Hamilton police are now incorporating virtual reality in their crisis intervention training with the goal of making officers better at de-escalating situations involving mental health crises.

The Mental Health Crisis Response Training Program (MHCRT) was created by researchers at Wilfred Laurier University and Toronto Metropolitan University, formerly Ryerson, in direct response to multiple reports on how police need better de-escalation training, including Paul Dube’s 2016 Ombudsman report and a 2014 report from Justice Frank Iacobucci on the police killing of 18-year-old Sammy Yatim on a Toronto streetcar.

Jennifer Lavoie, an associate professor of psychology and criminology at Laurier and one of the head researchers behind the program, said the training works like a “choose your own adventure” scenario where an officer is immersed in a virtual encounter with someone experiencing a mental health crisis.

“It’s really designed to do two things. The first is to allow officers an opportunity to recognize the signs of a mental health crisis,” she said.

“The second is to give them an opportunity through scenarios to practise de-escalation strategies, to learn and practise different kinds of communication techniques, and to practise relational policing approaches. And that will allow responses to be more humanized and safer over time.”

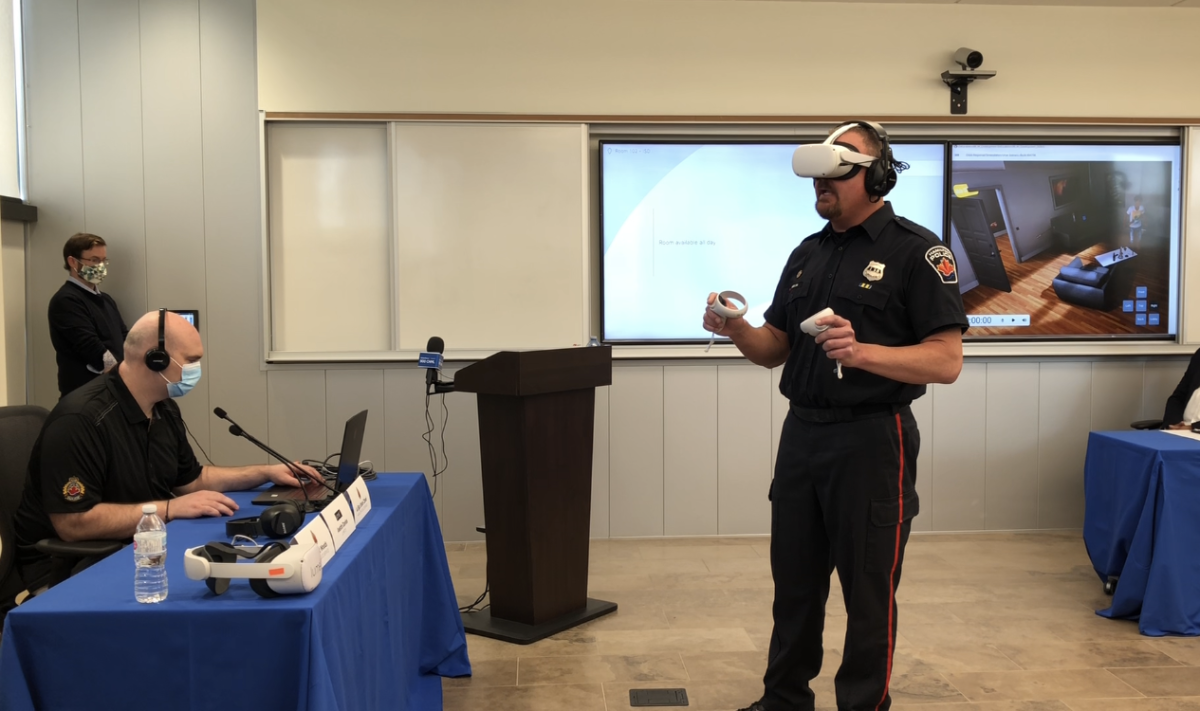

Const. Scott Woods gave a demonstration of the technology on Thursday, wearing the VR headset and interacting with a virtual person named Jamie who has PTSD and injuries to his face and ribs.

Woods spoke with Jamie, who had also just smoked pot, and learned that the young man was frightened of intruders coming into his home and attacking him.

At one point, Jamie picked up a bat, but Woods was able to speak to him calmly and reassure him that he was safe.

Get breaking National news

The simulation ended with Jamie putting down the bat and Woods calling paramedics to come by and check out his injuries.

Lavoie said the simulation could have gone differently if Woods wasn’t well-trained in responding to mental health crisis scenarios.

“We’re looking for officers to validate that concern and help Jamie feel safe,” she said.

“It’s really about trying to figure out what having that willingness to help a person in crisis and working with them collaboratively to figure out the next steps.”

Lavoie has been working on the program with researcher Natalie Alvarez from Toronto Metropolitan University for the past six years.

The program itself was developed by Toronto-based immersive learning company Lumeto and the content was informed by community stakeholders, advocates, clinicians, nurses, forensic psychologists, and Indigenous cultural safety and anti-discrimination experts alongside police instructors from across Ontario.

Most importantly, the program had input from people with mental illness, who Lavoie said are more likely to be the victim of police violence.

“To be honest, sometimes it doesn’t go well. Often it doesn’t go well,” she said.

“So we have to acknowledge those shortcomings and those experiences and they have to be authentically incorporated in. Otherwise, this isn’t going to change.”

That process included considering how racialized people and members of the LGBTQ2 community who also have mental illness are even more disproportionately impacted, which is why one of the scenarios involves an Indigenous person who is hearing voices and another involves a young person who is transgender.

“Not knowing how to interact with community members, it’s not acceptable. We have to have a police service — if they’re responding, if they’re the ones that are going to mental health crisis situations, they have to know how to respond to all members of our community.”

So far, there are six virtual situations that officers can experience: three of those are 90-minute exercises that offer opportunities for discussion during training; and three are 10-minute assessments that evaluate officers on how they respond to an incident.

Hamilton’s police service has been the first in Ontario to get on board with the training program, but Lavoie said others have expressed interest and she hopes it will become more widespread.

“We want to standardize training across the province so that the kind of response I would receive if I was in crisis in Stratford, Ont., would be the same as in Toronto or would be the same here in Hamilton. And it’s not right now, it’s sort of all over the place.”

She also pointed out that there are cost benefits associated with using virtual reality training.

The program itself is free and they’ve already purchased the VR equipment for every municipal and First Nations police service in Ontario, so using the immersive technology would be cheaper than the cost of doing live in-person training.

Ultimately, the goal is to see fewer use-of-force incidents and fewer injuries inflicted by police in mental health crisis situations.

“So you could take a look at the behaviour of a group of officers the year before training, offer the training and then look at the year after, and say, do we see appreciable differences in police practice? That’s really the only way to see if training is effective or not.”

According to a media release, Hamilton police responded to 5,718 mental health crisis calls last year.

The data for use-of-force incidents for 2021 hasn’t yet been released but a report presented to the police services board last summer found that use-of-force incidents reached a decade high in 2020.

The service says it will incorporate the new VR training program into its current crisis intervention training, which sees about 75 new members taking part each year.

Comments