A researcher at the University of Saskatchewan believes canola meal pellets could be an eco-friendly alternative to both coal and natural gas for heat and energy.

Ajay Dalai has spent over five years researching the feasibility of turning leftover materials from crop production into biofuel.

He is now ready to produce the pellets on a large scale to test their consistency.

“Eventually, the world is going to phase out coal because of pollution,” said Dalia, Canada Research Chair in Bio-energy and Environmentally Friendly Chemical Processing at the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Engineering.

“The potential of using biomass to bioenergy is enormous and exciting.”

Dalai said the incentive to develop the technology came from the agriculture material available in Saskatchewan, particularly canola.

He said canola oil extraction typically leaves behind roughly 60 per cent of its original weight in meal.

Some is exported, and roughly 40 per cent is fed to livestock. Dalai sees the remainder being used as biofuel.

“The idea was, what we can do with this material to complement the energy mix that we are getting from fossil fuel.

“And that’s where the incentive came to develop a technology that can utilize the organic material matter we have in our backyard and complement the natural gas sector.”

Canola meal pellets

Dalai said the actual pellets are small, roughly half a centimetre long and three or four millimetres in diameter.

“What we do is we basically heat it to about 200 degrees C to drive water or drive volatiles.

“The carbon content goes up, the energy density goes up and then we use some amount of water, some of these ingredients to mix it and push it through a nozzle at a certain temperature to make these pellets.”

He said the pellets are strong, but not very heavy, and burn very well.

Get breaking National news

“It burns very, very cleanly, and the smell is a little bit better than if you’re burning coal, for example, or a heavy petroleum. So that also is beneficial.”

It is not a carbon-neutral process, but is environmentally friendly.

“It still involves some energy in terms of crop production, crop transportation, conversion into a pallet, transporting pellets,” Dalai explained.

“It involves some of that, just like any other energy source requires. We have to take that into account, but nonetheless, it will have a net positive emission.”

The synchrotron

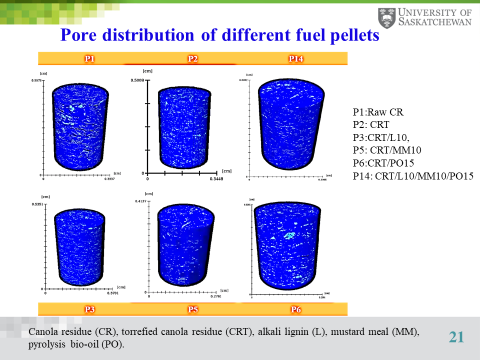

Once they had samples in place, Dalai and his colleagues turned to the Canadian Light Source to use computer techniques to examine their lab-produced pellets.

He said this allowed them to see what the structure looked like inside and determine the optimal amount of binders and lubricants to create a pellet that doesn’t absorb too much moisture or crumble when transported.

“Tomography allows us to assess the impact of different additives and different amounts of water on the mechanical strength of the pellet and the amount of energy produced when you burn it.”

The team used the synchrotron, which uses light to study the properties of materials at a molecular level, three times a year, for two to five days each time as they analyzed their raw material, with Canadian Light Source scientists helping to interpret and analyze the data.

“With the help of beamline scientists, it has been really teamwork, it’s not only people from our team.

“(They are) working very hard in the lab and creating the technology that we want and hopefully it’ll be materialized one day and benefit the society.”

Next steps

With newly arrived pellet-making equipment, Dalai’s team will work with industry partners to conduct an economic analysis.

“Are we ready to formulate and produce on a large scale for export? No, but our dream will come true one day,” he stated.

He said the climate is right to take the innovation from the lab to the field.

“When you look at the forest sector producing bio pellets, they make more than $300 million a year by exporting the bio pellets to Japan, the U.S.A. and U.K., and other countries.

“So now the question is, ‘What we can do to help the help the agricultural sector to convert some of the leftover organic matter to this product?’”

Dalia is not just looking at canola for producing pellets.

The findings from the canola meal pellets will be applied to other biomaterials such as canola hull, mustard meal and hull, and oat hull.

He is also hopeful the federal government will provide funding for his innovation.

Dalai said $100 billion was pledged annually by the signatories to the Paris Accord for renewable energy.

“So if Canada does its part, hopefully there will be a lot of money available to industry to take advantage of this canola meal,” he said.

“Government wins, farming community wins, and of course, the environment also benefits.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.