Canada has nearly 1,000 historic sites across the country that have been officially recognized by the federal government, but only nine of them speak to Black history.

In a statement emailed to Global News, Parks Canada said the Historic Sites and Monuments Board (HSMBC) recognized the national historic significance of the Underground Railroad in 1925.

“This designation, among the earliest by the HSMBC, was the first that identified Black History as an integral part of Canada’s past,” the statement read.

“Since that time, nine national historic sites, 12 national historic events and 17 historic persons that speak to Black History in Canada have been recognized under the National Program of Historical Commemoration.”

Formally designated churches, settlements, community organizations and individuals are commemorated with an official plaque outlining their significance to Canadian history.

Officially designating these sites is important because “it’s a way of honouring and remembering Black history,” said Afua Cooper, a professor at Dalhousie University’s department of sociology and social anthropology.

“For so long, Black history in Canada has been erased, marginalized, and in the case of Africville, bulldozed and buried,” she said. “So it’s really important because these plaques tell us that Black people struggle against racism.”

She said it’s a “tremendous project” that has been undertaken by Parks Canada.

“When the federal government does something like this, it has punch, it has significance,” she said. “It has meaning and people take it seriously.”

Here’s a look at some of the federally recognized historic sites that commemorate Black history in Canada.

Africville

Africville, located in Halifax, Nova Scotia, was a small settlement of African Canadians in the 1830s and 1840s.

The community continued to grow in Nova Scotia, despite being denied resources and amenities from the city until 1960s when it was dismantled and cleared during the “urban renewal movement.”

The nearly 400 residents of Africville were forced to relocate as their community was completely destroyed.

Most were not compensated for the loss of their homes and community.

In 2010, the mayor of Halifax formally apologized.

“You lost your homes, your church, all the places in which you gathered with your family and friends to share and mark the milestones of your lives,” then-mayor Peter Kelly said.

“For all of that, we apologize.”

However, many survivors and descendants are still calling on the government for compensation.

Get breaking National news

Parks Canada said before it was relocated, Africville was “representative of Black settlement in Nova Scotia in its social organization and in its geographical and metaphorical position on the periphery of white society.”

The agency said the clearance of Africville “in the name of urban renewal became an enduring symbol to Black Canadians of the need for vigilance in defence of their institutions.”

Africville was officially designated as a national historic site in 1997.

Griffin House

Perched atop a hill in what is now Hamilton, Ont., is a small home known as the Griffin House.

The house was built around 1827, and became the home of Enerals Griffin, a Black immigrant from Virginia in 1834.

According to Parks Canada, the house is significant because it is “associated with Black settlement in British North America during the first half of the 19th century.”

The house, the agency said, “conveys the complexity of the Black experience” because it is more elaborate than was common among Black refugees and because of its location in a Euro-Canadian community in south-central Ontario “rather than a planned refugee settlement in south-western Ontario.”

Salem Chapel

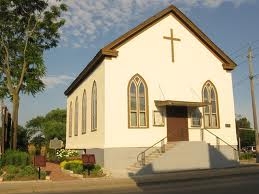

A number of churches have been designated as national historic sites in Canada, including the Oro African Methodist Church, the Sandwich First Baptist Church, the Nazrey African Episcopal Church and the R. Nathaniel Dett British Methodist Episcopal Church.

However, perhaps most well known is Salem Chapel, located in St. Catharines Ont.

The chapel was built in 1855, and became an important location for the civil rights and abolitionist movements in Canada.

Harriet Tubman, one of history’s most famous Underground Railroad “conductors” was a member of the congregation.

Tubman was officially designated a national historic person in 2005 for her work in leading hundreds of slaves fleeing from the southern states to the north.

Tubman is estimated to have helped 300 people fleeing slavery cross into Canada.

According to Parks Canada, “many of those aided to freedom became church members and put down roots in the local community.”

“The heritage value of this church resides in its exceptional associations with the anti-slavery movement and the early (Underground Railroad) Black community to which it bears witness as illustrated by the church with its auditory-hall form, typical of early African Canadian churches,” the website reads.

Buxton National Historic Site and Museum

The Buxton National Historic site sits on the original site of the Elgin Settelment in North Buxton, Ont.

The site acted as a transportation line for the Underground Railroad, which aided Black people fleeing slavery in the United States.

The settlement was founded by Rev. William King, a former slave owner who became an abolitionist, and 15 former American slaves in 1849.

According to Parks Canada, the cultural landscape “continues as a living memorial to its founders and to the courage of every Underground Railroad refugee who took their life in their hands and chose Canada as their home,” the website reads.

Today, a museum complete with a library and research centre sit on the site.

Amherstberg First Baptist Church

The Amherstberg First Baptist Church is located in Amherstberg, in southwestern Ontario.

The church was constructed in 1848, and served as a safe place for Black Americans fleeing slavery to stay once they crossed into Canada.

According to Parks Canada, the building was important “in the everyday lives of congregants and to the development of a distinctive Black Baptist church tradition in Ontario.”

The agency said the church played a “crucial role” in the development of Black communities and identity in the province by “founding an organization within which people of African descent could pursue their ambitions, develop their talents, and assume positions of leadership at a time when they were denied these opportunities elsewhere.”

New designations

To date, the HSMBC has made over 2,150 designations across Canada.

However, only approximately 1.7 per cent of the historic sites, people and events officially recognized are dedicated to Black history in Canada.

Parks Canada said of the nearly 1,000 national historic sites in Canada, 151 are administered by the agency.

Cooper said she is not surprised that so few designations have been made, because so much of Black History in Canada has been erased.

However, in July of 2020, four new designations were announced by the federal government to “help to shed light on the collective and personal experiences of Black Canadians and their struggles for freedom, equality and justice.”

The new designations included the enslavement of African People in Canada, Black Loyalist Richard Pierpoint, Heavyweight Boxer Larry Gains and the West Indian Domestic Scheme.

Cooper said she is encouraged by the move, but said there is more work to be done to have other important Black figures and historic sites formally recognized.

“We have to do the work,” she said. “We just have to say ‘look, we’re going to do this’ and go through the process.”

Cooper encouraged anyone who knows of a person, place or event of significance to submit an application to Parks Canada and the HSMBC.

She said formally designating important people, places and events is a “fantastic way” to teach about Black history.

“Oftentimes when you look in the textbooks on Canadian history, there’s hardly anything about the Black community and the achievements and the contribution plaques are fantastic to tell that story,” she said.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.