Oops.

Hungarian scientists say they accidentally played God with two endangered species of fish, breeding a Russian sturgeon with an American paddlefish to create something the world has never seen before: the sturddlefish.

The sturddlefish’s parents are two extremely old, so-called “fossil fish” species that developed in different parts of the world and have never been bred before. However, they do have distant genetic connections as members of the order of Acipenseriformes, a broad category of ray-like fish that includes paddlefish and sturgeons.

The American paddlefish has a long, sensitive snout and typically eats plankton and microscopic plants, while the spiny-backed Russian sturgeon is known for devouring small fish and crustaceans found on the bottoms of rivers and lakes. The Russian sturgeon is also famous for its eggs, which make for delicious caviar and, apparently, viable Frankenfish.

Hungarian researchers accidentally created the first hybrid during a failed attempt at getting the endangered sturgeon to reproduce asexually. The process, called gynogenesis, involves exposing an egg to sperm, although the sperm isn’t supposed to fertilize the egg with its DNA.

Something went awry with the process, and the paddlefish sperm added its DNA to several sturgeon eggs, creating embryos that spawned hundreds of brand new fish.

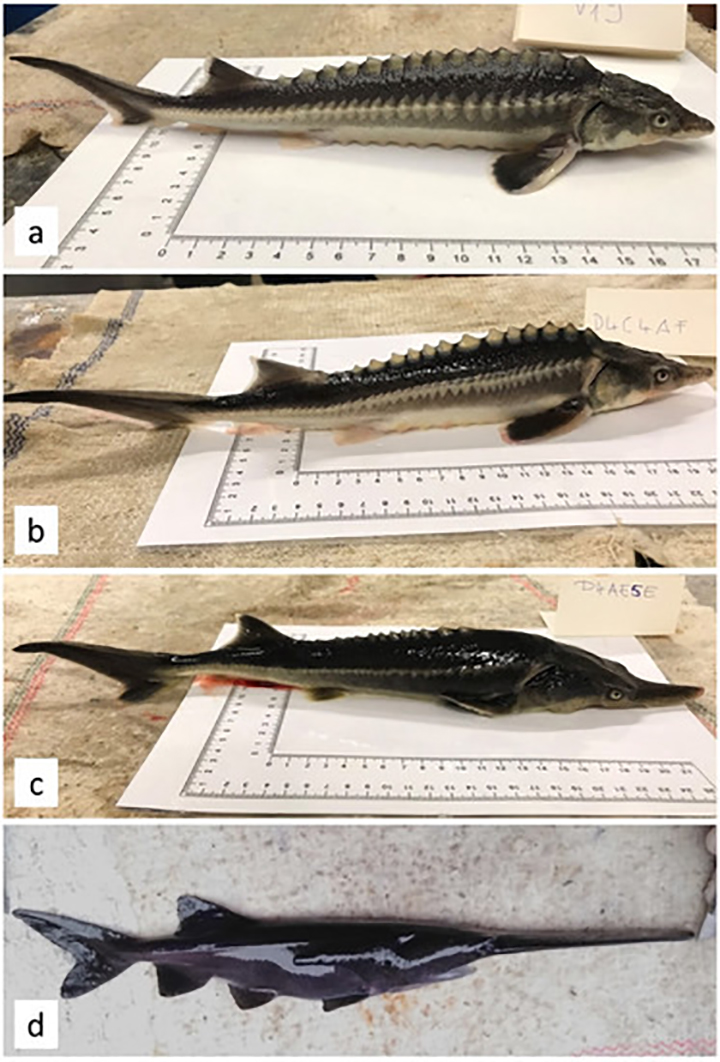

The resulting hybrids, which are being called the “sturddlefish,” have mama sturgeon’s bumpy back and carnivorous appetite, along with papa paddlefish’s fins and pointy nose, according to findings published in the journal Genes. Some look more like sturgeons, while others favour their paddlefish fathers.

“We never wanted to play with hybridization,” Dr. Attila Mozsár, a researcher and co-author of the study, told the New York Times. “It was absolutely unintentional.”

Get breaking National news

The study authors recreated the accident using eggs from three sturgeon and sperm from four paddlefish, according to the paper. Roughly 62 to 74 per cent of the hybrids survived for at least a month, and many grew into one-kilogram fish after the first year.

The hybrids took two general forms, with some favouring the sturgeon’s features and others leaning more toward the paddlefish, the paper said.

“This hybrid should die,” Miklós Bercsényi, an aquaculture geneticist who worked on the study, told USA Today. “The embryonic development should not happen.”

Solomon David, an aquatic ecologist at Nicholls State University in Louisiana, was also stunned by the discovery.

“I did a double-take when I saw it,” he told the New York Times. “I just didn’t believe it. I thought, hybridization between sturgeon and paddlefish? There’s no way.”

Researchers still aren’t certain how the fish managed to reproduce, but they suspect it has something to do with their slow evolutionary path over the last 180 million years.

“The how and the why are still open questions,” lead study author Jenő Káldy, of Hungary’s National Agricultural Research and Innovation Centre’s Research Institute for Fisheries and Aquaculture, told CNN.

The endangered American paddlefish is the only known species of paddlefish still alive, after the Chinese paddlefish was declared extinct earlier this year.

Caviar producers have been known to breed Siberian sturgeons with belugas in order to produce the tastiest possible eggs.

It’s unclear what sturddlefish eggs taste like, or if they can even produce eggs. However, researchers are hopeful that these sturddlefish can learn to eat plankton like their paddlefish mothers. That would make them useful for “adapting pond aquaculture to the challenges of climate change,” they say.

Researchers say they still have a lot to learn from their new creations. The sturddlefish are being kept at a research facility in Hungary for the time being — and they won’t be released into the wild any time soon.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.