Warning: This story deals with disturbing subject matter that may upset and trigger some readers. Discretion is advised.

A Ukrainian woman in Vancouver is grieving the recent death of her mother and sharing the story of the woman’s remarkable journey out of the besieged city of Mariupol.

Iryna Kuznetsova’s mother, Kateryna Kuznetsova, fled the war-ravaged city while fighting terminal cancer, buried her dead husband in her front yard, and escaped from Russian soldiers after being placed on a train “to nowhere.”

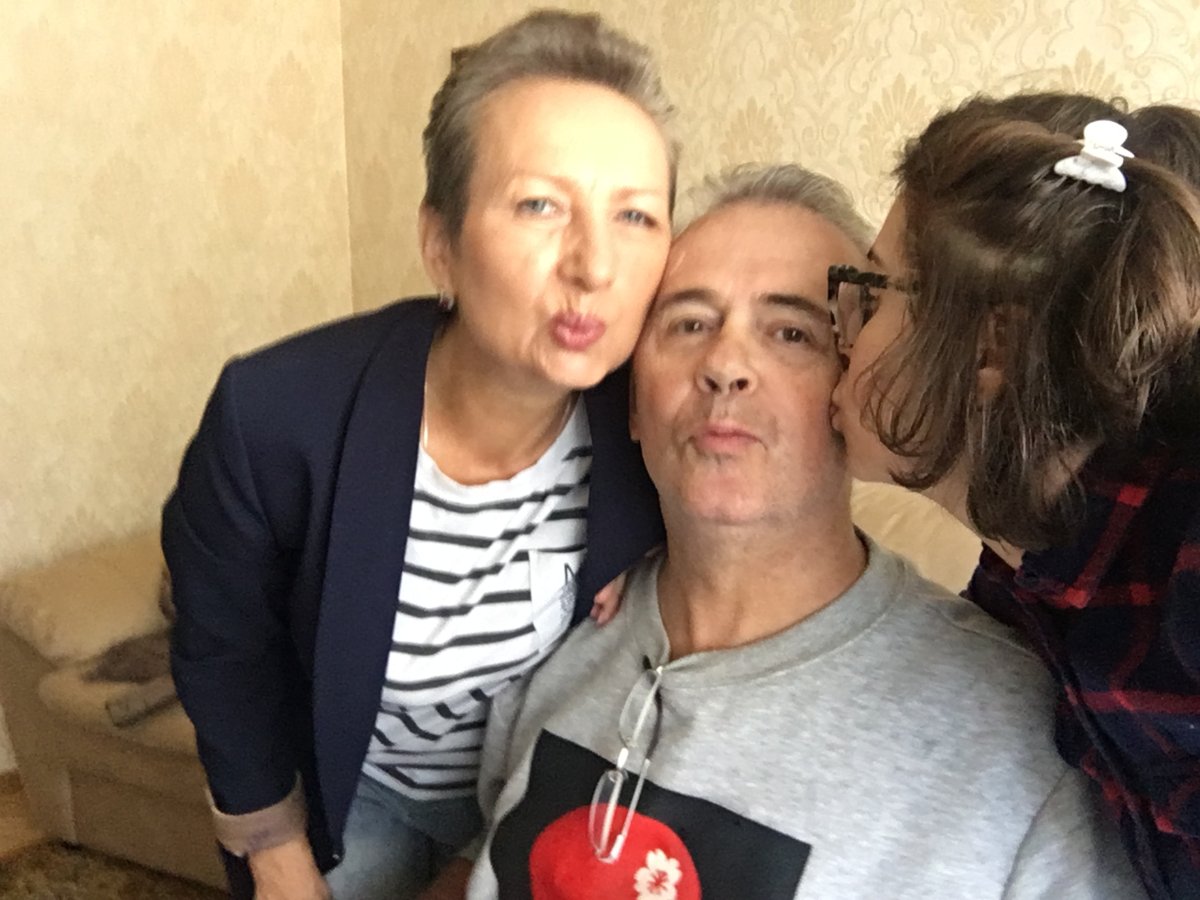

The two spoke to Global News from Kateryna’s hospital room in Tbilisi, Georgia, back in May, shortly after she made it across the border from Russia.

“After (my husband) died, I knew Iryna was waiting for me. I just couldn’t give up. It was not an option,” Kateryna told Global News in Russian, using her daughter as a translator.

“I put so much effort into (getting my) story out. … Many more people (need to) find out the situation Ukrainians are going through.”

After her mother’s death, Iryna said she still wants to share what her family has gone through, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine pressing on almost six months after it started.

“When you’re in Canada and the war is on another continent, it just feels distant, like when you watch a TV show. It just doesn’t feel real,” she said.

“But when you see someone – a real human, a real story – that you can relate to? It makes a difference.”

Mariupol encircled

Iryna, who came to Vancouver in 2013, suddenly lost contact with her family in early March when Russian forces completely surrounded Mariupol and began to take over.

The video game artist spent the next month at home in Vancouver, sleeping next to her phone, desperate for news of her family, as Russian forces slowly but surely squeezed the life out of her hometown.

“It was so weird, I felt so helpless. It was like I was watching my family be murdered online. You feel like you’re screaming, but you scream into the void,” said Iryna.

“Being in Vancouver, going outside, and seeing just normal life – when you’re not on your phone reading the news, your mind says it’s a bad dream.”

Terrified but determined to do what she could from a distance, Iryna attended local rallies in solidarity with Ukraine, constantly shared news coverage of the war on social media, and spoke to her friends in Canada to help educate them on what was happening.

As Mariupol was encircled and relentlessly shelled, its trapped residents had little to no access to electricity, heat, water, medicine, humanitarian aid, or telecommunications.

Kateryna and her husband, Oleksandr, who used a wheelchair because of a spinal cord injury, tried to wait out the siege in their apartment.

“I knew they would not be able to evacuate or go to the bomb shelter,” Iryna told Global News back in May.

“One of my biggest fears was that if anything hit the building and there was a fire, they could burn alive.”

- White Rock fatal stabbing suspect and victim may have been in physical altercation: IHIT

- High-profile B.C. sex offender Randall Hopley pleads guilty to 3 charges

- BC Hydro offers free AC units to lower-income, vulnerable customers

- B.C. to ban drug use in all public places in major overhaul of decriminalization

An estimated 22,000 Ukrainian civilians were killed during the nearly three-month stifling assault on the city, and Ukrainian officials have said thousands more bodies are feared buried in mass graves or strewn throughout the streets.

During the siege, Iryna was able to briefly make contact with her brother and his family before they fled to a safer part of Ukraine.

“The first question he asked me was ‘Are our parents alive?’ and I said ‘I’m so sorry, I don’t know,’” she said.

“We spoke for three minutes. Then at the end of the conversation, he told me he had to go, that the bombing had started. And I could hear it.”

She eventually found out through neighbours in Mariupol that her parents were still alive.

But days later, Oleksandr suffered a stroke. Russian soldiers ignored Kateryna’s pleas for help.

“My mom did everything she could, but there was no help,” said Iryna.

“He was dying the whole night.”

He died the next morning in the arms of his wife of 47 years. It was his 65th birthday.

Kateryna buried him in the front yard of their apartment building, marking the grave with a makeshift wooden cross.

Iryna’s brother is making arrangements to attempt to recover his body and arrange for cremation.

Fleeing Mariupol and the train to 'nowhere'

After laying her husband to rest, Kateryna offered to bribe Russian soldiers to help get her, the family cat, and a few belongings out of the neighbourhood. Complications due to cancer were making it hard to walk long distances.

The soldiers took her to a military outpost in the small, contested border town of Novoazovsk.

She was able to contact Iryna for the first time in three weeks and tell her about Oleksandr’s death.

“She told me that I couldn’t imagine what was going on in Mariupol, and what had happened – telling me about this, thinking, from her perspective, that I didn’t know,” Iryna said.

“She didn’t know I was searching every photograph, of all of the streets. They were so cut (off), they were pretty much left alone.”

From Novazovsk, soldiers brought Kateryna and several other civilians to Khartsyzk, an occupied city in the Donetsk province.

Kateryna described how they were brought to a filtration camp at a school, and fingerprinted, searched, photographed and questioned.

She had to block Iryna on Facebook for fear of being associated with any pictures of pro-Ukrainian rallies.

To carry only the essentials, she kept her cellphone but destroyed her iPad, for which she was reported to soldiers.

“They interrogated her and questioned her, assuming that she was destroying some sort of evidence,” Iryna said.

“Only when they saw that she had a bandage on her stomach area because of (her) tumor, they assumed that she was wounded and let her go.”

Next, Kateryna and many others were put on buses and asked where they wanted to be taken in Russia. She texted her daughter.

“I was like, ‘OK, who do I know in Russia? Who do I contact? I will go and contact everyone I know in Russia. I will do whatever. We’re going to collect her. We’re going to help her,” said Iryna.

Iryna told her mother to write down the city of Rostov-on-Don, about 2.5 hours from Khartsyzk, where she would arrange for an acquaintance to meet her.

The civilians had been promised they would be free to go once they were dropped off at their chosen destination.

Instead, they were brought to a small transit station in Taganrog, bordering Ukraine’s southeast, and made to get on unmarked trains with no indication of where they were going next.

“People were asking where it was going and the soldiers said, ‘To a nice place. You’ll be in a nice place,'” Iryna said.

After multiple redirections through Russia’s rural southwest over the course of several days, Kateryna confronted a train attendant as a last resort to get help.

“She told her, ‘Look at me, I have cancer. I’m going to die on your train and you’re going to have to deal with my body,’” Iryna said. “Only then did they realize that she was serious.”

Kateryna and her cat were let off the train at a random station in the middle of the night.

“I was feeling so unbelievably happy that I escaped, I can’t describe it,” she told Global News.

“The whole train was literally going to nowhere. I knew I needed emergency medical help. Where they were taking us, no one was waiting for me. No one was going to provide the help I needed.”

At the station, she traded her watch to a soldier for rubles and bought a ticket back to Rostov-On-Don, where she borrowed a stranger’s cellphone and called Iryna’s friend.

The friend brought her to a hotel, where she spent several days regaining her strength.

“She was the only one who left that unmarked train. The only person,” Iryna told Global News.

“She knew we were going to get her out of there. She managed to escape that train. I told her she’s my James Bond.”

Kateryna then traveled to the Russian town of Beslan, where her health deteriorated even more, and she was admitted to emergency care. The family cat died several days later.

Out of Russia

Kateryna was transferred to Vladikavkaz, south of Beslan, where she spent 22 days in hospital, then to a hospital in Tbilisi.

Iryna flew to meet her and was waiting at the hospital when she saw the car carrying her mother approach.

The driver took a wrong turn, so she rushed outside to call after them.

“I was chasing after her car. I think I was shaking the whole day,” Iryna said.

More than a month after leaving Mariupol, Kateryna had finally made it out of the war zone.

“I (wanted to buy) a big bouquet of roses and I asked my brother what colour I should get,” Iryna said. “He texted me a picture of her and dad with roses that he used to get for her. So I got those.”

Kateryna underwent emergency surgery to remove the fast-growing tumor, after a scheduled surgery in Mariupol was canceled in February, due to the war.

The surgery was not successful, and they were told Kateryna would not be able to travel to Vancouver, as the two had been planning.

“(We were told) we should stay in Georgia until the end (of her life). Which was heartbreaking. But the next day she started to recover, and they said she would be able to fly,” Iryna said.

“We started arranging to go to Canada. We wanted to fight for her life. Just coming to Vancouver to die was not a choice, after everything.”

'She knows I am strong'

They touched down at Vancouver International Airport on May 19 — one day before Ukraine’s Azov Regiment, the soldiers who made their last stand inside Mariupol’s shattered steel plant, finally surrendered and the city fell to Russia.

Kateryna was admitted to Vancouver General Hospital, where doctors again determined her tumor had grown too large to safely undergo surgery and she was too weak for treatment.

“It was one of the most challenging times in my life: On one hand, to be amazingly happy and grateful to have my mom with me, but at the same time, seeing the time, like sand, slipping through my hands,” Iryna recalled in an interview in early July.

“It is heartbreaking. But I didn’t have the opportunity to see my dad before he died. So I feel very grateful that I could have my mom here.”

Kateryna died in Iryna’s home in Vancouver on July 10 at the age of 66, after spending her final days talking with her daughter about their happiest memories with their family by the sea in Mariupol.

A former consultant for a construction firm, an avid knitter, and a talented cook, Iryna said she will also be remembered as a caring, courageous, and devoted mother.

Her ashes will be scattered 9,132 kilometres away from her husband and the home she loved.

“She showed me what true strength is …. One of the last things she told me is that she knows I am strong and she will always be there for me,” Iryna said.

She added that neither she nor her mother would have wanted to speak to media before the war.

“It’s not about us, it’s not even about our story. We are just telling this to help others. This is real people. It’s very important to see real people’s stories and struggles. The stories – they need to be real.”

Comments