private events. I moderate and appear on panels at conferences around the world. Radio stations and news channels as far away as Israel have me on speed dial when they need someone to comment on something happening in the world of music. I need to be up-to-date on everything that’s happening in the world of music.

But even though I can maintain a neutral analytical position — well, most of the time — I will confess that a lot of contemporary music leaves me cold. It’s just … bad.

Listen, I realize that every generation has a right to believe that the music of their youth is the greatest music of all time. This is all part of the cycle of life, a cycle of oldsters hating the music of the young. Here’s an example of an old dude railing against what the damn kids are listening to:

“Forms and rhythms in music are never altered without producing changes in the entire fabric of society. It is here that we must be so careful, since these new forms creep in imperceptibly in the form of a seemingly harmless diversion. But little by little, this mischief becomes more and more familiar and spreads into our manners and pursuits. Then, with gathering force, it invades men’s dealings with one another and goes on to attack the laws and the constitution with reckless impudence until it ends by overthrowing the whole structure of public and private life!”

Familiar sentiments, yes? Those words were written by Plato about 2,400 years ago. Attribute this one to St. Basil, a fifth-century cleric”

“There are towns where one can enjoy all sorts of histrionic spectacles from morning to night. And, we must admit, the more people hear lascivious and pernicious songs, which raise in their souls impure and voluptuous desires, the more they want to hear.”

And finally, there’s this quote from John S. Dwight, a composer of hymns who lived in the 19th century.

My point is that when it comes to elders looking down on the music of youth, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Get breaking National news

As we age, life begins to interfere with our engagement with music. Jobs, families, mortgages — all the responsibilities associated with being an adult get in the way. We no longer have the time or energy to devote to music, either listening or going to shows. And because we’ve settled into who we are as people, we no longer need to use music to discover who we are nor do we need to use it to project our identities to the world.

There have been a number of studies on how and why our tastes in music change as we age. The latest comes from Spotify in the U.S. and users of Amazon Echo users. It found that by the time they turn 33, people start finding new music as a “racket.” Oldsters (>33) start to uncover music from their teens that was less popular back as they find modern music less relatable than what they were listening to during their crucial coming-of-age musical years (approximately 13 to 23). We go back and mine the past for something new, songs we apparently missed the first time around.

Men tend to start disparaging current music first, starting in their early 20s with women following soon after. Looking at a related study, it was found that men are more critical with 51 per cent declaring that the music from when they were young was better than anything being made today. Women are a little more forgiving but 41 per cent still agree with their male counterparts. In other words, men tend to be more nostalgic sooner than women when it comes to music.

By the time we all reach our 30s — like I said, the magic age for this seems to be 33 — our tastes in music have matured and, in some cases, solidified. The music of our youth becomes comfort food, the songs we return to again and again. If you have kids who are into music, you tend to run from their tunes — i.e. contemporary sounds — faster. You reach the fed-up stage an average of four years earlier. This means that if you had kids early, you may have grown sick of today’s music by the time you’re 27.

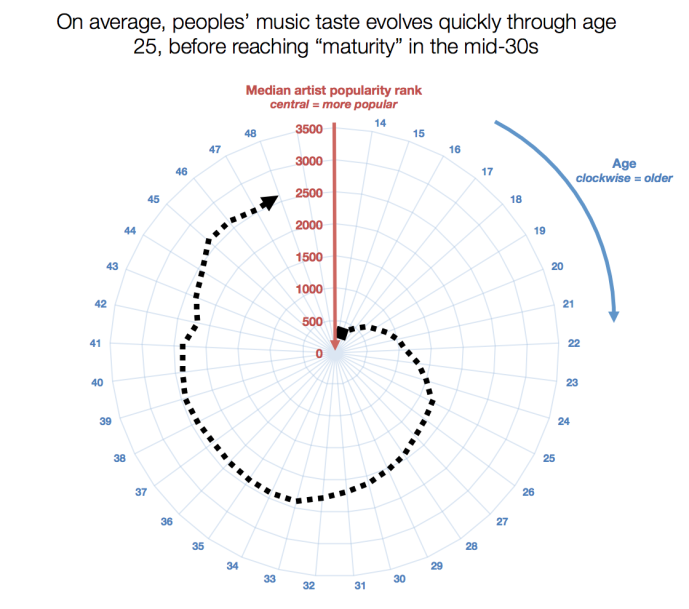

Another study says there’s a slight alteration around age 42. That’s when many of us rebel against middle age by thinking, “I’m not old! I’m still down with music! I’m going to get back into the scene.” You can see the slight wobble in this graphic of the Coolness Spiral of Death where the trend toward nostalgia experiences a slight reversal before righting itself.

That burst of energy lasts anywhere from 12 to 18 months before we give up and give in to our nostalgia. From there it’s all Grandpa Simpson.

I’m generalizing here, of course. There are people who remain lifelong addicts to new music and are willing to bob and weave with trends, cycles, and fads. Other once-heavy consumers of music start to notice older sounds repeating themselves. Beauty School Dropout is pretty cool, but aren’t they just the descendants of Blink-182? And didn’t Green Day begat Blink? And what’s Green Day but another version of what The Ramones were doing in 1977? Has culture stagnated?

It’s part of the cycle of life that goes back thousands of years. Embrace it, deal with it, and listen to what gives you joy. But if you’re feeling like complaining, take a look at this analysis.

Comments