As of July 18, it is mandatory to wear masks in indoor public spaces in Québec following similar edicts across the country.

While inspired by growing evidence that masks can reduce the spread of COVID-19, this seems deeply ironic in a province so opposed to face coverings that Québec passed legislation that forbade people from receiving certain government services if their face was covered.

READ MORE: People who wear face masks do not stop washing their hands, study finds

The Toronto Transit Commission made face coverings mandatory at the beginning of July. And yet, just three years ago, TTC workers were forbidden from wearing masks to protect themselves against air pollution in the subway system. The TTC also instructed its workers not to wear masks during the 2003 SARS epidemic in Toronto.

Clearly, our discomfort about wearing masks in the midst of a pandemic has deep roots.

Bad smells and bird beaks

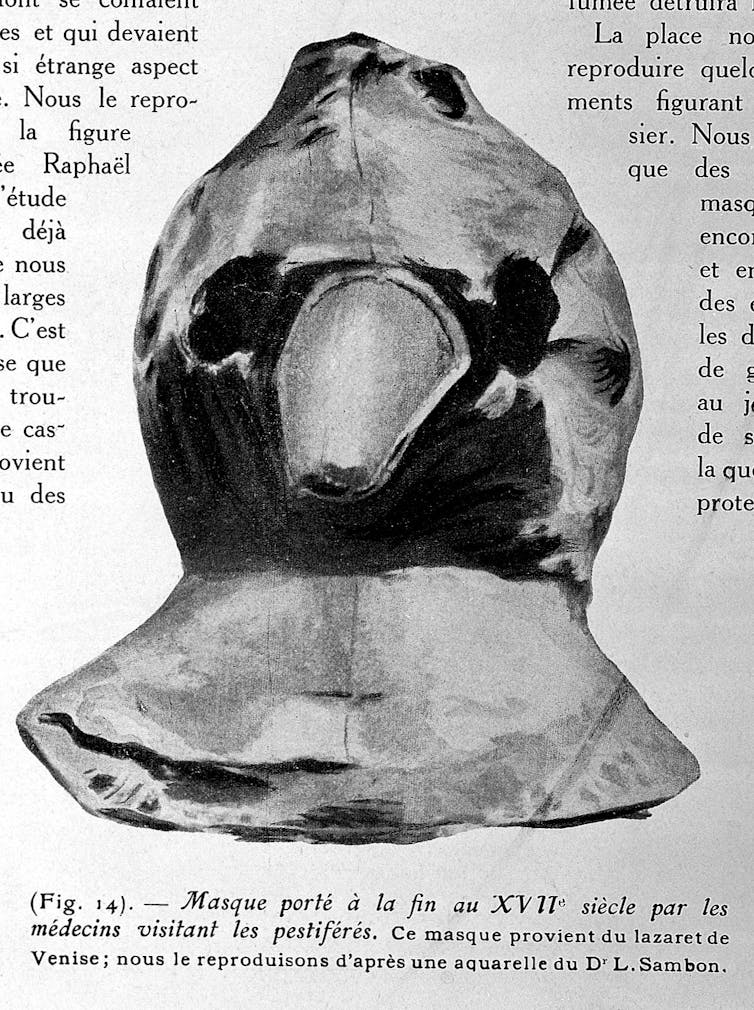

Medical mask-wearing has a long history. In the past few months, pictures of the beaked masks that doctors wore during the 17th-century plague epidemic have been circulating online. At the time, disease was believed to spread through miasmas — bad smells that wafted through the air. The beak was stuffed with herbs, spices and dried flowers to ward off the odors believed to spread the plague.

In North America, before the 1918 influenza epidemic, surgeons wore masks, as did nurses and doctors who were treating contagious patients in a hospital setting. But during the flu epidemic, cities around the world passed mandatory masking orders. Historian Nancy Tomes argues that mask-wearing was embraced by the American public as “an emblem of public spiritedness and discipline.”

Women accustomed to knitting socks and rolling bandages for soldiers quickly took to mask-making as a patriotic duty. That said, the enthusiasm for mask-wearing waned quickly, as Alfred W. Crosby showed in America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918.

Canadian reluctance and Japanese willingness

Get breaking National news

In her study of the 1918 flu in Canada, historian Janice Dickin McGinnis argued that masks were “widely unpopular” and that even in places with mandatory masking orders in place, people often failed to wear them or just pulled them on when police appeared.

Public health officers were dubious about the value of masks. In Alberta, for example, the flu first appeared at the beginning of October 1918. By the end of the month, the province ordered everyone to wear a mask outside of their homes, to be removed only in the case of eating. In just four weeks, the order was rescinded.

The Medical Officer of Health for Edmonton reported that practically no one wore a mask thereafter, except in hospitals. In his view, the rapid spread of the disease after the mask order was put into effect made the order an object of “ridicule.”

- Queen’s University students stranded in Doha after Iran attack shuts down airspace

- Iran begins search for new leader; U.S. military says 3 service members killed

- Attack on Iran triggers global flight disruptions, impacts Canadian travellers

- Carney calls for protection of civilians as U.S., Israel strike Iran

In Japan, by contrast, the public embraced mask-wearing during the Spanish flu. According to sociologist Mitsutoshi Horii, mask-wearing symbolized “modernity.” In the post-war era, Japanese people continued to wear masks to prevent the flu, only stopping in the 1970s when flu vaccines became widely available. In the 1980s and 1990s, mask-wearing increased to prevent allergies, as allergy to cedar pollen became a growing problem. In the late 1980s, the effectiveness of flu vaccinations declined and wearing a mask to avoid influenza resumed.

Mask-wearing skyrocketed in the early years of the 21st century with the outbreak of SARS and avian influenza. The Japanese government recommended that all sick people wear masks to protect others, while they suggested that healthy people could wear them as a preventative measure. Horii argues that mask-wearing was a “neoliberal answer to the question of public health policy” in that it encouraged people to take individual responsibility for their own health.

When H1N1 hit Japan in 2009, it first struck tourists who had returned from Canada. The sick were blamed for failing to wear masks while abroad. In a country that takes etiquette very seriously, wearing masks in Japan has become a form of politeness.

A century of Chinese mask-wearing

Similarly, in China, mask-wearing has a long history. A pneumonic plague epidemic in China in 1910-11 sparked widespread mask-wearing there. After the Communists came to power in 1949, there was intense fear of germ warfare, leading many to wear masks. In the 21st century, the SARS epidemic intensified mask-wearing, as did the smog that blanketed many Chinese cities. The Chinese government urged its citizens to protect themselves against pollution by wearing masks.

During the COVID-19 epidemic, some of the first people in Canada to wear masks were people with ties to Asia, who were already accustomed to the practice of masking.

One of the first cases of COVID-19 in Canada was that of a student at Western University who had visited her parents in Wuhan over the Christmas break. On the flight back to Canada, she wore a mask. She self-isolated upon her arrival in Canada and when she became sick, she showed up at the hospital wearing a mask. She did not infect anyone else.

READ MORE: Which mask should I buy? From cotton to silk, finding the right fabrics

Crafting masks

Long before Etsy crafters and Old Navy began producing fashionable masks for the North American market, colourful masks were available in India, Taiwan, Thailand and other Asian countries. During the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong, the New York Times reported that consumers could purchase masks with Hello Kitty and other cartoon characters, as well American flag masks meant to show the wearer’s support for democracy.

Ironically, given that the masks are intended to protect others, mask-wearing has made Asians in Canada a target of racist attacks. In the early days of COVID-19, Western media outlets featured Asians wearing masks as a harbinger of the epidemic. Asians wearing masks have been verbally and physically attacked.

Contentious choices

Controversies over masks continue. On July 15, a man died after a confrontation with the Ontario Provincial Police after he reportedly assaulted staff at a grocery store who insisted he wear a mask. Some Canadians complain that masks are uncomfortable, unnecessary, harmful to their own health or ineffective.

Masks can be a visual representation of the threat of COVID-19 and make people feel more fearful; an “optimism bias” can make people reluctant to wear masks because they think that the novel coronavirus will not affect them. There are also real concerns that masks impede communication for frail elders and the hearing impaired.

But support for mask-wearing appears to be growing. In the face of a serious health threat, Canadians are wisely following the lead of Asian countries.Catherine Carstairs, Professor, Department of History, University of Guelph

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.