Russia is using Interpol to find and arrest dissidents abroad, including those who criticize the war in Ukraine, exiled political opponents say.

“I am in a constant state of fear and uncertainty,” Artur Zaripov told Global News from his home in Poland, where he says he’s been detained since Russia requested that the international police organization issue warrants for his arrest, which are called Red Notices.

Zaripov is a Turkic Muslim from the Russian Republic of Bashkortostan and a vocal campaigner for Bashkortostan independence.

In 2017, his political activism landed him in a Russian prison, accused of terrorism. After 18 months, he was released on house arrest and escaped the country.

He’s now living in Warsaw, where he says Polish police have detained him at Interpol’s behest four times over the past 18 months.

In each instance, he’s been released once authorities realized the charges were baseless. But he fears he could be extradited back to Russia.

“European countries know Putin is a liar,” Zaripov said. “I don’t understand why they are still cooperating with Russia through Interpol.”

Interpol, which turns 100 years old in September, does not employ its own police officers but rather is used to share information about alleged criminals. The world’s largest international police organization, Interpol includes 195 member states, but Russia is single-handedly responsible for 38 per cent of all public Interpol “Red Notices,” which are the requests it sends to “law enforcement worldwide to locate and provisionally arrest a person pending extradition, surrender, or similar legal action.”

Get daily National news

Interpol’s constitution forbids notices that are politically motivated, and the organization says all Red Notices are subject to compliance reviews. Its critics say those reviews are insufficient.

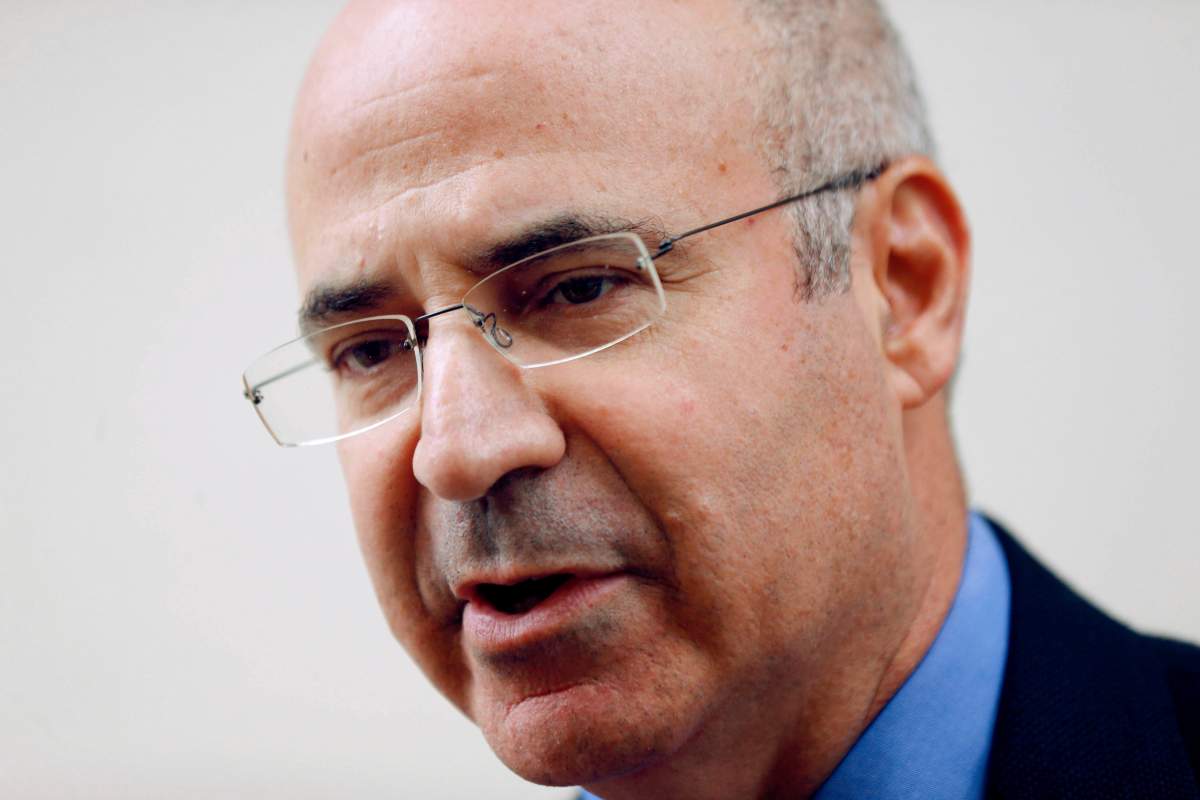

“Russia is killing hundreds of thousands of people and soldiers in Ukraine and bombing the whole country, creating millions of refugees. The fact that they can use Interpol to go after their enemies is shocking,” said Bill Browder, a prominent Kremlin critic and anti-corruption campaigner.

Following the invasion of Ukraine last year, Canada, the United States and other Western governments called for Interpol to suspend Russia.

In a statement, Interpol said its founding charter stipulates it must remain politically neutral and “maintain police cooperation and ensure communication channels remain open … nor is there any provision in the Constitution for the suspension or exclusion of a member country.”

However, Interpol’s critics note the organization is, in fact, able to restrict member states’ access to its information exchange network, a measure Interpol took against the Syrian regime between 2012 and 2021.

Browder said Russia has tried to issue Interpol notices against him on eight occasions. He was arrested in Spain in 2018, sparking a global outcry.

“And it was only because I tweeted out when I was being arrested that a whole international firestorm was created. But for a lot of people, that wouldn’t happen. And they end up sometimes incarcerated for a hell of a lot longer than a day or two.”

Other recent examples include Ukrainian opera director Yevhen Lavrenchuk, who was detained in Italy for two months last year on a Red Notice.

Another case involved Chechen Amina Gerikhanova, who was arrested in Romania last year and separated from her eight-year-old son. She spent eight months in detention and was ordered extradited back to Russia until the European Court of Human Rights intervened. She has since been granted refugee status, which nullified the Russian request.

“Usually the accusation that’s made against them is that they’re members of a terrorist organization or that they support terrorism, and that flags them for security and immigration officials in Europe and makes them vulnerable to deportation,” said Yana Gorokhovskaia, a research director at Freedom House, a U.S.-based non-profit that tracks cases of transnational repression.

“The volume is so large, we’re talking tens of thousands of notices, that Interpol can’t really check them all. And so of course, things slip through,” she said.

In September 2022, after being detained in Poland for the third time, Artur Zaripov appealed his Interpol notice to the Commission for the Control of Interpol’s Files (CCF), an independent body that’s meant to ensure all personal data processed through Interpol’s channels conforms to the rules of the organization.

Now 10 months later, he is still waiting for the CCF to issue a ruling on whether his Interpol notice should be revoked.

“Russia right now creates mayhem all over the world,” Zaripov said. “If I am extradited to Russia, what will happen to me?”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.