As Ukraine continues to battle through attacks nearly eight months into Russia’s invasion, a Western University professor is working with a team in the development of a school-based mental health program for Ukrainian children fleeing the war.

Since February, researchers estimate roughly 130,000 school-age children have entered the Czech Republic from Ukraine, reportedly suffering from “varying degrees of psychological distress” due to the invasion.

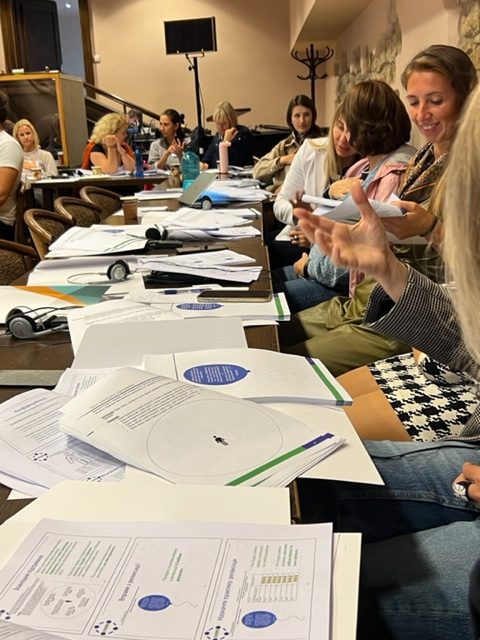

Claire Crooks, director of Western’s Centre for School Mental Health (CSMH) recently went to the Czech Republic for five days to train social workers and psychologists in STRONG (Supporting Transition Resilience of Newcomer Groups).

Crooks, along with Sharon Hoover of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, and Dr. Jeff Bostic from Georgetown University, shared details of the program during their travels with 34 professionals from over 20 different organizations.

“It really hit home for me that 10 of the folks we were training were actually Ukrainian psychologists who had fled Ukraine,” she said. ” So, they’re there as psychologists and trying to support Ukrainians in Czech Republic, in Ukraine, and all over the world, and yet they’re there as mothers, family members and trying to get their own children settled.”

Crooks highlighted the mental health effects of war alone can have on a child, explaining the difficulties it can have on their school attendance, learning and social adjustment.

“Fleeing war is not a normal childhood experience,” said Crooks, who is also a professor in Western’s Faculty of Education. “Children are developing self-regulation, coping skills, and problem-solving all through their childhood, you develop these capacities, but something like what these kids are going through just totally overwhelmed them.”

She explained that STRONG provides effected children with a toolkit that works from a “strengths-based perspective” to help them cope with stress while simultaneously building those important problem-solving and goal-setting skills through 10 available sessions.

“They also have an opportunity to work one-on-one in a session with a psychologist or social worker and tell their story or a little bit about what they’ve gone through,” Crooks said. “So, in addition to the skills, they really get a sense of connectedness with other youth and recognize that other youth have gone through very similar things.”

She said that the hope is that the trainees will spread and teach the program to their colleagues, both in schools and community groups in helping traumatized children and teens. Adding that it’s not typical for professionals to be trained in such a short period of time, but that it’s essential that Ukrainian children get the support they need as soon as possible.

Get breaking National news

According to Crooks, STRONG was developed in Ontario back in 2017, through partnerships with U.S. colleagues, to support Syrian newcomers, as well as other newcomers to Canada.

She said that for a number of years, her team has been “implementing and evaluating” the program across the province. However, using it to help Ukrainian newcomers, Crooks said that it’s different this time around.

“I think what’s new about it is how quickly people are trying to insert mental health support,” she said. “We’ve often sort of thought that we’ll deal with the mental health later, we need to get family safe, we need to get people fed and housed, which, of course, are very important issues. But I think what strikes me is that this time, there’s also that recognition of the importance of mental health.”

Crooks added that while providing mental health support for kids, adults, in these situations, are experiencing the same levels of trauma as well.

Since leaving the Czech Republic, Crooks said that the team is sorting out the last little bit of the implementation plan before the program is utilized.

“Setting becomes especially important when your entire life has been disrupted and it helps kids start to look towards the future,” Crooks said. “It’s about helping children how to understand and process their feelings and reactions which is crucial for their development.”

— With files from Global News’ Devon Peacock

Comments