Feeling the pressures of a society plagued by climate change, soaring home prices, economic inequality and poverty, many young Canadians say they are feeling less than optimistic about the direction of our nation.

They don’t necessarily like the path that Canada’s on, and cite the baby boom generation as one of the root causes of disparity and division in Canadian society.

An Angus Reid Institute survey of young Canadian leaders found that almost half of respondents thought the answers to Canada’s woes rely not on fixing the past mistakes of previous generations, but, rather, starting anew with a complete restructuring of Canadian society.

The study asked Canadians of all ages to self-report on whether they consider themselves “leaders” in their communities. Respondents rated themselves on their ability to incite change in their communities through volunteering and political involvement.

These self-identified young leaders, all under the age of 41, said they were likely to prioritize the common good and generally believe that what’s good for society holds more importance than people’s individual rights and freedoms.

The young leaders also reported higher education levels and slightly more personal wealth than non-leaders, and were found to be far more diverse than their older counterparts in terms of race and gender.

A generational split

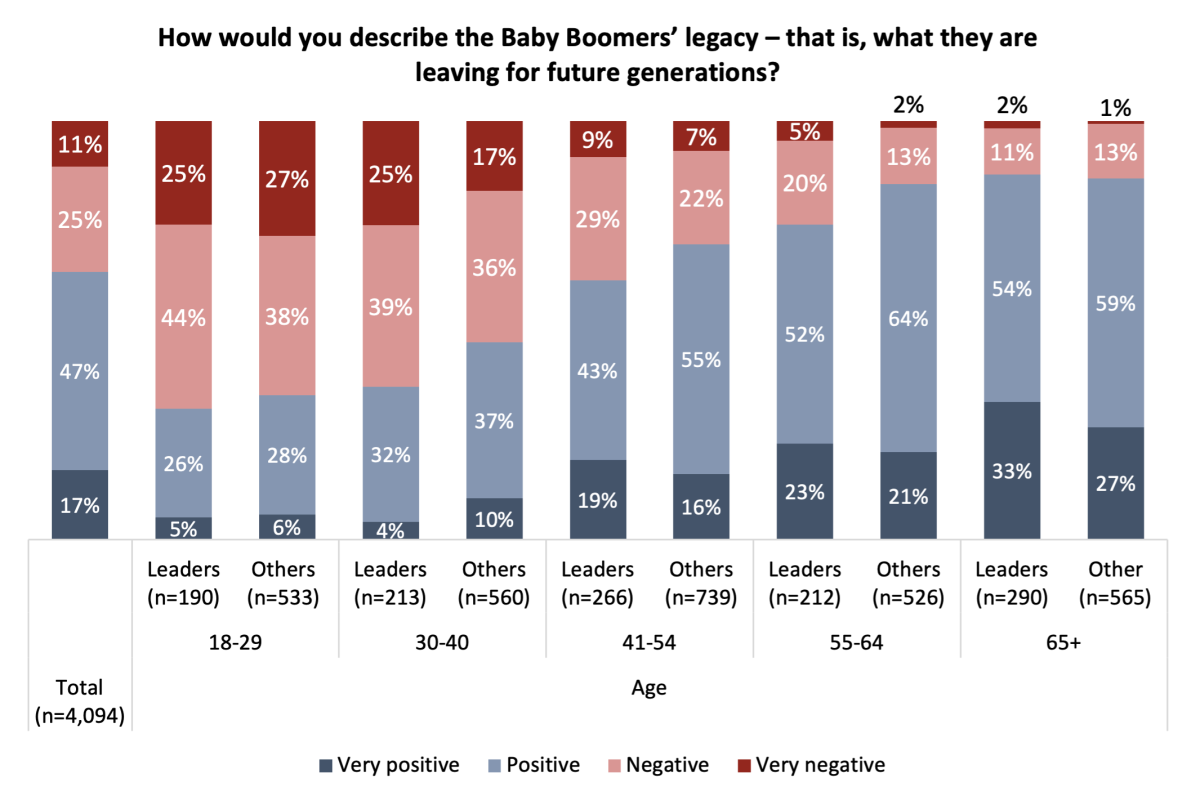

One thing most young leaders agree on is that the legacy of the baby boom generation may not be much of a legacy at all.

The majority of young leaders aged 40 and under said they view the boomers’ legacy as negative, while an overwhelming majority of leaders over the age of 55 view the legacy as positive.

“(Baby boomers) came of age at a very optimistic time — a time of economic growth, at a time of a feeling like things were getting better because they had some taste, at least from their parents, if not themselves, of how bad things had been,” Shachi Kurl, president of the Angus Reid Institute, told Global News.

Younger generations, however, are optimistic that the millennial generation will leave behind a more positive legacy than the boomers. On the flip side, older generations don’t have as much faith; half of those over the age of 40 think millennials will leave the world in worse shape.

The top issues

Get daily National news

The division between the two cohorts is real.

All survey respondents, regardless of generation, voted climate change as the top concern, and the majority said that Canada should emphasize environmental protection over economic growth.

Young leaders said they’re more concerned about economic inequality, housing prices, and Indigenous issues and reconciliation, while older leaders reported being more concerned about inflation and balancing the budget.

Kurl also points out that Canada is “at an inflection point” and is “very focused these days on what’s wrong.”

“I think we may be at a time where we’re too focused on the things that are going wrong and maybe not reflecting enough on the things that are going right.”

Who’s lucky?

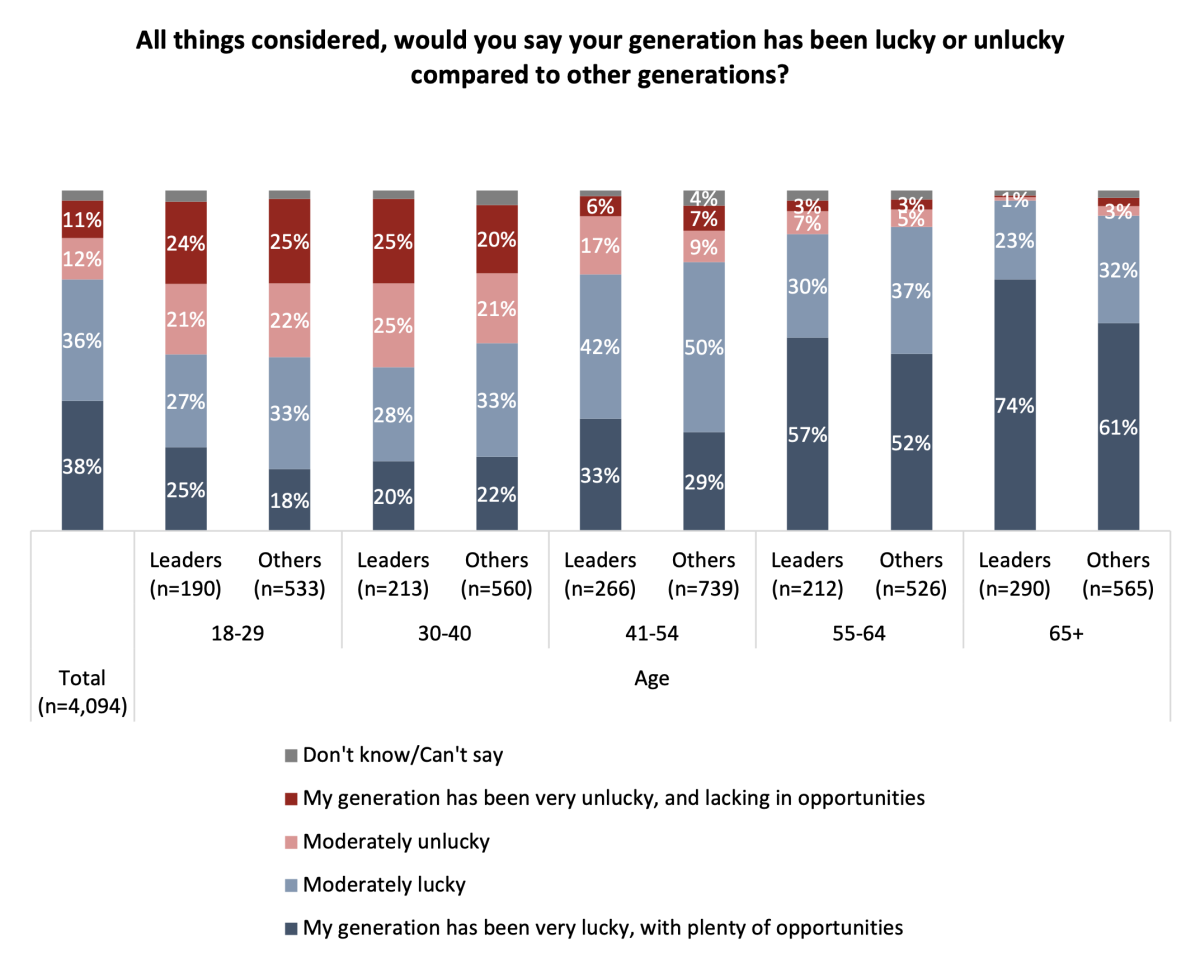

Younger Canadians were far more likely to say that their age group has been “unlucky,” with about 40 per cent of all leaders and their counterparts aged 40 and under saying that their generation has lacked opportunity. Older Canadians, especially those 55 and up, report being “very lucky” with plenty of opportunities.

Three-quarters of the leaders 40 and under agree that white people benefit from social opportunities not given to visible minorities, and almost 40 per cent reported attending a Black Lives Matter protest in 2020.

Older generations surveyed tend to feel most lucky in terms of overall quality of life, while the younger cohorts say they feel fortunate when it comes to social acceptance and freedom. Leaders aged 30 to 40 consider “opportunities for travel” to be their top area of luck, while older leaders rank property ownership as one of their lucky breaks.

A difference of views

It’s not simply a conversation about which generations have had it the easiest, or have had more opportunities in life.

The study also found that the way younger generations view Canada and the nation’s future is fundamentally different than that of their elders.

“You really do have a chasm, a really gaping chasm, between the way older (and younger) people look at what they’ve left behind in this country,” said Kurl.

“I think we are seeing a period of time in this country where younger generations are feeling incredible frustration over a number of things that are gripping society today…. They see nothing but problems, nothing but challenge, nothing but lack of equity and fairness. And they’re very angry about that.”

A majority of those older than 41 say they have a strong emotional attachment to Canada — they love the country and what it stands for — whereas only about half of those under 41 report having a strong allegiance to the country, and say they wouldn’t be opposed to pursuing opportunities in another country.

Technology, says Kurl, could be fuelling some feelings of detachment among the younger demographic.

“We’re consuming culture from any part of the world at any moment of the day … (and a) shared experience for Canadians is now just on-demand. You can get anything from anywhere. And I think it makes younger Canadians feel like perhaps they’re part of a more global society.”

Geographic location also plays a role in how Canadians view their country, with less than half of all Quebecers reporting a strong attachment to Canada, while seven in 10 Maritimers reported the same.

The path forward

So where does that leave us?

An analysis of the data provided shows not only a generational divide in the way younger and older Canadians view their country and what they consider to be the most important issues, both personally and as a country, but it also points to differences in how generations believe Canada should move forward to address these issues.

Half of the 18- to 29-year-old and two in five of the 30- to 40-year-old leaders say major structural change is needed and that Canada would benefit from starting fresh.

Those 55 and older, however, say that society would best benefit from continuing to build on the foundations already established by previous generations.

Kurl says it’s important to take into consideration the timing of the study, which was conducted earlier this year, and how the pressures of the pandemic might have skewed the survey’s responses.

“To what extent are we feeling a general depression or malaise that is perhaps furthered not only by very real problems, but also just by our mindsets in the middle of a pandemic?” she says. “Will we feel that lifted or will we feel a sense of optimism? We’ll have to go back and check that out.”

—

The Angus Reid Institute conducted an online survey from July 26 – Aug. 2, 2021, among a representative randomized sample of 4,094 Canadian adults who are members of Angus Reid Forum. For comparison purposes only, a probability sample of this size would carry a margin of error of +/- 1.5 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

Discrepancies in or between totals are due to rounding. The survey was self-commissioned and paid for by ARI. This included an augmented survey sample of those who qualified as “leaders” in

several pre-screening surveys.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.