Tensions over the Coastal GasLink rose once again this week, as the RCMP enforced a court injunction near the construction site of the natural gas pipeline in northwestern British Columbia.

The Wet’suwet’en Nation, unceded territory not covered by treaty, has long opposed the project, saying governments do not have the consent of hereditary chiefs.

The situation has been escalating since Dec. 31, when the B.C. Supreme Court granted Coastal GasLink an expanded injunction.

Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs responded by issuing the company an eviction notice in early January, saying the company was violating traditional Wet’suwet’en laws.

On Thursday, six people were arrested at the pipeline construction site by RCMP who were trying to clear the area. RCMP said they had delayed enforcing the injunction for weeks to seek a peaceful resolution, but without one, they had no choice but to follow the court’s orders.

The issue spilled over into other provinces, leading to protests in Ontario that led to train delays on Friday.

Here’s a look at the ongoing dispute.

What is the pipeline project?

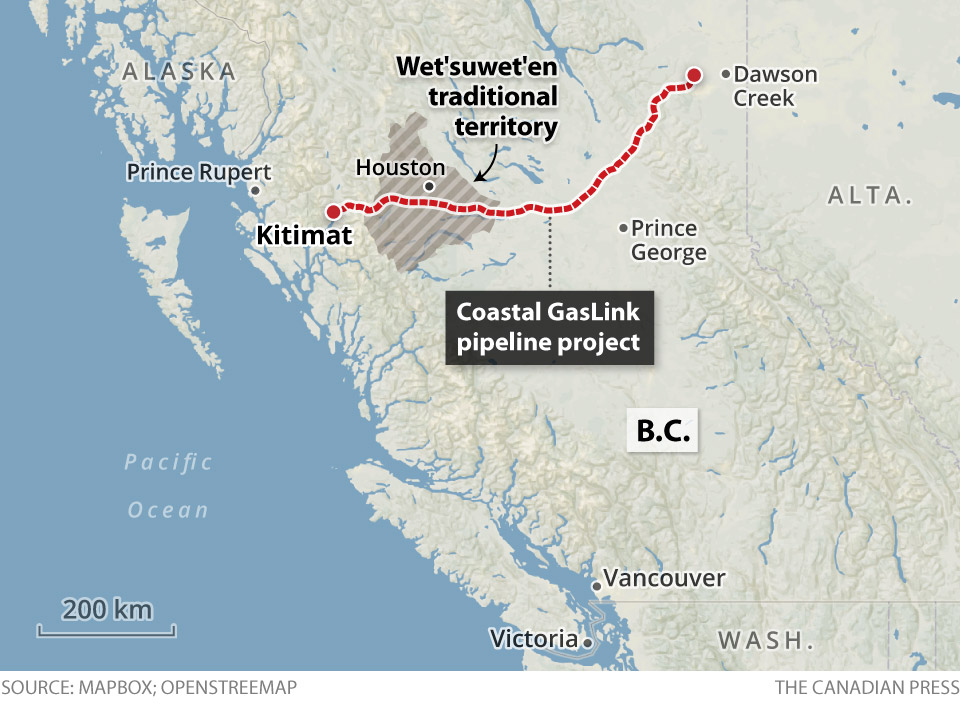

The $6.6-billion, 670-kilometre pipeline is intended to carry gas from northeastern B.C. to a massive LNG export plant being built near Kitimat.

Coastal GasLink says it has signed agreements with the elected councils of all 20 First Nations along the path of the pipeline — including the Wet’suwet’en.

A look at Wet’suwet’en Nation

Get daily National news

The Wet’suwet’en Nation, which consists of five clans, is situated near the Bulkley River in northwestern B.C.

The nation’s hereditary chiefs have repeatedly said they do not want a pipeline.

What is unceded territory?

The Canadian government has recognized that all land in the country was originally owned by Indigenous People. Brenda Gunn, an associate professor at the University of Manitoba, explained that before Canada can rightfully claim the ability to make decisions about the land, it has to take ownership of it.

“In the Wet’suwet’en case, the Wet’suwet’en have never ceded their right to the Canadian government,” Gunn said.

Gunn added that the process to take ownership of lands usually involves treaties, which is why Wet’suwet’en is not covered by a treaty.

In other words, the nation has never officially surrendered its Aboriginal title — its right to the territory.

A key factor in Indigenous communities being able to hold on to their Aboriginal title is physically occupying that land, Gunn explained.

“It was the Canadian court that said the Wet’suwet’en must show ongoing occupation of their land in order to prove Aboriginal title. Both the Canadian and British Columbia governments are aware of this requirement,” Gunn said.

Hereditary chiefs and band councils

While hereditary chiefs are calling on an end to construction, Coastal GasLink president David Pfeiffer maintains the project has the support of Indigenous leaders.

In an open letter on Thursday, Pfeiffer said the company is proud of its support from all 20 elected Indigenous governments along the pipeline path and is disappointed that it has not “found a way to work together for the benefit of the Wet’suwet’en people.”

That’s because the project has the support of the elected band council — but not hereditary chiefs.

University of Toronto professor Jeffrey Ansloos, who is a member of the Fisher River Cree Nation, explained to Global News that hereditary chiefs are a form of Indigenous governance that precede British colonization.

“These are, in a very real sense, governments with distinct law, with distinct traditions, rule, regulations and protocols for how communities are governed,” Ansloos explained.

Band councils, in contrast, are a structure that was introduced by the federal government through the Indian Act.

“Councils are elected; they are a structure that is not necessarily the same governance structures that would have preceded Canadian colonization.”

He noted that how these two groups work together can vary among First Nations communities.

Naomi Sayers, an Indigenous lawyer from Garden River First Nation in Ontario, pointed out consultations don’t always equal consent.

“In this case, the band council is saying ‘we were consulted and we agree,’ and the hereditary chiefs are saying ‘we do not consent,'” Sayers said.

There can also be disagreement within Indigenous communities on which group should make which decisions, she noted.

“You have diverse viewpoints and different concerns. When some people don’t feel like their concerns are being heard, they will rely on the other processes.”

B.C. government response

The disagreement consists largely of which groups the government should consult with for such projects.

B.C. Premier John Horgan has said the Coastal GasLink project will go forward, even if hereditary chiefs are not on board.

“The rule of law applies in British Columbia,” Horgan last month, following the court decision.

“All the permits are in place for the project and the project will be proceeding.”

Horgan said he doesn’t think hereditary chiefs have the power to stop the project.

“I don’t believe they do, and more important, the courts don’t either,” Horgan said.

“In this instance, the courts have determined this project can proceed and it will proceed.”

Talks between hereditary chiefs and the province have not been successful. A planned week of talks between the province and the chiefs broke off Tuesday after two days of discussions, with the Wet’suwet’en saying no deal could be reached unless the province pulled its permits for the project.

— With files from Global News reporters Richard Zussman, Sean Boynton and The Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.