The long-anticipated Mass Casualty Commission’s final report into the 2020 Nova Scotia shooting highlighted significant systemic issues within Canada’s national police force and called for widespread changes.

“The future of the RCMP and of provincial policing requires focused re-evaluation,” said the report titled Turning the Tide Together. “We need to rethink the role of the police in a wider ecosystem of public safety.”

The wide-ranging report examining the tragedy was publicly released in a series of volumes Thursday, totalling more than 3,000 pages.

It touched on a variety of issues, including the police response, the killer’s access to firearms, the role of gender-based violence and the steps taken to inform the public as the rampage unfolded.

“The commission’s mandate was broad in scope and ambitious in its timeline,” said commission chair Michael MacDonald Thursday, addressing a crowd gathered at the Best Western Glengarry hotel in Truro, N.S., for the public release of the report.

“It required us to investigate the causes, context and circumstances giving rise to the mass casualty, police responses, and steps taken to inform, support and engage victims, families and affected citizens.”

The report detailed the RCMP’s various failures in preventing, responding to, and reacting in the aftermath of the tragedy, and said the institution as a whole needs to be re-examined.

“There were many warning signs of the perpetrator’s violence and missed opportunities to intervene in the years before the mass casualty. There were also gaps and errors in the critical incident response to the mass casualty as it unfolded,” the report said.

“Additionally, there were failures in the communications with the public during and in the aftermath of the mass casualty.”

Over the course of 13 hours on April 18-19, 2020, a gunman killed 22 people, including a pregnant woman, across three Nova Scotia counties. He was at times dressed like a Mountie and driving a replica RCMP vehicle.

It was the deadliest mass shooting in modern Canadian history.

The rampage ended when the perpetrator was fatally shot by two RCMP officers at a gas station in Enfield, north of Halifax.

The inquiry into the tragedy – fought for and won by family members of the victims – included 76 days of public hearings, more than 7,000 exhibits and source materials, and 230 witnesses.

“The commission’s work was grounded in the memories of those whose lives were taken and all those affected,” MacDonald said during his remarks.

“We paused to remember them each day during public proceedings and carried their names with us while we worked.”

MacDonald said the mass casualty was “not an isolated incident, but the product of a complex web of context, causes and circumstances.”

RCMP under scrutiny

The commission’s final report included 130 recommendations, 75 of which were about policing.

“Significant changes are needed to address various community safety and well-being needs of the 21st century,” commissioner Leanne Fitch said Thursday.

“To do so, the existing culture of policing must change.”

One of the recommendations called for the federal minister of public safety to commission an in-depth, external and independent review of the RCMP.

It said the review should “specifically examine the RCMP’s approach to contract policing and work with contract partners, and also its approach to community relations.”

Following the review, it said Public Safety Canada and the federal minister of public safety should establish “clear priorities” for the RCMP, and identify what responsibilities can be reassigned to other agencies – “including, potentially to new policing agencies.”

“This may entail a reconfiguration of policing in Canada and a new approach to federal financial support for provincial and municipal policing services,” it said.

The report took note of a “long history of efforts” to reform the RCMP’s contract policing services model, but they have “largely failed to resolve long-standing criticisms.”

Commissioners also recommended “modernizing” police education and research by scrapping the Depot model of RCMP training by 2032, and establishing a three-year degree-based model of police education for all police services in Canada.

Get breaking National news

Communication took ‘far too long’

The report also examined RCMP communications, and lack thereof, as the event unfolded.

Since the tragedy, the Mounties have faced intense public scrutiny for providing updates exclusively through Twitter.

“This failure to consider issuing an emergency broadcast reflects a systemic failure on the part of (the Nova Scotia RCMP), over several years, to recognize the utility of Alert Ready for its emergency public communications,” the report said.

Initially, the Nova Scotia RCMP tweeted at 11:32 p.m. on April 18 that officers were responding to a “firearms complaint” – even though at that time the Mounties were aware an active shooter had already murdered multiple people in Portapique, N.S.

That would be the only information shared publicly by the RCMP until 8 a.m. the next morning.

“To the extent that the 11:32 p.m. tweet underplayed the seriousness of the threat to the public, the RCMP had ample opportunity to correct the public record,” the report said. “It took far too long to do so.”

Police were also slow to share that the gunman was disguised as an RCMP officer on April 19, despite having known that detail for hours.

“The RCMP’s failure to publicly share accurate and timely information, including information about the perpetrator’s replica RCMP cruiser and disguise, deprived community members of the opportunity to evaluate risks to their safety and to take measures to better protect themselves,” it said.

Commissioners recommended that the RCMP amend its policies, procedures and training to include that police activate public communications staff as part of its critical incident response package.

The report said there are “widespread beliefs” that issuing an emergency alert causes people to panic — beliefs that are not supported by evidence.

It urged the RCMP to incorporate material that identifies and counters these beliefs in its training materials.

“These myths have no legitimate place in police decision-making about whether to issue a public warning about an active threat to community safety,” it said.

Commissioners also called for a national review and redesign of the public alert system.

Red flags, warnings and gender-based violence

The report also said there were “red flags” about the shooter’s violent behaviour before the shooting, and there were “missed opportunities” for prevention.

“On several occasions, individuals reported him to the police and other authorities,” it said, adding that only one report resulted in a criminal charge – it was for assaulting a teenage boy.

“The perpetrator also uttered threats to commit violence using firearms against his parents in 2010 and against the police in 2011. Both these threats were reported to the police.”

Neighbours also reported the shooter’s possession of illegal firearms to police.

MacDonald, the commission chair, noted in his remarks that “no person or institution” could have predicted the shooter’s actions, but “his pattern and escalation of violence could have and should have been addressed.”

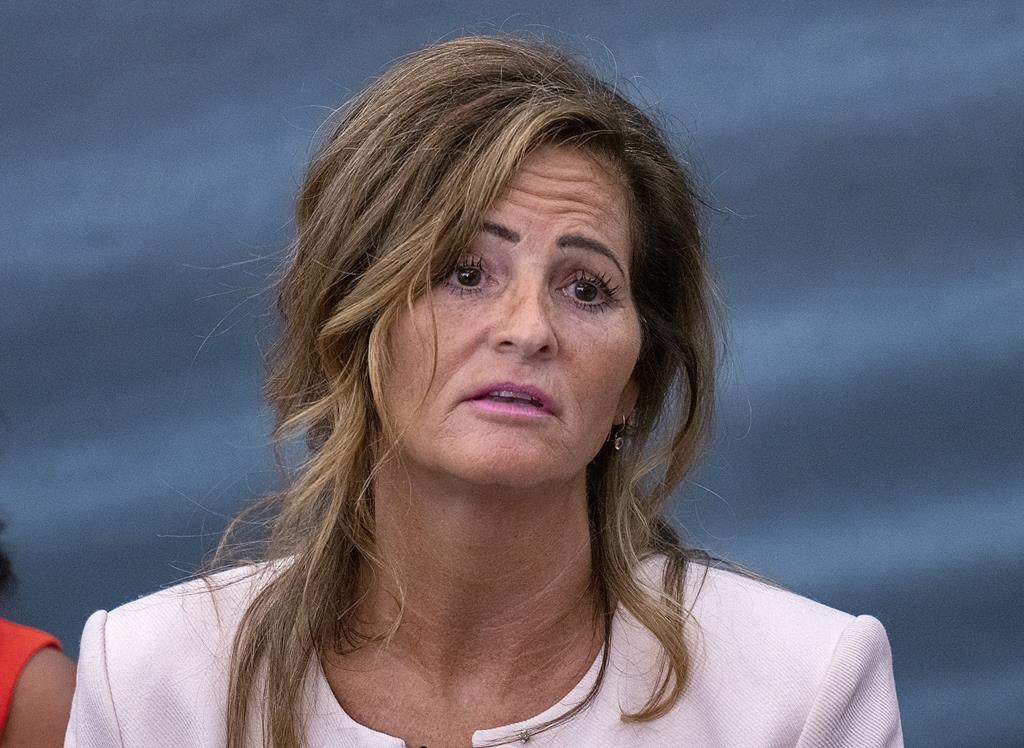

The perpetrator was abusive toward his common-law spouse, Lisa Banfield, and the abuse had been reported to police on at least one occasion in 2013.

Controlling behaviour escalated in the weeks before the shooting, and the mass casualty event began after the gunman assaulted Banfield. She was able to escape and spent the night hiding in the woods.

“The evidence shows clearly that those who perpetrate mass casualties often have an unaddressed history of gender-based, intimate partner or family violence,” MacDonald noted.

“Many mass casualties begin with an act of such violence. That was the case here in Nova Scotia in April 2020, and we saw that again in Saskatchewan in September 2022.”

In the report, commissioners said the RCMP “revictimized” Banfield, in what they said was an “example of some of the ways in which we fail to address gender-based violence.”

“The RCMP did not treat Lisa Banfield as a surviving victim of the mass casualty; that is, as an important witness who required careful debriefing and who would need support services,” the report said.

It said Banfield, who would be charged with supplying ammunition to the killer, was unfairly blamed for the mass shooting, reflecting myths that “a woman is responsible for her partner’s actions.”

This has a “chilling effect” on other survivors of gender-based violence, it said. The report recommended that police learn to better understand the dynamics of intimate partner and gender-based violence.

The charge against Banfield was withdrawn after she participated in a restorative justice process.

Governments should work with community-based advocacy and support groups “to develop and deliver prevention materials and social awareness programs that counter victim blaming and hyper-responsibilization … of women survivors of gender-based violence,” it said.

Commissioners also suggested that firearms licences be revoked for those convicted of domestic violence or hate-related offences.

Implementing recommendations

Commissioners noted that no one person has the authority or responsibility to implement all of their recommendations.

“Implementation … is a responsibility shared among many agencies within the Canadian and Nova Scotian public safety systems and a large group of other actors and agencies, including community groups and members of the public,” the report said.

The commission recommends the federal and provincial governments establish and fund an implementation and mutual accountability body on an “urgent basis.”

“This body will be responsible for creating an implementation plan and providing regular updates to government and to the public,” it said, adding that this body should produce its first public report by the end of the year.

It asked that its framework, funding and founding chair be in place by May 31, with membership being appointed by Sept. 1.

During his remarks, MacDonald said addressing the underlying causes of violence takes “courage, commitment, and collaboration.”

“We recognize this is not the first report to make findings and recommendations like these, but with your help it could be the last,” he said.

“Future acts of violence are preventable, if we have the will to do what is necessary.

“We all have work to do. It is time to act.”

‘It’s going to make changes’

Scott McLeod, whose brother Sean was killed in the shooting, told reporters after the report’s release that having the opportunity for the victims’ families to be heard was a “fantastic thing.”

“It’s going to make changes,” he said.

“Nothing will bring my brother back, or anyone we lost in this horrible ordeal, but we have to … move things forward.”

Nova Scotia Premier Tim Houston, speaking with reporters Thursday afternoon, said there were “lots of recommendations, lots to think about” in the report.

He said the province is “on board” with an oversight committee, and intends to start there.

“There’s a lot of work that’s gone into (the report,) we’ll take it with respect, and we’ll do what we can to make communities safer as quickly as we can,” he said.

Houston also said the province is “anxious to have those discussions” about policing in Nova Scotia.

“Our only objective is to make sure people are safe in our communities,” he said.

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who was in Truro alongside Public Safety Minister Marco Mendicino and Immigration Minister Sean Fraser for the release of the report, vowed that his government will enact changes.

“We will take the time now to properly digest and understand the recommendations and the conclusions and the opportunities that the commission has put forward for us to take up,” Trudeau said.

“There’s no question there need to be changes and there will be, but we will take the time to get those right.”

Asked if the federal government would commit to an independent, external review of the RCMP, as called for in the report, Public Safety Minister Marco Mendicino said they will study the commission’s recommendations “very carefully.”

“We will make whatever changes are necessary to restore the trust between the RCMP and the community here, and to do whatever is necessary to prevent a tragedy like this from happening,” he said.

RCMP responds

During a news conference Thursday afternoon, RCMP commissioner Mike Duheme said he was “deeply sorry for the unimaginable pain” caused by the mass casualty event, and said the RCMP was committed to learning from the tragedy and rebuilding trust.

He stopped short of apologizing for the mistakes made by the RCMP.

“I know our RCMP employees worked to the best of their abilities and did everything they could with the training and equipment they were provided,” he said.

“But we must learn, and we are committed to doing just that.”

Duheme said since the shooting, there have been “significant advancements” in public alerting. He also said the RCMP has put a team in place to study the report, and said police are “committed to learning from the tragedy.”

Dennis Daley, the commanding officer of the Nova Scotia RCMP, said police have implemented a number of changes since the shooting, including enhancing resourcing for its emergency response team, investing in new equipment, opening an operational communications centre, adding additional training and protocols around critical incident command and management and working to improve relationships with policing partners.

“I know our response (in April 2020) wasn’t what you needed it to be, and for that I’m deeply sorry,” he said. “We can’t change what happened in 2020, but we can, and we will, learn.”

— with files from The Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.