Many people have been asking me why there’s been so much talk about atmospheric rivers over the last few months. Aren’t they just the same old rainstorms we’ve always had?

Yes, major rainstorms have always made landfall on the West Coast. It is a rainforest, after all. What has changed is the frequency, size and impact of these rainstorms. The extreme rains and washouts of fall 2021 in B.C. demonstrated this with great devastation and cost.

The term “atmospheric river” is one tool meteorologists are beginning to use to better warn a region about the potential impact of an incoming system.

What is an atmospheric river?

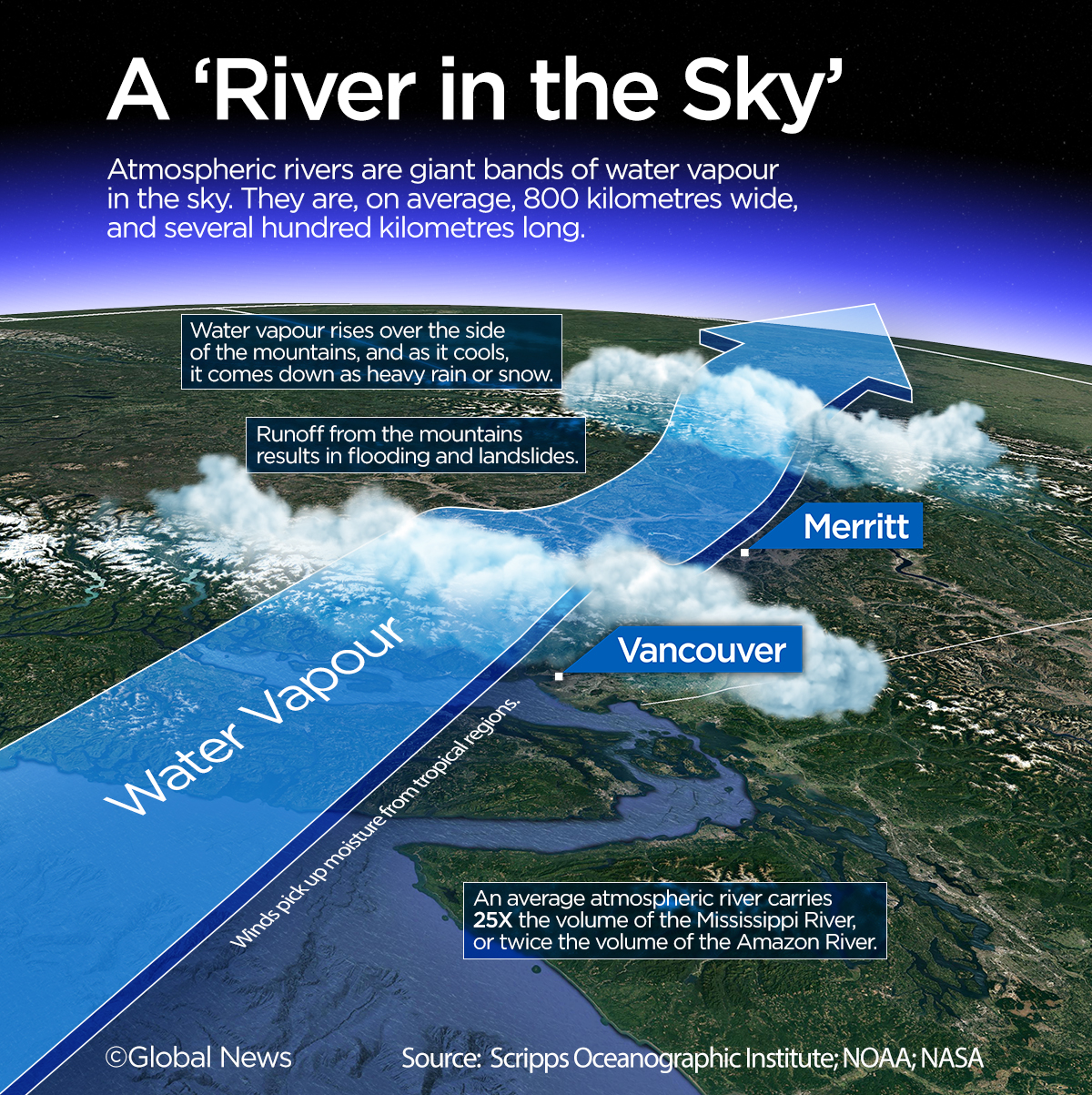

An atmospheric river is a long, narrow band of concentrated water vapour in the sky.

They are the largest “rivers” of fresh water on Earth, transporting on average “more than double the flow of the Amazon River,” according to the Glossary of Meteorology.

They are typically 800 kilometres wide and 1,000 km long.

These weather systems travel from the tropics toward the poles through the mid-latitudes where they encounter the west coast of North America. One or two dozen atmospheric rivers can make landfall each year.

Have you heard the term Pineapple Express? That’s used to describe an atmospheric river that originates near Hawaii.

When these moisture-laden systems encounter mountains, heavy rain is forced out of the river as they push up and over in a process called orographic precipitation.

These periods of heavy rain can last days if the atmospheric river stalls over one area and can produce more than 90 per cent of the extreme rainfall along the B.C. coast.

While atmospheric rivers play a crucial role in the global water cycle and help replenish reservoirs, they can also generate devastating floods and debris flows.

Where did the term come from?

The term “atmospheric river” was first coined in a research article by two scientists, Yong Zhu and Reginald E. Newell, from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1998.

In the early 2000s, the term began popping up in research papers around the world. Scientists were seeing the storms’ impact and realizing the need to better understand the dangers they bring and the potential benefits.

Starting in 2010, as our climate changed, the number of research articles on the subject accelerated. Atmospheric rivers were causing more major floods around the world, especially along the west coast of North America.

Marty Ralph is a pioneer researcher on the topic as the director of the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes in San Diego. His team began flying the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Gulfstream IV jet, a specialized hurricane aircraft, into the rivers to better estimate the size and severity of incoming systems.

His team was also the first to begin categorizing atmospheric rivers — a key step in creating an alert system for regions along the U.S. coast.

“Scales for meteorological phenomena, such as hurricanes and tornadoes, have proven very useful in raising public awareness of potentially hazardous conditions. Atmospheric rivers (ARs) are the most impactful type of storm that occurs along the West Coast and are a major source of extreme precipitation,” the San Diego centre explains.

In B.C., research on atmospheric rivers has also accelerated.

“Every year since 2001, BC has experienced a significant flooding event caused by extreme weather or precipitation, and the impact of these events was significant,” says a report summarizing a 2013 atmospheric river workshop hosted by the Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium alongside the B.C. Ministry of Environment.

Here are some examples:

- An extreme storm event in January 2009 lasted two days and cost nearly $16 million

- A two-day event in June 2011 resulted in flooding with costs in excess of $85 million

- In 2012, 15 flood events affected more than 100 communities in B.C.

- In fall 2021, a massive two-day event resulted in five lives lost and massive floods, washouts and landslides. Highways and railways into the Lower Mainland were damaged, cutting the region off from the rest of the country. This was the costliest natural disaster in B.C.’s history.

How is climate change affecting atmospheric rivers?

Toward the end of this century, estimates suggest atmospheric rivers will likely be about 25 per cent longer and 25 per cent wider, and will transport about 50 per cent more water vapour. The impact on the B.C. coast is expected to be significant.

A recent study by Environment and Climate Change Canada suggested the probability of an atmospheric river with the same amount of water vapour as in B.C. in the fall of 2021 is now 60 per cent more likely because of the effects of human-induced climate change.

The study also said the probability of a one-in-100-year streamflow event, which leads to washouts and flooding, has increased by 120 to 330 per cent from October to December.

How will an atmospheric river scale help warn the public?

Meteorologists and governments have been using the term “atmospheric river” more often in order to better communicate the impact of an incoming rainstorm. The ability to differentiate between a standard rainstorm and one that could devastate a region has become essential.

Researchers like Ralph’s team in the U.S. have known this for years.

The atmospheric river scale they created uses two criteria to classify events: intensity (the amount of water vapour the storm transports) and duration (the amount of time a storm will impact a certain region).

The definition of their categories are as follows:

- Category 1 AR – Primarily beneficial

- Category 2 AR – Mostly beneficial, also hazardous

- Category 3 AR – Balance of beneficial and hazardous

- Category 4 AR – Mostly hazardous, also beneficial

- Category 5 AR – Primarily hazardous

These categories help notify the public when they should be preparing for hazardous conditions or when an atmospheric river will perform more like a good old rainstorm and actually help the region.

Nearly one quarter of the water supply in the Pacific Northwest is transported by atmospheric rivers. They help fill reservoirs and build the much-needed snowpack for the summer months’ water supply.

In Canada, the federal government has begun using the term “atmospheric river,” but has not yet adopted a national scale.

B.C. Public Safety Minister Mike Farnworth urged Ottawa to implement one in the wake of the fall 2021 storm, which has been estimated as a Category 4 or 5 atmospheric river on the U.S. scale.

In response to a recent inquiry from Global News, Environment Canada said the rating system doesn’t capture many factors that lead to flooding and damage, such as the quantity of snow in the mountains, moisture in the soil from recent rains, and the amount of water in reservoirs.

“Environment and Climate Change Canada applied scientists are investigating new formulations of an Atmospheric River rating scale to see if they can incorporate some of the other important impact factors, however this work is still at a research stage,” the ministry said in an email.

An analysis of B.C.’s 2021 atmospheric river event by Environment Canada and the Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium shows the impact was exacerbated by the state of the local terrain.

Also, the region had an above-average recent early-season snowpack. This snow melted quickly under the warm, heavy rains of the atmospheric river, adding to the immense runoff coming down the mountains.

Although the analysis showed no apparent relationship between the percentage of an area burned and its runoff efficiency, the report states they “cannot rule out a possible influence on runoff efficiency in these basins.”

Comments