The overall inflation picture is improving for many line items on Canadians’ household budgets — with at least one notable exception.

Fresh data from Statistics Canada released Tuesday shows the price of food continues to soar, even as the headline inflation figure ticked down at the start of 2023.

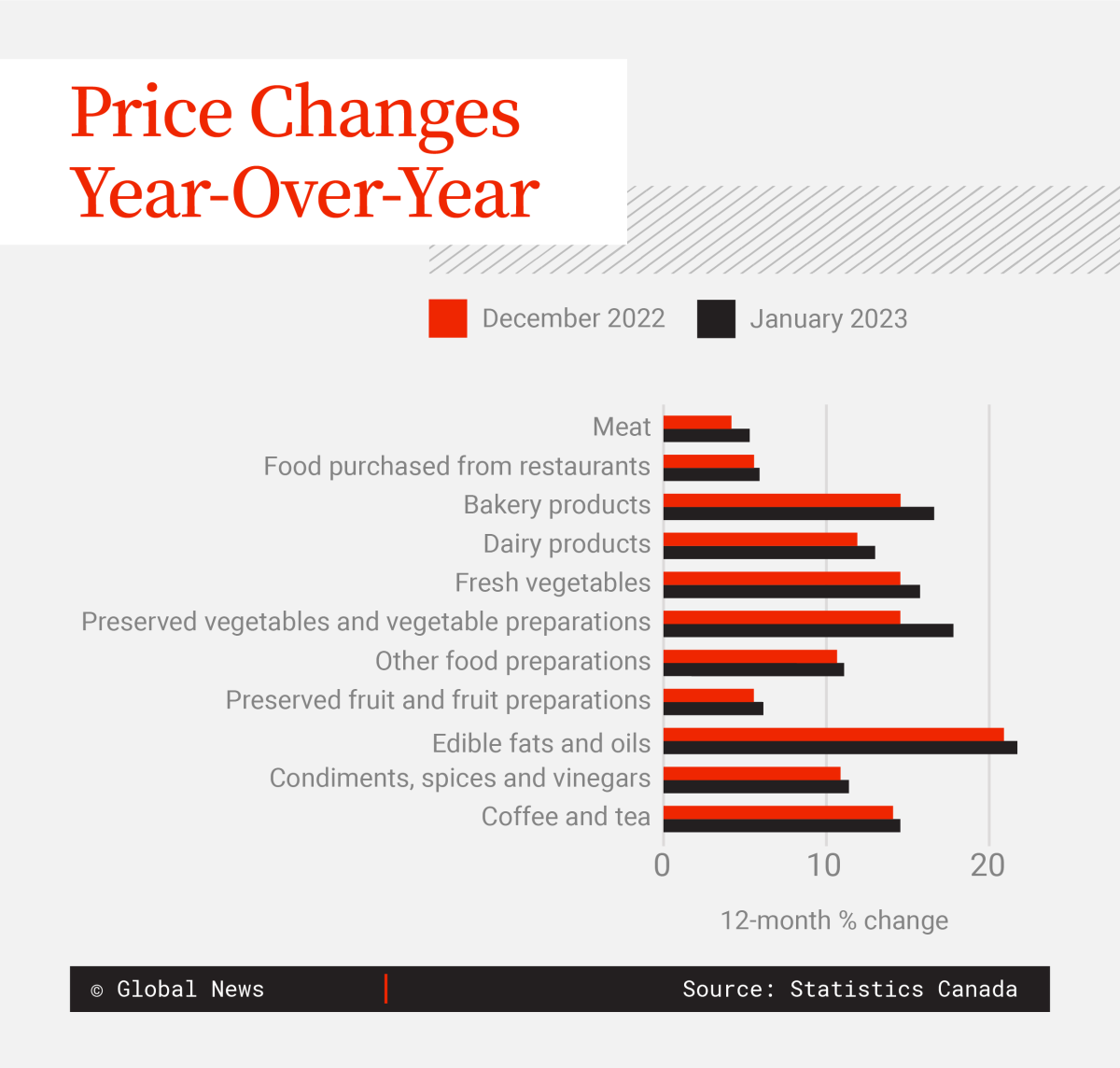

The agency said food prices were up 10.4 per cent year-over-year in January — up slightly from December — while the rest of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) items decelerated to an annual pace of 5.9 per cent.

Food inflation has outpaced the general inflation rate for 13 months in a row. And while StatCan’s CPI tracks a representative basket of goods to show general trends in Canada, Sylvain Charlebois, director of the Agri-Food Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University, says consumers might find their personal inflation rate is even higher if their diets are made up of the fresh foods and grains that are being hit particularly hard.

“I suspect a lot of people are saying, ‘Well, 10.4 per cent is unbelievable. Well, they’re right. Actually, it’s probably more than that,’” he says.

January’s grocery store prices were higher for meat (up 7.3 per cent), bakery products (up 15.5 per cent), dairy (up 12.4 per cent) and fresh vegetables (up 14.7 per cent).

There were some aisles of relief, however: lettuce, specifically, saw a 5.8 per cent price drop last month, as did oranges (down 1.8 per cent), pasta (down 0.5 per cent) and breakfast cereals (down 2.9 per cent). Fish — be it canned, fresh or frozen — also saw some modest price drops.

Why is food inflation still so high?

Statistics Canada pointed to a few global factors driving up food prices. When it comes to chicken, which saw costs rise 9.0 per cent year-over-year in January, the agency pointed to avian flu outbreaks, strong seasonal demand and continued supply chain issues as fuelling the price hikes.

Charlebois says nearly a year after the war in Ukraine began, the conflict is still stymying access to grains and other inputs from the region. Lingering supply chain constraints are making it more expensive to source and ship ingredients, driving up costs for producers, processors and retailers alike, he says.

Get weekly money news

“All of these things are just creating more sticker shock moments at the grocery store.”

But with production disruptions easing, Royal Bank of Canada Economist Nathan Janzen said food inflation should start to slow. He said the bank’s latest forecast shows it dipping below three per cent by the end of 2023.

“We are expecting growth in those prices to plateau and … and we are starting to see some signs of that,” he told The Canadian Press.

“Year-over-year price growth in grocery prices is still extremely high, but it’s been kind of flattish since last fall. What we’re seeing is probably still, at least in part, the impact of those earlier global supply chain disruptions, transportation disruptions, as well as spikes in agricultural commodity prices earlier last year and those shocks have unwound to an extent.”

Janzen cautioned that Canadians shouldn’t expect to pay less for their groceries in the near future.

“It’s easier for prices to go up than down,” he said. “We’re not expecting prices to decline, just to grow at a slower rate.”

Charlebois agrees that Canadians hoping for a break this month or next might be disappointed. A Feb. 1 hike to farm gate prices on dairy in Canada means these costs will likely continue to rise in future CPI reports, for example.

Canadians are in for a “rough winter,” Charlebois says, though he anticipates food inflation will return to more typical levels in the spring and summer months.

Calls grow for more grocer competition, transparency

A House of Commons committee studying inflation last week summoned the CEOs of Canada’s big three grocers — Empire Co. Ltd., Metro Inc. and Loblaw Co. Ltd. — to answer questions on the causes of food inflation.

Executives from all three companies have testified at past committee meetings focused on the rising cost of food — but not their CEOs.

“Those at the heads of these companies, where the buck stops, should at least have to answer questions around why their profits are so high and why their prices are so high,” NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh said last week. “And why are they profiting off the backs of Canadians?”

In response to online criticism from consumers, Loblaw acknowledged recently that it has become the “face of food inflation,” but also claimed it makes less than $4 of profit on every $100 grocery bill.

If these CEOs do appear, Charlebois says the committee ought to focus its questioning on breaking down sales in their stores more clearly than they do in their financial statements. Currently, it’s difficult to break out whether revenue growth comes from food sales or cosmetics, clothing and pharmacy divisions, he notes.

“The information that we get is very sketchy and unclear,” Charlebois says. “I would actually try to dig as deep as possible into the data with CEOs in the room, or else it’s just a waste of time.”

Regardless of the CEOs’ answers on the causes of food inflation, Charlebois says Canadian consumers would benefit from more competition in the form of discount grocers such as Aldi and Lidl elsewhere in the world.

While Canadian grocers’ profit margins have stayed largely consistent through the current inflationary period, those margins are roughly double what’s reported from their U.S. grocery counterparts, Charlebois notes.

A Senate of Canada report delving into inflation released last week highlighted the need to increase competition in Canada in an effort to limit price pressures in the long term.

“We need more competition. We need a discount grocer in Canada,“ Charlebois says. “We need a market disruptor.”

— with files from The Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.