Six months have passed since Saskatchewan reported its first case of COVID-19.

On March 12, the province reported that a patient in their late 60s who had recently travelled to Egypt had tested positive for the novel coronavirus.

“We’ve been through six months of the pandemic,” Dr. Saqib Shahab, the province’s chief medical health officer, said on Sept. 4.

“Our case numbers are so low and this is a time to pause and congratulate ourselves and move confidently forward to back-to-school, back to work as we enter fall.”

Dr. Cory Neudorf, a professor in epidemiology at the University of Saskatchewan, said the response to the coronavirus has been “one big learning experience for everyone.”

“As we look at how Canada has responded and how well Saskatchewan has responded, it’s been very much tied up in that overall global response and an understanding that we’ve learned from other places where the virus hit first how serious this can be if we don’t take it seriously,” Neudorf told Global News in an interview.

“Looking at the unprecedented response that we’ve seen in terms of shut down of many aspects of normal life and society and then the adaptations that we’ve come to put into play tentatively, that’s been exactly what was needed.”

How has Saskatchewan fared during the first six months of the pandemic?

- ‘A foreign policy based on short memory’: Carney continues push to diversify from the U.S.

- Mother of B.C. mass shooting survivor shares update, says breathing tube removed

- Carney says former prince Andrew should be removed from line to throne

- Canada and Japan sign partnership deal on defence, energy, trade

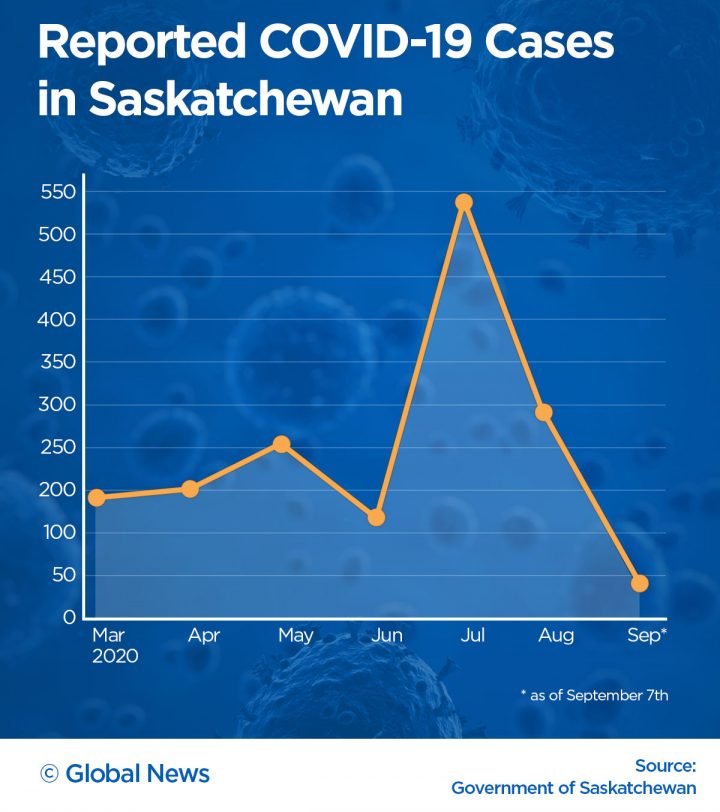

During the first four months, the number of monthly confirmed cases remained stable — from a low of 139 in June to a high of 257 in May.

May’s numbers were driven by the province’s first spike when 116 new cases were reported during the first week. The majority of those were traced to an outbreak in the La Loche area.

That changed in July.

The province reported 534 cases that month, 349 of which were reported in the last 10 days of July, most traced to outbreaks at several Hutterite colonies and neighbouring communities.

July 22 saw the province’s largest single-day rise since the start of the pandemic when 60 new cases were reported.

Saskatchewan also surpassed 1,000 confirmed cases that day.

By July 29, there were 322 known active coronavirus cases — the highest daily number reached over the past six months.

Neudorf said along with public safety measure compliance, Saskatchewan’s low population density played a factor in outbreak numbers.

“We have examples of where (spikes) happen, especially in low-income areas or with some of our reserve communities, communal living. Those areas, there needs to be a lot more vigilance and those are areas where we can see more spikes in cases,” he explained.

Get weekly health news

“But for the most part, what we’re seeing is people, where they can, taking those restrictions more seriously and the key is going to be if we can find early signs of a resurgence, getting people to, again, be more vigilant as a group.”

As of the morning on Sept. 12, 1,688 total cases had been reported, along with 24 coronavirus-related deaths.

Testing numbers lag compared to Canada

Saskatchewan has performed over 150,000 tests to-date for the novel coronavirus.

The per capita testing rate in the province as of Sept. 5 was 107,241 people tested per one million population. The national rate is 153,795 people tested per one million population.

Neudorf said Saskatchewan was initially near the top of per capita testing in the country, but that has slowly dropped off over time.

“The capacity has been there. It’s been more an issue of people availing themselves of that and in some respects, that might be that we’ve had fewer people who are symptomatic and therefore not as much testing demand,” he said.

“It’s been largely an issue of public demand differences rather than testing availability in this province, as far as I can see.”

Before July 17, there were only three days when over 1,000 daily tests were performed: March 22 (1,348), April 9 (1,051) and June 27 (1,045).

Since then, the number of daily tests has routinely been over 1,000, with over 2,000 tests performed on five days: Aug. 2 (2,104), Aug. 7 (2,129), Aug. 15 (2,016), Sept. 5 (2,123) and Sept. 6 (2,081).

Health officials said testing numbers started to rise in mid-July when universal testing started.

This allowed anyone who wants a test to get one regardless if they have COVID-19 symptoms.

Saskatchewan further expanded testing in September with drive-through sites opening in Regina and Saskatoon.

Transmission of the coronavirus changes over time

The majority of cases first reported in Saskatchewan were travel-related, which eventually changing to community contacts — including mass gatherings.

Neudorf said this is typical in the common evolution of a virus.

“The first cases that you’re going to see are going to be related to travel unless the virus emerges first in your part of the world.”

He said the degree it spreads in the community depends on a couple of factors.

“First of all, how good is your surveillance in picking up new travellers that might have it or containing the spread from those initial cases? And secondly, to what extent is the virus spread when it’s pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic in those individuals?”

“Certainly, evidence points to now that there’s a larger role for spread before people exhibit symptoms or in some cases, even if they remain asymptomatic but have the virus, that they can spread it,” Neudorf explained.

Second wave and seasonal influenza

There are concerns about a second wave of COVID-19 as schools re-open, more people return to the workplace and more indoor gatherings take place in the community.

Neudorf said the extent of the second wave will depend on the public continuing to maintain proper physical distancing, limiting the size of gatherings, observing proper hand hygiene and wearing masks.

“To the extent that we keep vigilant on those, then the number of new cases we’ll see or the size of that wave will be drastically reduced,” he said.

“But, if we combine re-opening with loosening all of those other factors that we’re in control of personally, then the wave will very quickly rise and we’ll have a massive second wave.”

The other factor is the seasonal flu.

Neudorf said the coronavirus spreads as easily as the flu but is far more serious.

“The number of deaths, or the percentage of deaths, that it causes compared to seasonal flu is much, much higher. So it has that unfortunate confluence of factors where it’s both easily spread but more dangerous than seasonal flu,” he said.

“From a virus perspective, it seems to be pretty well designed to cause havoc and therefore, we need to treat it differently.”

Neudorf said that studies indicate less than one per cent of the population has contracted COVID.

“So the vast, vast majority of us have not seen this yet and yet we’ve seen the disruption it’s caused already. So that means that we still have time,” he said.

“But it also means that we’re still in for a rough ride if we don’t adhere to those personal measures until a vaccine becomes available.”

When will a vaccine be ready?

There are currently 34 vaccine candidates in various clinical trial phases, including one in Canada, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Some have reached the critical Phase 3.

In this stage, the vaccine is given to an even larger group of people (ranging from 1,000 to 50,000) to monitor its effectiveness, side effects and to compare it to commonly used treatments, Health Canada’s website explains. Sometimes a placebo is used.

Neudorf said the availability of a vaccine is still months away.

“The earliest estimates we’re continuing to hear would be toward the beginning to middle of next year,” he said.

“So middle of our winter or early spring for any kind of volume of an effective vaccine to be available here.”

Until then, Neudorf has this advice.

“We’re all in this together and that the measures that we take certainly protect us and our family and our extended family and they protect others as well.

“(Don’t) succumb to politicizing factors like mask-wearing or washing of hands or keeping our distance. Just recognize that this is something we have to do for a time because it works and let’s just try to pull together.”

— With a file from Katie Dangerfield

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.