Editor’s note: This is a corrected story. A previous version erroneously stated that the saddle and pipe would be stored at the Chief Poundmaker Museum. In fact, the family says they hope to open a separate museum dedicated to the leader where the items will eventually be stored.

Century old artifacts belonging to a 19th century Plains Cree chief who was known as a peacekeeper were returned to his descendants in a repatriation ceremony at the Royal Ontario Museum.

The Toronto-based museum transferred a ceremonial pipe and a saddle that belonged to Chief Poundmaker back to members of his family on Wednesday.

Pauline Poundmaker, or Brown Bear Woman, has been leading efforts to repatriate her great-great-grandfather’s belongings and sacred objects from collections held in Canada and internationally.

“It’s an honor to be the generation that’s able to bring these artifacts home,” she said in a phone interview.

Under Poundmaker Cree Nation laws, descendants are required to initiate and lead repatriation.

Pauline Poundmaker travelled this week from Saskatchewan to Toronto with nine others, including other direct descendants, to partake in a repatriation ceremony with staff at the museum.

- Trustee says they were ‘fully cut off’ from information on Ford government takeover

- Metrolinx sheds 400-plus consultants as agency grapples with growing mandate

- Ford government takes over 8th Ontario school board, sidelining trustees

- Canada’s most wanted fugitive arrested over fatal Yorkdale mall shooting

It was the first time she got to see the two items in person.. The special moment was sacred and emotional, she said.

“I had a moment there where I couldn’t hold back the tears. The significance of being here and the honour it is to be able to bring these artifacts home. It’s hard to describe.”

Get daily National news

Wednesday’s event included First Nations drumming and dancing as well as prayers from local Cree elders. The family spoke of the significance of Poundmaker’s contributions to present-day Canada.

Valerie Huaco, deputy director of collections and research and chief innovation officer, said the museum has been doing repatriation work for 40 years but this event was unique because it was done with an audience at the request of the Poundmaker family.

“We want these events to be guided by the wishes of the nation,” she said in a phone interview following the ceremony.

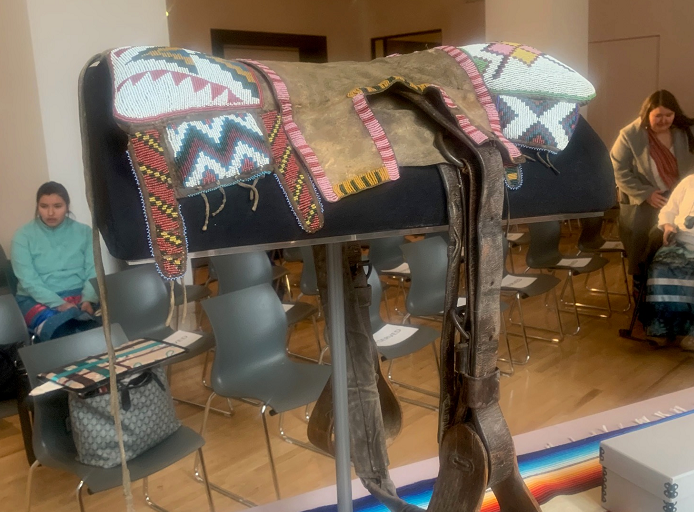

The museum acquired the two items nearly a century ago. The saddle is made out of tan hide and adorned with beads in colours ranging from red, yellow and green. The museum said the item was sold to them in 1924.

The ceremonial pipe is dark in colour and made out of ceramic or stone. Like many First Nations customs objects used in ceremony, the pipe cannot be photographed. The museum received it in 1936.

The family has been working with the museum since September 2022 on how best to return the items.

The museum provided special packaging and carrying cases to ensure objects are safely transported. In some cases, museum employees may offer recommendations for how something can be stored or exhibited, but what is done with the items afterwards is entirely up to each individual community, said Huaco.

“Repatriation means genuinely turning these objects back over to the ownership of originating nation, which means that the museum doesn’t dictate anything about the future care or display.”

Huaco added there has been a steady increase in repatriation requests, with the museum averaging about 20 requests per year. She said the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report in 2015 played a role in empowering Indigenous communities to take a more assertive role in identifying objects that could be returned to them, and museums have become more responsive to those calls.

Part of this includes examining work within the museum as well.

The institution temporarily closed its gallery dedicated to First Peoples art and culture last year to work with Indigenous museum professionals on what they called critical changes to the gallery.

There was no one event that lead to this, said Huaco. Instead, the museum wanted to shift to have Indigenous voices be the decision makers in how content is exhibited.

“It isn’t a sort of black and white change. It’s a continuing gradient of change in which the voice of authority is recognized,” said Huaco.

Poundmaker, whose Cree name is Pitikwahanapiwiyin, is considered one of the great Indigenous leaders of the 19th century and was key in negotiations that led to Treaty 6, which covers the west-central portions of present-day Alberta and Saskatchewan.

A number of the leader’s belongings were taken and housed in museums after the Northwest Rebellion in 1885 –same year Poundmaker was convicted of treason for leading his warriors in the battle against Canadian Forces after government soldiers attacked about 1,500 Indigenous people, including women and children. He served seven months before dying shortly after his release.

Pauline Poundmaker says the growing movement of institutions repatriating items shows there is a willingness to address previous harms against Indigenous Peoples.

“It’s a beautiful shift to having different relationships and writing a different history,” she said.

The family hopes to open a museum dedicated to the leader in a yet to be determined location. Until then, the items will be placed in safe keeping, Pauline Poundmaker said.

She has been told there are about 20 other items spread across North America and Europe. The family is in the beginning stages of getting two other items repatriated.

“We want to continue to preserve our history and honour history,” she said.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.