Editor’s note: This story has been updated since it was originally published on Jan. 27.

As China first announced the outbreak of a viral pneumonia in December, authorities said there was no “clear evidence” of human-to-human transmission and most patients had been exposed to a food market in the city of Wuhan.

“Most of the unexplained viral pneumonia cases in Wuhan this time have a history of exposure to the South China seafood market,” the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission said in a statement.

“No clear evidence of human-to-human transmission has been found.”

But a new study published by Chinese researchers in the Lancet on Jan. 24, and reported on in Vox, The New York Times and other outlets, appears to contradict some of those assertions and offers a different version of the early days of the outbreak.

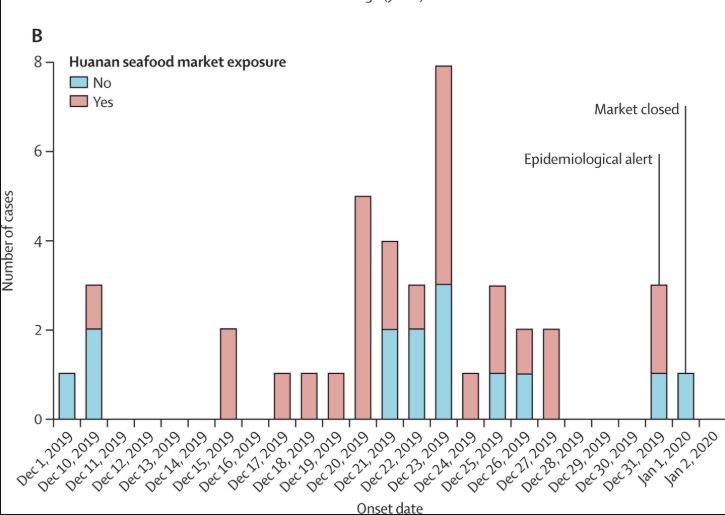

Researchers found that of the first 41 confirmed cases of the virus, nearly half were 49 years old or younger and roughly a third had not been exposed to the Huanan market identified, suggesting that the virus may have been transferred from person to person in early December.

“The number of deaths is rising quickly,” the researchers wrote. “We are concerned that 2019-nCoV could have acquired the ability for efficient human transmission.”

Get weekly health news

Roughly 15 per cent of those first 41 people died, according to the study, and the first patients were admitted to hospital in early December, more than a month before Chinese authorities closed the wild animal market and quarantined Wuhan and other neighbouring cities in Hubei province.

Steven Hoffman, director of the Global Strategy Lab and a global health professor at York University, said the study raises questions about whether some of the initial concerns coming out of China about the virus were “downplayed.”

READ MORE: Health officials urge Canadians to get coronavirus information from credible sources

“The first 41 cases does look very different than what China was reporting at the time,” Hoffman told Global News. “In any public health response, one of the most important things is the co-operation of the public.

“The public will only co-operate if they think the health authorities can be trusted.”

Experts with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also publicly criticized what they called a lack of data from China about the Wuhan coronavirus, which was hindering international efforts to stem the outbreak.

“This is Epi 101,” said Dr. William Schaffner, medical director of the U.S. National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. “I don’t want to denigrate our Chinese colleagues, but when information is not presented clearly, you have to wonder.”

READ MORE: How to protect yourself from coronavirus

During the 2003 SARS outbreak, China was accused of concealing information about the number of illnesses and putting economic considerations before the lives of citizens. In some cases, patients were hidden in hotels and obscure hospital wings and even driven around in ambulances to avoid detection by World Health Organization experts.

The virus eventually killed 774 people and infected more than 8,000 — including 44 in Canada.

As of Monday, there are more than 2,800 cases of 2019-nCoV across China and 80 deaths so far. Cases of the new coronavirus have also spread to more than a dozen other countries, including five cases in the U.S. and two in Canada.

Other explanations for the inconsistencies between the Lancet study and Chinese officials could be what the New York Times identified as China’s rigid bureaucracy, in which “rigidly hierarchical bureaucracy discourages local officials from raising bad news with central bosses.”

READ MORE: 2nd ‘presumptive’ coronavirus case reported in Ontario

Zhou Xianwang, mayor of Wuhan, has acknowledged criticism over his handling of the crisis, admitting that information was not released quickly enough.

“We haven’t disclosed information in a timely manner and also did not use effective information to improve our work,” Zhou told the Chinese state broadcaster CCTV. He added that his government was obliged to seek permission from the People’s Republic of China before fully disclosing information about the virus.

However, Hoffman said there’s reason to believe that China is now offering full disclosure in its reporting about the virus.

He pointed to a public statement on Jan. 20 by Chinese President Xi Jinping that called for all governments to “put people’s lives and health first.”

“Party committees, governments and relevant departments at all levels must put people’s lives and health first,” Xi said. “It is necessary to release epidemic information in a timely manner and deepen international co-operation.”

The ruling Communist Party’s central political and legal affairs commission also issued a warning that echoed China’s failings during the SARS outbreak.

“Whoever deliberately delays and conceals reports will forever be nailed to history’s pillar of shame,” the warning said.

David Heymann, a doctor who headed the WHO’s global response to SARS in 2003, told the Associated Press that it appears the government is reporting cases of the new virus as soon as they are identified.

“I think it’s working pretty well compared to what happened initially in SARS,” Heymann told the Associated Press.

Hoffman said that from all indications, “we are now getting full information from China.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.