As officials across Canada struggle with how to reconcile the problematic legacies of the country’s historical figures, a national cemetery in Ottawa could show the path to presenting Canadian history in context — warts and all.

The Beechwood Cemetery in the nation’s capital is the final resting place for some of Canada’s most enduring figures.

Among the dead here are former NDP leader Tommy Douglas, former Ottawa Mayor Marion Dewar and Sir Robert Borden, prime minister of Canada during the First World War.

But as debate rages over Montreal’s toppled statue of another notable prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, and other Canadians with similarly problematic legacies, Beechwood has been taking the good with the bad through a plaque program designed to give context to its inhabitants.

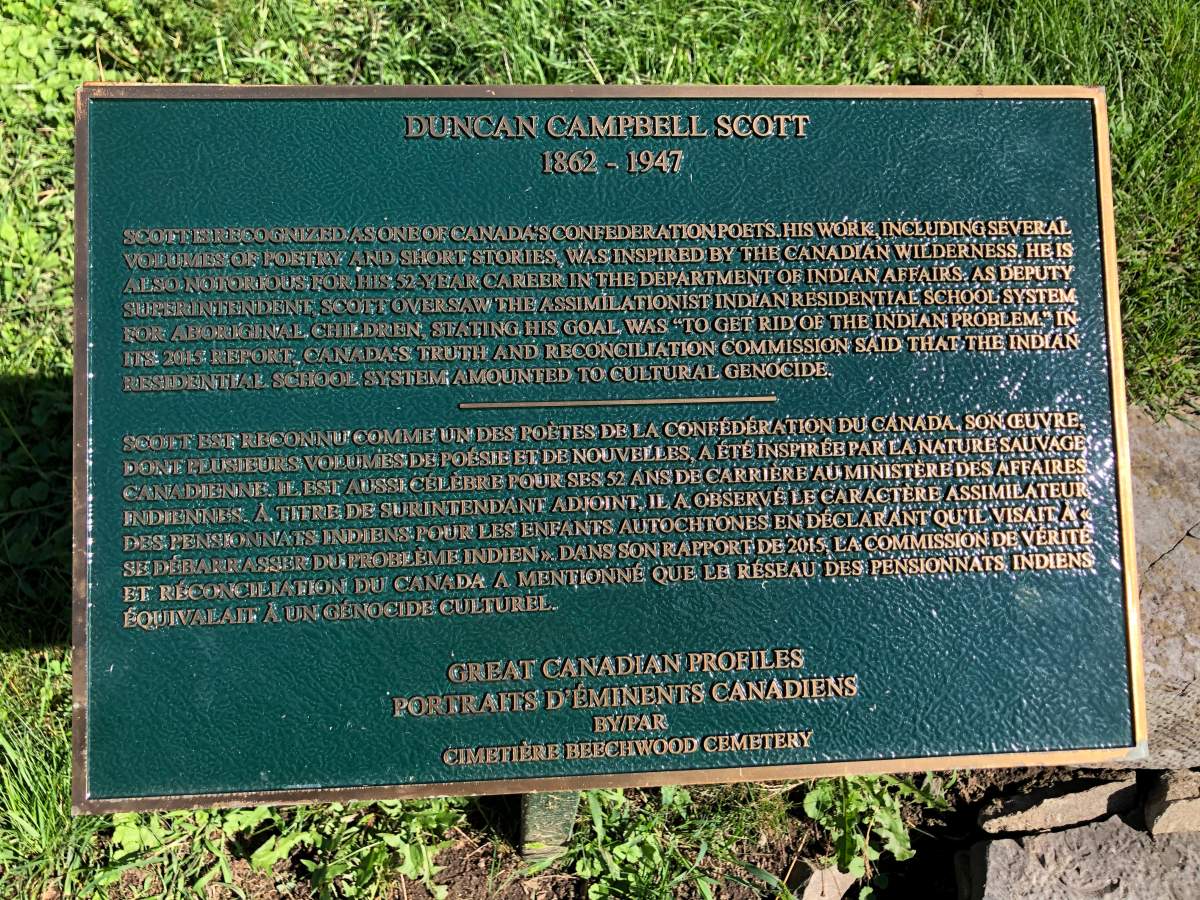

Take, for instance, the plaque honouring Duncan Campbell Scott, a renowned Canadian poet.

Scott’s plaque originally extolled his virtues with the written word but made no mention of his time as Canada’s first minister of Indian affairs, during which time he oversaw and implemented the residential school program.

The 2015 report from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission found the program, which saw Indigenous children taken from their families, re-educated through Christian indoctrination and forced to live in horrendous conditions, amounted to “cultural genocide” that resulted in the deaths of thousands of children.

Hailing Scott as a hero with no mention of his role in the residential school program irked Cindy Blackstock when she walked through Beechwood a few years ago.

She started mounting a case, in collaboration with members of Scott’s own faith group, for the cemetery to update his plaque to reflect the whole story of the late minister’s contributions to Canada.

She found the cemetery, surprisingly, needed little convincing, and the plaque was removed and subsequently updated in 2015 to reflect both his contributions as a poet and his role in cultural genocide.

Nicholas McCarthy, director of marketing, communications and community outreach at Beechwood Cemetery, says this is a model for reconciling the good with the bad when it comes to Canada’s historical figures.

“We’re talking about reconciliation. That’s what we need to focus on, the openness to understand that, yes, this person was a phenomenal poet. But, yes, he instituted a system that killed children all across Canada,” McCarthy tells Global News.

Beechwood’s reconciliation plaque project also serves to highlight Canadians whose contributions were not recognized in their own time.

Peter Henderson Bryce wrote a report in the 1920s about the health conditions in residential schools titled “A National Crime.”

Get breaking National news

His report, which laid bare the crimes committed against the Indigenous students of these schools, was roundly ignored by the federal government and he was subsequently pushed out of the public service.

A new plaque tells visitors to his grave about his attempts to save the lives of Indigenous children in these schools.

“He sounded the first alarm,” McCarthy says.

Blackstock, who works as the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, has been lobbying to set up an official walking tour along Sparks Street in Ottawa where visitors can learn the history of the buildings where the likes of Bryce and Scott used to work.

She would like to see a guided tour with plaques installed at the buildings and QR codes that could show what the sites looked like 100 years ago and provide context about the anti-Indigenous policies that were crafted there.

“I think people have a different reaction to actually looking at a building and imagining for themselves someone walking in there with a report that could save thousands of children’s lives, had the government of Canada only listened,” she says.

Though she says she has the City of Ottawa on board with the tour, Blackstock says she has yet to get support from the National Capital Commission to install plaques.

Steven Guilbeault, minister of Canadian Heritage, tells Global News that debates over Sir John A. Macdonald’s statue show the government has to do a “better job” at telling Canada’s history and be more inclusive of the roles of Indigenous people and immigrants in shaping the country.

Guilbeault says the decision of whether to preserve or pull down statues of historical figures shouldn’t be decided by a group of protesters.

“We have to come to the decisions together on how we do it and do this in an orderly manner. Taking down statues like that, it’s clearly not not the way to go,” he says.

Blackstock says statues of leaders who instituted racist policies should not stand in public spaces where Indigenous, Métis and Inuit people are forced to walk past every day.

Instead, they should be placed in areas where it’s appropriate to learn about the figure’s full historical context.

“What they need to do is trust Canadians with the truth,” Blackstock says.

“They need to say that, yes, MacDonald was involved in bringing in the various elements of the colonies to create Canada. But, yes, he also was a racist, even for his time among his contemporaries.”

McCarthy says that’s ultimately the role of Beechwood’s reconciliation plaque program, to provide the “missing context” that merges Indigenous history with the stories Canadians learned growing up.

“It’s not black and white. It’s grey. And that’s where people really have to understand that history should be sort of understood in the grey area,” he says.

— With reporting from Global News’ Mike Le Couteur

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.