As Canada continues to witness violence on public transit agencies in some of its major cities, there are calls to increase resources and support towards social crises, including mental health, addictions and homelessness, all of which have been exacerbated as the country recovers from the pandemic.

In Toronto, Mayor John Tory has demanded a national health summit that includes all levels of government to address these concerns and discuss possible solutions for those struggling. Tory has blamed upper levels of government for a lack of funding for municipalities and said the lack of spending is “painfully clear on the streets” of cities across the country.

According to data from the city based on shelter system intake, there are more than 10,400 people who are currently experiencing homelessness. More than 1,200 individuals were newly introduced into the system last December alone.

Global News wanted to get a better understanding of the unique challenges individuals are currently experiencing, so staff tagged along with a non-profit doing evening outreach to those who were either experiencing homelessness or on the brink of living precariously.

Jody Steinhauer runs a business, Bargains Group, and a charity, Engage and Change. Her business makes winter survival kits, while the charity is well-known for its annual program Project Winter Survival, which works with volunteers, businesses, front-line social agencies and homeless shelters to distribute the supplies to those in need. Seeing the homelessness crisis worsen over the years is what has motivated Steinhauer most to take matters into her own hands over the last two decades.

“We started Engage and Change 24 years ago because we deal with the homeless shelters every single day and when we saw the disparities between budget and need, we thought, ‘This is crazy and we’re business people so we can do something about that,’ so we just reached out to like-minded people like ourselves and said, ‘This is wrong, this is our community,'” said Steinhauer.

As the sun begins to set on a cold January evening, Steinhauer and her team are assembling kits at the Engage and Change Headquarters, which they plan to hand out later that night. There’s a pile of sleeping bags that will soon be loaded into the outreach van. They stuff backpacks with the fundamentals: hats, socks, scarves and gloves, snacks, water and essential hygiene supplies. Staff also throw in stress balls for circulation, a deck of cards to stimulate the mind and a pen and notepad for folks to write down notes or important phone numbers. Lastly, a message of hope written personally by each team member is placed into every kit. One of them reads: “You are worth it.” Another says: “Dream Big.”

“We don’t want people to die, and we know these kits are saving people,” Steinhauer told Global News.

“Homelessness is way, way worse. And now there’s a bigger problem: there’s no shelter beds this season. People are sleeping in parks and encampments and the (pandemic) hotels that were there to help them are closing down. We’ve got an epidemic.”

After loading dozens of winter survival kits into the van, Steinhauer and her team drive to their first stop at a Loblaws parking lot near St. Clair and Bathurst Street. It’s dark outside. The vehicle pulls up to dozens of folks, who appear to have been waiting eagerly in anticipation of community outreach staff.

Social workers with an affiliated non-profit, Ve’ahavta, also arrive on scene to hand out food as the Engage and Change team gives out its winter survival kits. Moments after, the doors swing open, and people gravitate toward the vans and quickly form a line to receive the items.

Robert

Among the group of people in the Loblaws parking lot is Robert, who is in his 60s. He is one of the first individuals who agree to do an interview with Global News. Due to safety concerns, Global News has chosen to identify those we interviewed only by their first name.

We ask Robert about his current living situation and why he’s using outreach services.

Get breaking National news

He tells us he currently lives in a private boarding home in Toronto.

“There, the rent is nearly a thousand dollars. I had difficulty finding a cheaper place, but I’m glad I’m housed. They’re helping me a lot. I work for the landlord doing odd jobs,” he said.

“I used to be a welder. I welded government-inspected hot water tanks. I also worked as a former copy technician, worked in a restaurant delivering food, worked in a tea plant, worked as a security guard and worked as a lifeguard … in addition to many other jobs.”

Despite a long resume of previous jobs, Robert’s current mental health challenges have made it difficult for him to find and retain work.

“I have schizophrenia. When I got it initially I heard voices, saw visions. They took away my driver’s licence, but I can get it back by re-testing. But since I have no job, I handle stress very poorly. I’m 60 years old and I’m practically retired, so no one’s really interested in hiring me,” he said.

“These people (here), they work. They have jobs. It’s not like they don’t work.”

When asked if he was getting enough mental health supports, Robert told us that while he was appreciative for the help he was currently receiving, getting housing was his largest hurdle.

“I find that I’m getting some of the supports, but there’s still difficulty in finding proper housing which is affordable in Toronto. I’ve been looking for years. I was housed in another place but I left because they had some problems there. There was a guy there who used to threaten to kill me.”

Kerry

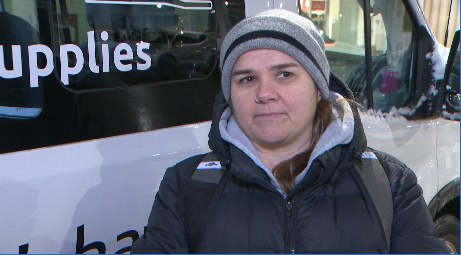

Kerry is in her 50s and currently living low income. She was also among those using the charities’ services.

“It helps me because I’m on ODSP (Ontario Disability Support). I do have a place but the rent is really high and I’ve been waiting for housing for a really long time and it’s just me so every little bit helps. I also use a lot of other services as well, like other food places around the city,” she told Global News.

“It really makes it a lot harder to live when you don’t have much money to live on.”

Kerry says she has been waiting six years for housing.

“I keep calling them and checking in, but they keep telling me I have to wait.

“I used to live on the streets myself…. I did two summers and two winters and I’m glad I’m not doing that anymore … so I feel for the people that are actually homeless. A lot of them are my friends too.”

Tom

Tom currently lives near a ravine in the area. He says for him, homelessness was a choice.

“I’ve been living off the grid for the last six years and it’s a spiritual journey for me. I basically gave up everything. My job, my apartment, everything. I was living in a Subaru Forester for three and a half years before it was stolen. And then I was on the streets,” he said.

Tom has since been using all resources and supports available to him.

“I basically have been navigating the bottom of the system. The Out of the Cold-type programs, the Ve’ahavta programs, the housing system.”

“For me, homelessness was a choice and now it’s difficult to get back into the system because how do you afford rent? I’m on a disability now because I have osteoarthritis. (These programs) are really essential because you’re not getting the support from government. There’s no political will to do anything about the situation.”

As someone who has been experiencing homelessness for years, Tom says he has been keen on observing what’s going on around him.

“Everything is some sort of dysfunction, and the number of people who are self-medicating…. Once you start down that road, you lose yourself.”

As the crowd clears out of the parking lot after receiving food and survival gear, Steinhauer and her team get back into their van and head to their second stop at Queen and Sherbourne streets. They stop outside of the Maxwell Meighen homeless shelter. The streetlights shine light on the icy, snow-covered sidewalks.

Within minutes 30 to 40 people flock to the van, where Steinhauer and her team are distributing sleeping bags and kits. The vehicle is emptied out in less than 15 minutes.

A young woman immediately opens her backpack and puts on the hat, scarf and gloves. She appears to be struggling to keep warm amid the plummeting temperatures.

Scott Mills, a former Toronto police officer who volunteers with the non-profit, asks the woman if she has a place to sleep. She tells him she has just gotten out of the hospital.

“Probably not,” she says. “When I was at the hospital, I asked them to help me get to the woman’s centre and they didn’t. They didn’t help me get to the woman’s centre. They didn’t help me get anywhere.”

She tells the outreach team that she is going to ask a friend living in the area if she can stay on their couch.

Nasir

Nasir is sitting in a mobility scooter staring blankly into the empty streets before his eyes. He agrees to speak with us briefly. He says he’s been in the shelter system for a couple of years.

“I’m almost there to get a place, so hopefully soon,” he says without conviction.

“It’s kind of rough. I’ve been through it all my life, so I just kind of stay here for the moment. We have to go out and about in the morning and then go back at night time.”

Like many of the individuals we saw that night, Nasir didn’t have a winter jacket. He sat outside, braving the cold in a navy sweater.

“I get used to the weather. That’s how I live.”

He tells us he spends his days sitting in Tim Hortons, coming back to the shelter in the early evening and sleeping.

After we speak with Nasir, the woman who previously said she was going to try and sleep on her friend’s couch for the night returns to the site, sharing an update with Mills and Steinhauer.

“She just came back 10 minutes later and said, ‘S–t went down and they won’t let me sleep on the couch. I don’t know what I’m going to do,'” Steinhauer tells Global News.

Steinhauer then gives the young woman a pre-paid Visa card she had with about $200 and tells her to get a hotel. She then embraces the woman tightly in a mother-like hug and wishes her well. She watches emotionally as the woman walks alone down Sherbourne, eventually fading into the darkness.

“She was a mess. This should not be happening in our city. We just desperately need housing and if these people, if they can just get a roof over their heads to start out with and get some social services around them.”

Mills echoes Steinhauer’s thoughts and shares his perspective on the situation as a former constable.

“People go to their neighbourhoods and they don’t have to come and look at this. But if you’re working down here as a first responder, whether you’re a paramedic, fire department, police officer or all of the amazing outreach teams that are out here … they’re trying. But there’s just not enough places. The addiction, the alcohol and the drugs are a big factor,” he said.

“Lots of times as a cop you pick somebody up that’s really in trouble. They’re high or they’re drunk. You don’t want to take them to a cell. You try to bring them (to a shelter), they’re full. For that woman there is she had an addiction problem, it would be really hard to find a spot for her.

“I don’t know what the answer is.”

In a statement emailed to Global News Monday, a spokesperson for John Tory said the mayor “understands that a lack of mental health supports contributes to a number of issues we are seeing in cities across the country – one of them being homelessness.”

The spokesperson said Tory called for a national mental health summit last week, adding that the mayor received widespread support from mayors across Ontario.

“Conversations are ongoing regarding the summit,” the statement read. “We have heard from a number of mental health organizations and groups that are supportive of the Mayor’s advocacy and he will be talking to them and meeting with them in the days and weeks ahead.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.