The majority of Canadians live in parts of the country where air pollution exceeds new guidelines set by the World Health Organization, and this could damage their health, researchers say.

According to researchers at CANUE – the Canadian Urban Environmental Health Research Consortium – around 86 per cent of Canadians live in areas where airborne fine particulate matter levels exceed the WHO guidelines that were issued in late September.

Around 56 per cent of people live in areas where the levels of nitrogen dioxide exceed the new guidelines, said Jeff Brook, an assistant professor in public health and chemical engineering and applied chemistry at the University of Toronto who works with CANUE.

The WHO’s new guidelines recommend an annual average concentration of PM2.5 of five micrograms per cubic meter of air. PM2.5 refers to airborne particles so tiny that they can penetrate the lungs when you breathe and enter the bloodstream.

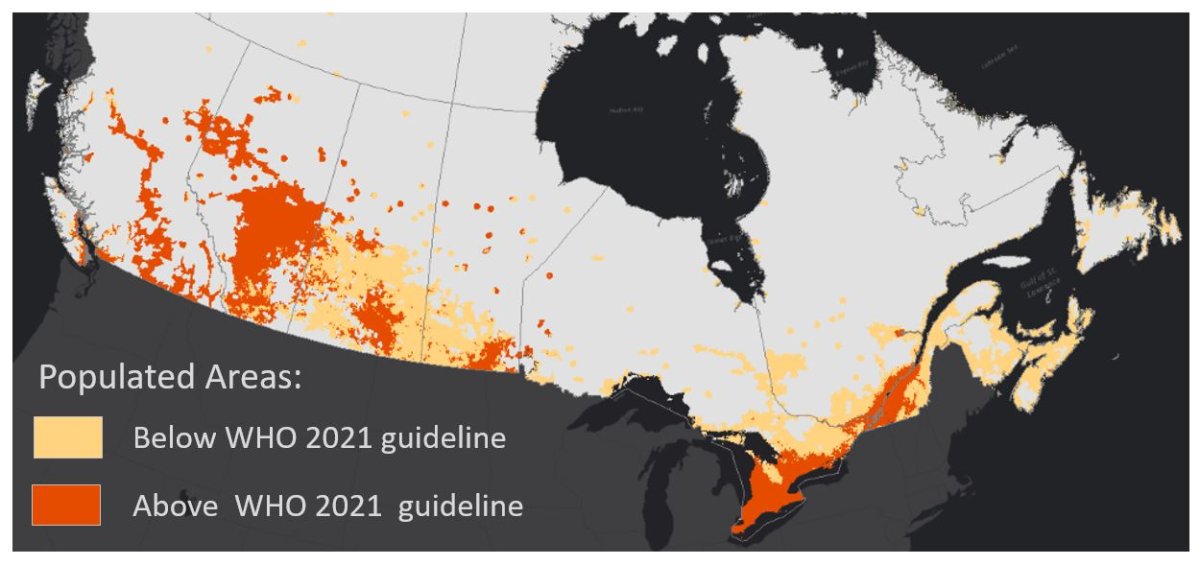

While most of Canada was well under the old WHO guideline on fine particulate matter, much of urban Canada exceeds this new benchmark, as do parts of Western Canada with regular exposure to wildfire smoke, CANUE’s research shows.

“We should care because we can do something about it,” said Brook, who is also a former air quality scientist for Environment Canada. “It is contributing to the costs of health care. It is affecting the quality of people’s lives.”

In a statement, Environment Canada said that it welcomes the new air quality guidelines from the WHO. “These guidelines will help to inform the next steps Canada takes to address air pollution and protect the air we breathe,” the agency wrote.

MAP: Areas exceeding WHO air quality guidelines on fine particulate matter

Health Canada estimates that air pollution contributes to 15,300 deaths per year in Canada, with many more people losing days suffering from asthma and acute respiratory symptoms as a result of pollution. This is a little more than the number of Canadians who die annually in accidents like car crashes, according to Statistics Canada.

Other studies come to similar conclusions as the research from CANUE. A recent report from the B.C. Lung Association found that many B.C. municipalities, including Victoria, much of the Lower Mainland and especially communities in the Interior like Grand Forks, Castlegar and Nelson, exceeded these levels.

Get weekly health news

In Ontario, according to a 2018 government report on annual trends in air quality – the most recent year available – air pollution across Toronto also exceeded these recommended levels, with downtown Toronto recording more than double the new WHO guideline.

“Our most polluted part of Canada would be the Windsor, Sarnia towards Montreal, Quebec City (corridor),” Brook said. “But increasingly, our most serious air pollution problems in Canada are where there’s forest fires.”

Canada’s air quality is consistently ranked among the cleanest in the world, Environment Canada wrote. But the agency is currently reviewing the national standards for fine particulate matter “to ensure they reflect the latest health and science information.”

Air pollution and health

The WHO’s new guidelines on PM2.5 and NO2 are significantly lower than the old ones. They are not enforceable in any way – but are merely a guide to help countries move toward cleaner air, said Michael Brauer, a professor in the school of population and public health at UBC who worked on the guidelines.

“The idea behind these guidelines is that they’re entirely health-based,” he said. “This is a five-year process and really pretty intense and detailed evaluation of the available evidence of the health impacts of air pollution.”

While Canada has much cleaner air than many other parts of the world, like India where annual average PM2.5 levels are 83 micrograms per cubic meter, that doesn’t mean Canadians don’t experience health impacts as a result of air pollution, Brauer said.

“Especially for particulate matter, for PM2.5, we see more people dying. So it’s really as simple as that. It’s the ultimate health impact,” Brauer said.

While air pollution might not be written on a death certificate, Brauer said, it’s been linked to lung disease, heart disease, asthma, and heart attacks and emerging evidence also suggests a link to type 2 diabetes and neurodegenerative conditions, according to the WHO.

Outdoor air pollution has long been linked to reduced lung function in otherwise healthy people, said Dr. Erika Penz, a respirologist and associate professor at the University of Saskatchewan. But what really concerns her as a respirologist is the impact on people with existing lung conditions, like asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

“We’ve actually seen even higher death rates in our patients with lung disease when faced with higher levels of air pollution,” she said.

During wildfire season in Saskatchewan, she said, “many, many, many of my patients call my office because they’re having troubles with breathing. Some of them show up in the emergency department, unfortunately, because they just can’t get control of their symptoms.

“And many of my patients, fortunately, just know that they’re not leaving the house for the period of time that the air quality is bad. And so they keep their windows closed and they don’t go out in order to protect themselves.”

“I think many people could appreciate if you’re in very good health, you’re exposed to air pollution, you may develop a cough or slight difficulty breathing for a day or two, for example, in a wildfire smoke event,” Brauer said. “But over the course of a lifetime, these repeated insults really lead to quite severe impacts in combination with other things.”

Canada’s wildfire seasons are likely to get worse, B.C. Centre for Disease Control researcher Sarah Henderson told Global News this summer. “All of the research suggests that we will see increasingly severe and prolonged wildfire seasons, and that means increasingly severe long smoke exposures,” she said.

Reducing air pollution should be a priority for governments, Penz said, and she predicts that Canada will see increasing rates of health issues linked to pollution in the years to come.

“From a just a patient level, it makes sense to do that to improve the overall health of our populations, to prevent the issues that we see in our hospitals,” she said. “These patients come in and require care and some of them don’t have good outcomes, they end up even dying from these diseases.”

While it’s hard to stop pollution from wildfires, Canada can also work on reducing pollution from traffic and other urban sources, Brook said. “Every improvement and exposure reduction is a benefit,” he said.

This might be through slowly introducing regulations on cars, limiting truck traffic in cities, or limiting the use of indoor fireplaces in urban areas, Brauer said.

“If we lower air pollution, everybody wins,” he said. “Just from a health perspective, it’s one of the most efficient ways we can actually improve the health of the population.”

- ‘More than just a fad’: Federal petition seeks tax relief for those with celiac disease

- Canada approves Moderna’s RSV vaccine, first of its kind for older adults

- ‘Huge surge’ in U.S. abortion pill demand after Trump’s election win

- New Brunswick to allow medicare to pay for surgical abortions outside hospitals

Comments