As Canada continues to grapple with a nationwide labour shortage, some workers say it’s happening because people are less willing to work for low pay and poor treatment.

Last fall, Ben Coleman decided to leave his job at a Halifax-area grocery chain due to a “culmination of things,” with low wages playing a big role.

“Had there been better wages or better benefits, it might have given me reason to stay, but I just felt I would have been better suited elsewhere,” said Coleman, 22.

There were times, he said, where – between balancing rent and other bills – he had difficulty affording food, and his friends and co-workers would give him some.

Other times, when he was doing a little better, he would do the same for them.

A bit ironic, said Coleman, considering he worked at a store that sold almost nothing but food.

“People need to get fed, but the people working there also need to have food on the table,” he said.

The skyrocketing cost of living, especially in recent months, is making it increasingly difficult for Canadians to get by.

The consumer price index rose 7.7 per cent in May compared with a year ago — its largest increase since January 1983, when it rose 8.2 per cent. But the cost of food continued to outpace overall inflation, rising 9.7 per cent compared with a year ago.

For reference, Nova Scotia’s minimum wage has risen by three per cent – to $13.35 – since last year.

Meanwhile, grocery companies are further widening their profit margins.

In its latest quarter, Loblaw, which owns Superstore and No Frills, among others, saw net earnings rise nearly 40 per cent compared with last year to $437 million, while sales rose just 3.3 per cent to $12.26 billion for a profit margin of 3.56 per cent — up from 2.68 per cent in 2021.

Empire, which owns Sobeys, Safeway and FreshCo, among other brands, reported a quarterly profit in March of $203.4 million, up 15.4 per cent from $176.3 million a year earlier. Its profit margin compared with sales, which rose by just 5.1 per cent, climbed from 2.51 per cent last year to 2.75 per cent.

Coleman, who now works at a bar, questions why companies making record profits aren’t paying more to the workers on the ground who play a big role in bringing that money in.

“It’s just kind of absurd that there’s a lot of people working for these huge corporations that aren’t able to feed themselves or have proper housing, but yet the people on the top are doing the best they ever have,” he said.

“If we truly are essential, then we deserve to be treated and paid like we are essential.”

One million job vacancies

According to a report released by Statistics Canada last month, the number of job vacancies at the beginning of April hit just over one million, up more than 40 per cent compared with last year.

The agency said employers in Canada were actively seeking to fill 1,001,100 vacant positions, up 23,300 from March of this year and a gain of 308,000 compared with April 2021. In Nova Scotia there were 20,000 vacant positions, which is actually a decline of nearly 3,000 from the previous month.

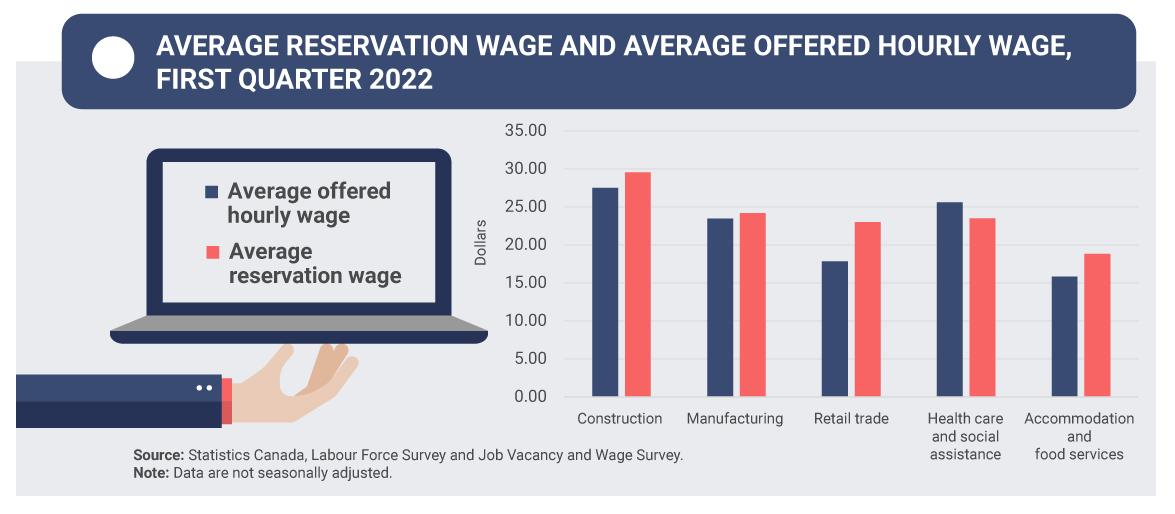

The sectors hardest hit by the labour shortage are construction, manufacturing, retail trade, accommodation and food services, and health care and social assistance.

Statistics Canada said “mismatches” between the offered wage of these jobs and the reservation wage – the minimum hourly wage at which job seekers are willing to accept a position – “may be contributing to the elevated level of job vacancies in certain sectors, particularly in retail trade and accommodation and food services.”

Get daily National news

In retail trade, Statistics Canada said the average reservation wage is $23, but the average offered hourly wage is $17.85. In accommodation and food services, the average reservation wage is $18.85, with an average offered hourly wage of $15.85.

The accommodation and food services sector has the highest job vacancy rate at 11.9 per cent. According to Statistics Canada, employers across the country were actively seeking to fill 153,000 vacant positions in April.

“This sector had the lowest average offered wage for vacant positions of any sector in the first quarter of 2022 at $15.85 per hour,” the agency said, “despite a larger year-over-year average offered wage growth recorded in the sector (+5.4%) compared with all sectors combined (+2.5%).”

The wage issue is a big one for Chantelle Comeau, who has worked for more than 20 years in the food and hospitality industry.

“I’ve worked everywhere. I’ve done hotels, I’ve done franchises, I’ve done standalones,” Comeau, 38, told Global News.

The industry has changed a lot over the years, she said, with one of the biggest being the quality of life for staff.

“(Back then) you could actually afford to work 28, 30 hours, maybe 35 hours a week, and afford rent and food, and if you had a vehicle, you could afford to run it,” she said.

“And now, not so much.”

‘I have bills to pay too’

Last year, Comeau quit her job working in the kitchen of a Halifax-area inn, where she was employed for about a year, saying it was “one of the worst places I’ve worked.”

When she first started, she said she was only offered $1.50 above minimum wage, despite her years of experience, and she had to deal with micromanagement and issues above her pay grade.

“It was basically a managerial job, without the title and without the money,” she said.

Comeau – who now works at a local pizza shop where she says she is treated and paid well – said lack of respect and lack of pay are both huge issues in the restaurant industry.

“Most of the places I’ve worked at, that’s all it’s been … ‘Shut up, do your job, make me money,’” she said.

“Where I’m at right now, it’s fantastic. It’s like, ‘Yeah, we need to make money, but also, we want you to be happy. We want you to be able to afford to live.’

“There’s no reason that employers can’t do it.”

Comeau said employers can’t underestimate word of mouth between employees. Some of the chronically understaffed restaurants in the city have developed “reputations” among workers, she said, resulting in fewer skilled people being willing to apply.

- Myles Gray had no definitive cause of death, but likely died of cardiac arrest: pathologist

- Artificial intelligence residency at Calgary Public Library raises some eyebrows

- ‘Where do we draw the line?’ Montreal real estate agent surprised over OQLF letter

- Ford government mulls legal changes to stop B.C.-style drug superlabs

“If you don’t value your staff, if you aren’t willing to pay your staff, you’re not going to find staff,” she said.

Currently, her former workplace has several job postings for both front-of-house and back-of-house restaurant positions, with advertised wages between $14 and $17 per hour.

Meanwhile, Comeau said her current job, where she makes a living wage, does not have issues finding or retaining staff.

“We’re fully staffed. We don’t have any issues,” she said. “We are constantly having people coming in trying to drop off a resume and we have to turn them away.”

Asked about business owners who are also struggling with the rising cost of living, Comeau said “there’s inflation for everybody.”

“I have bills to pay too,” she said.

“If you’re running a business that the margins are so minute that you can’t give your staff a living wage, maybe you shouldn’t be in business.”

The new normal

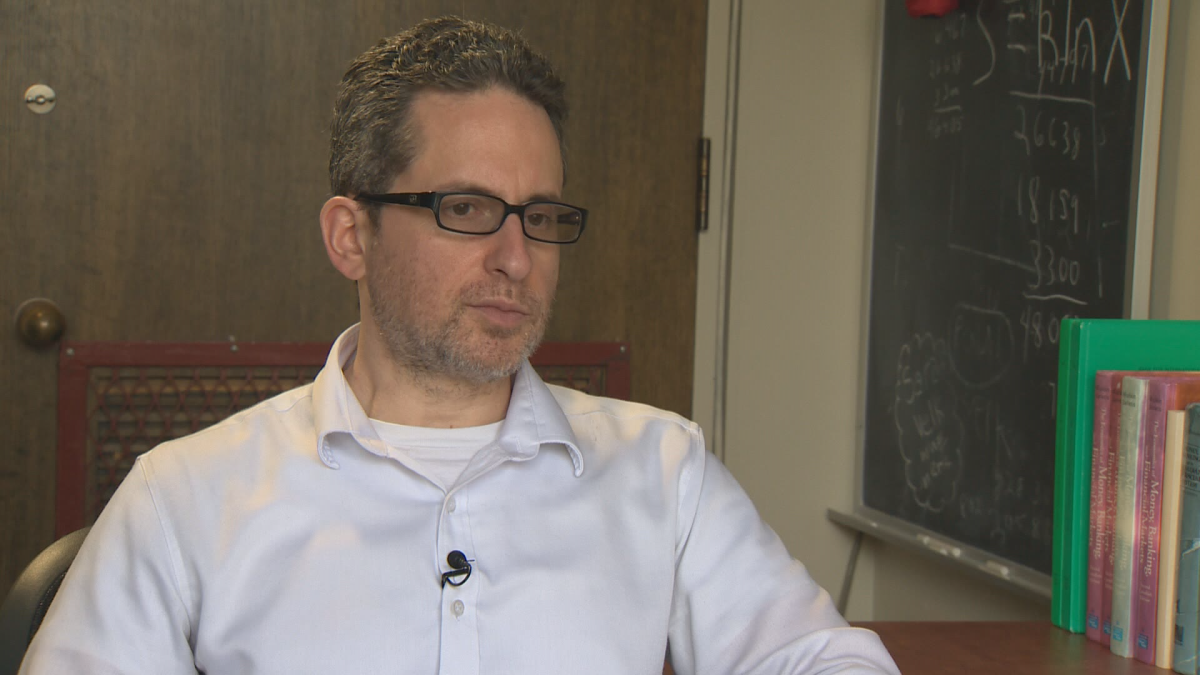

Moshe Lander, a professor in the department of economics at Concordia University in Montreal, said the labour shortage is “not going anywhere soon.”

He said the biggest driver has been COVID-19. People were “scarred” by lockdowns and social distancing, he said, and more than a year of CERB payments “did a lot to dull motivation.”

However, Lander said those entering the workforce are no longer motivated by just money.

“It used to be that if you couldn’t find people, you just increased the wage and that’s enough to get people out of the woodworks,” he said. “Now it’s more the work environment, and COVID really did a lot of damage to that.”

The pandemic made certain jobs – such as those that allow people to work from home – more attractive than others, he said.

“Whenever we go through a major event, there’s always going to be this shifting to the new paradigm, whatever that is,” he said. “The economy now needs to figure out, what is the new normal, and is it the way things used to be?”

Lander said while the labour shortage affects some industries more than others, nobody is immune.

He disagreed with raising the minimum wage, however, saying that would lead to businesses simply not hiring people and automating their jobs “out of existence.”

Asked why businesses are not automating now to address the labour shortage, he said that’s already happening, but would be hastened by a sudden wage bump.

“At some point, (automation) becomes cost-effective compared to a live human being,” he said. “The day is coming, it’s just when do they want to pull the trigger on that?”

Lander said the labour shortage is a long-term problem that will take a while to fix, and it’s important for all levels of government to look at the big picture of what the economy will look like years from now and begin teaching people marketable skills from an early age.

“This labour shortage is not something that’s going to be fixed by just increasing the minimum wage,” he said.

“It’s that there’s a fundamental rethink of the way society operates that needs to take place to create that sort of value in the labour market.”

‘A time of change’

Meanwhile, both Coleman and Comeau say they feel respected and happy with their new jobs.

Both said they’re encouraged by the issue of wages getting more attention, with Coleman saying workers now need to build on that momentum to demand better conditions.

“We’re in a time of change and we need to work towards an end goal that will be better for everyone,” he said.

Comeau said she hopes employers will realize that their employees will no longer stand for low wages and poor working conditions.

“A lot of places have just gotten in the habit of treating their staff like trash and just thinking they can get away with paying them nothing, and people are just going to take it,” she said.

“And with COVID happening and with CERB happening, people realize, ‘You know what, if I’m not going to get paid what I’m worth … then I don’t want to work for them.’”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.