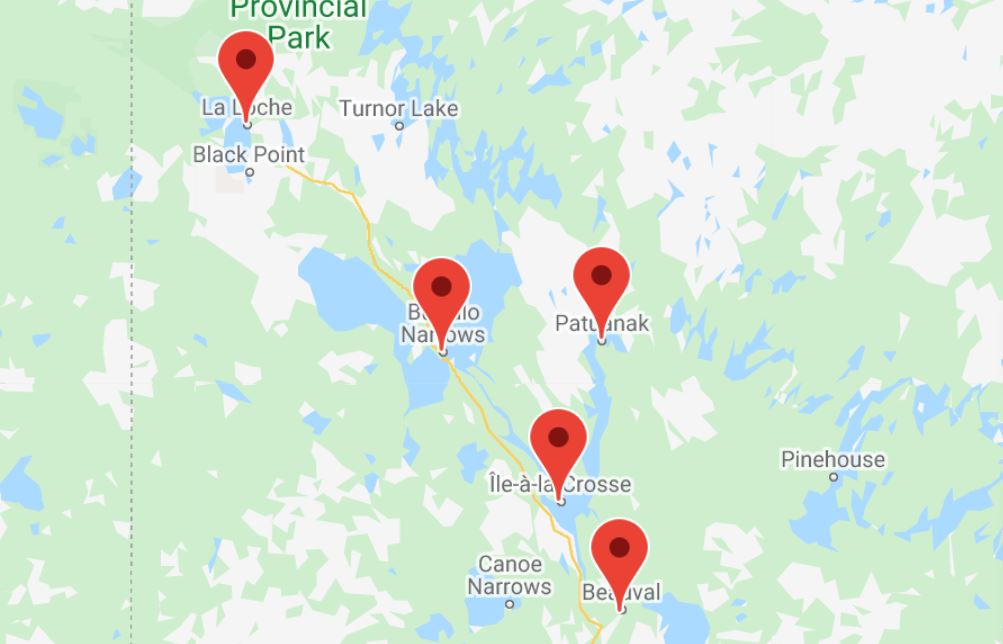

Editor’s note: The COVID-19 outbreak in northwest Saskatchewan has exposed weaknesses in the region’s fragile food system. In this three-part series, Global News will share what some local leaders, businesses and residents have said about how a month in lockdown without access to southern stores has changed how they think about feeding their communities and their families. This is part 1.

Knowing the spread of the novel coronavirus was forcing the communities of northwest Saskatchewan into lockdown, Rick Laliberte sent his son south on a grocery run.

With the Beauval General Store — the only store in the region of about 15,000 people that has a bakery and butcher department — closed for cleaning because an employee had COVID-19, its local competitor, the Beauval Northern Store, was selling out of essentials fast.

“The bread and milk disappeared off those shelves immediately,” Laliberte said.

He didn’t expect to see his son return home shortly after leaving on the errand on May 1.

What’s more, he didn’t expect him to have a $2,800 ticket for trying to pass one of the provincially-manned checkpoints that, as of April 30, were intended to control the outbreak by keeping non-northerners out and northerners in.

While that $2,800 ticket was ultimately waived, “it’s been a valuable lesson for us for the future and to prepare our communities,” Laliberte said.

The local COVID-19 outbreak, which began when an infected Alberta oilsands employee returned home to northwest Saskatchewan in early April, and the subsequent lockdown has highlighted the downside to what has become a growing dependence on southern stores for food.

But it has also encouraged many local leaders, businesses and residents to consider other options that could improve food security and sovereignty in the region over the longer term.

Communication breakdown

Ironically, Laliberte heads up the North West Communities Incident Command Centre, a collective of municipal governments, First Nations and the Métis Nation of Saskatchewan that has strived to keep the lines of communication open during the pandemic.

While Saskatchewan Government Relations Minister Lori Carr said she’s had regular contact with many area mayors and chiefs and that her staff have been involved in the incident command centre’s daily call, she acknowledged that rapidly-evolving changes to the public health order may have lacked clarity.

Get weekly health news

She said regarding food security, she was “always told that in the communities there were enough supplies on hand.”

La Loche Mayor Robert St. Pierre, whose village was a major hot spot for COVID-19 cases, said talks with the province largely focused on containing the novel coronavirus.

When it came to addressing heightened food insecurity challenges that came along with it, Indigenous organizations, social service agencies, generous fundraisers, creative residents and quick-thinking businesses stepped up.

Challenges and changes

In the north, prices are higher and incomes are typically lower. It’s a reality that means many people flock south for food.

Gary Merasty, a native of Pelican Narrows in northeast Saskatchewan and an executive vice-president of the North West Company that runs the chain of Northern Stores in the region, said as soon as the pandemic took hold, he recognized that food security was about to become an even bigger issue for the region.

“Indigenous communities are confronted with these unique challenges,” Merasty said.

“We knew we had to invest like we’d never invested before to figure out how to make this all work. It all became about keeping the doors open and keeping people safe.”

Although northern rural populations are spread out, the majority of people live close — the number of people under a single roof is high and health care is hard to access.

‘They were buying everything’

The Northern Stores made a speedy shift to online sales and implemented a version of rural delivery service. The Beauval General Store made similar changes once it was able to reopen.

Buffalo Narrows Northern Store manager Calvin Daigneault said there was the enhanced disinfecting and the 10-customer limit that was soon reduced to five at the Buffalo Narrows store. On May 4, Daigneault said he and his staff began strictly filling orders.

New customers from communities hours away began coming to the store, Daigneault said. With a ban on inter-community travel, people had to stop at the northern and southern entrances to Buffalo Narrows. There were some days he just drove back and forth between the two checkpoints dropping off groceries.

Daigneault said he could tell people were panicking and tried to instill calm using social media, posting regular updates on what was available.

“They were buying everything,” Daigneault said. “When we were closed, we sold a lot of stuff.”

With the increase in sales because people couldn’t leave the community to shop, the company facilitated short-term price drops on about 3,000 items.

Not enough food

But some people still couldn’t — and still can’t — make ends meet, said English River First Nation-La Plonge resident Candyce Paul, who also serves as a liaison of the North West Communities Incident Command Centre.

“They look in their cupboards or I see their kids looking in their cupboards and their fridge and it’s almost empty,” she said, recounting visits to friends’ and relatives’ houses.

“There’s barely anything in the cupboards on any given day.”

The Beauval General Store closed for cleaning right around “payday,” said Paul, explaining that the many residents who had been waiting for a little bit of money to grocery shop were competing for the food already flying off the shelves at the Northern Stores.

“The government shut us down and made no offer to assist,” said Paul.

“They knew the capacity, that we were in a stuck position and they did nothing. Nothing at all. They didn’t offer.”

But she quickly realized there was something she could do. As an avid gardener, married to a hunter, she has been sharing what she knows with family, friends and neighbours — and this season, there’s been a huge uptick in interest as people start returning to the land to counter food insecurity.

To learn more about the food initiatives in northwest Saskatchewan, stay tuned for part 2 on Tuesday.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.