Three months before he boarded a plane in Cairo and six months before he made a refugee claim in Toronto, Canadian security officials deemed retired Brig.-Gen. Khaled Saber Abdelhamed Zahw “inadmissible” to Canada because of national security concerns.

Zahw was a “high-ranking” member of Egypt’s military when it orchestrated a coup of President Mohamed Morsi’s government in 2013, according to the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA).

An inadmissibility finding would keep most people out of Canada, but it didn’t stop Zahw and his wife from obtaining valid visitor visas from the Canadian embassy in Egypt in April 2015.

This is because, according to internal government documents obtained by Global News, Canada has a secret program that allows certain “high-profile” foreign nationals who would otherwise be barred from entering the country due to national security concerns, war crimes, human rights violations and organized crime to be granted special “public policy” entry visas so long as it is in Canada’s “national interest.”

But exactly what “national interest” means in relation to this policy and how the government decides who gets this kind of visa is unclear.

That’s because there’s almost no information available about the program, and the government refuses to answer questions.

Details of Zahw’s immigration file, including internal government documents detailing the secretive visa policy, were submitted to the Federal Court when Zahw challenged the government’s efforts to block him from making a refugee claim.

Zahw sponsored by National Defence

In Zahw’s case, visitor visas were issued after a senior official from the Department of National Defence (DND) in Ottawa wrote a letter to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) saying Zahw and his wife should be given visas to avoid upsetting Canada’s relationship with Egypt’s military.

This type of “national interest letter” can be issued by any federal department or the head of a Canadian mission abroad, such as an ambassador or high commissioner, according to an unpublished government “operational bulletin” contained in Zahw’s Federal Court file.

These letters, the bulletin shows, are valid for up to 24 months, are good for multiple trips to Canada — including personal and official travel — and are issued when the CBSA has completed a security screening and determined that the “risk/danger” to Canada is low.

“It is in our interest to maintain constructive relations with members of the Egyptian military as these relationships enable execution of Canadian Armed Forces operations in the region, most notably Operation CALUMET,” read a letter sent by DND Assistant Deputy Minister for Policy Gordon Venner prior to Zahw being given a visa.

The government, meanwhile, will not provide any details about the visa policy or the criteria it uses to decide who is given this kind of special exemption.

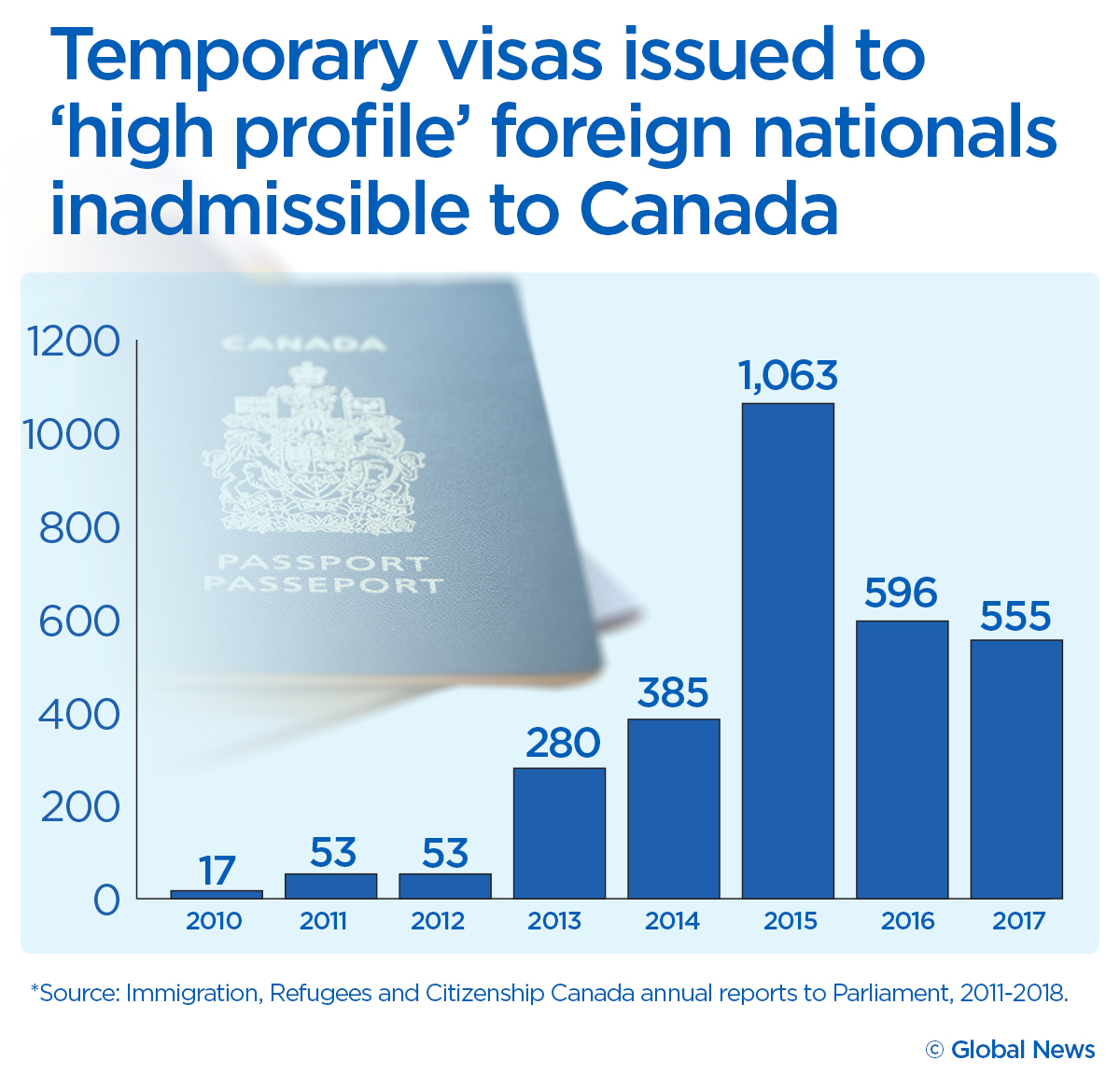

A review of annual reports submitted to Parliament by IRCC — which contain few details about the policy — shows that 3,000 of these visas were issued between 2010 and 2017.

The government would not say how many of these visas were issued for each category of inadmissibility, nor would it say what countries the recipients came from.

“The information requested in this media request is exempt under section 15 of the Access to Information Act, as it could be injurious to the relationship with our international partners,” said IRCC spokesperson Rémi Larivière in a written statement.

Get daily National news

The only other details the government would provide about the policy is that it was created to “advance Canada’s national interests while continuing to ensure the safety of Canadians” and that recipients of these special visas can work, study and travel in Canada.

Zahw likely unaware of exemption

In January 2015, the same month he reportedly retired from Egypt’s military, Zahw and his wife applied for permission to travel to Canada.

Immigration records show their application was then transferred to the CBSA’s national security screening division, at which point Zahw was flagged for inadmissibility.

How DND became aware of Zahw’s application, and that it could be rejected, is unclear.

It’s also unclear if Zahw knew he could have been barred from entering Canada or that he was given a special kind of visa exempting him from national security concerns.

The government’s internal operational bulletin says immigration managers and visa officers at foreign embassies — those who typically approve visas — may notify federal departments of cases in which refusing a visa could have “national interest considerations.”

Senior officials from these departments may then decide to write a national interest letter “sponsoring” the applicant and requesting that IRCC waive any security concerns.

According to the bulletin, the final decision on whether to issue this type of visa is made at the most senior levels of IRCC after each case is evaluated.

The bulletin also says public policy visas have the same physical appearance as ordinary visas and that recipients, such as Zahw, should not be notified when this type of visa is used.

The government would not comment on Zahw’s case specifically.

It did, however, say IRCC also has the power to grant temporary resident status to non-high-profile foreigners barred from entering Canada due to national security concerns, human rights violations and organized crime.

These cases are approved at the same decision-making level of IRCC as the public policy visas — although the process outlining how these decisions are made is publicly available.

Refugee claim triggers concern

Had Zahw and his wife visited their family in Brampton and returned to Egypt, immigration officials would not have revealed that his military past was a concern.

It wasn’t until the couple made refugee claims — alleging Egyptian intelligence agents mistreated them because Zahw opposed the 2013 coup — that Zahw’s rank as a brigadier-general was disclosed as a problem.

According to government lawyers, Zahw was allowed to visit Canada temporarily, but once he made a refugee claim — meaning he wanted to stay permanently — his special visa waiving national security concerns was no longer valid.

It was in support of this argument that lawyers for IRCC revealed the DND national interest letter and the internal bulletin describing the government’s public policy visa program, records from the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB) show.

But Zahw disagreed with this argument, saying the government’s position made no sense.

The fact he was allowed to enter Canada after being assessed by the CBSA, Zahw argued, proved that he was not a threat and that any security concerns the government might have had were dealt with when he was issued his initial visitor visa.

Zahw, who worked as a telecommunications expert within the military, also argued that he was not dangerous and did not play a direct role in the 2013 coup.

But the IRB and Federal Court rejected these arguments, ruling that there is a distinction between coming to Canada temporarily versus permanently and that it made no difference whether or not Zahw was directly involved in the coup.

Under Canadian law, the government only has to prove there are “reasonable grounds to believe” someone is a member of an organization that engages in dangerous acts — such as subverting a government by force — in order to find them inadmissible on national security grounds.

Since Zahw’s position within the Egyptian army was never in dispute, the Federal Court rejected his application to proceed with an asylum claim.

Policy is an ‘insidious’ example of secrecy

While he does not have permission to speak about the case, Zahw’s lawyer, Hart Kaminker, told Global News he thinks the government’s secretive visa program is “troubling.”

This, he said, is because so many details about the policy are kept secret and because it creates a double-standard where “high-profile” people the CBSA thinks should be barred from entering Canada are let in while those who do not have the same power, money or influence are kept out.

Lorne Waldman, an immigration lawyer who specializes in human rights law and national security cases, has reviewed the operational bulletin obtained by Global News and says the policy is an “insidious” example of government secrecy.

He says it’s clear from the bulletin that the purpose of the program is to avoid embarrassing foreign governments — many of which are bad actors — by secretly approving visas for people who are or could be complicit in the most serious kinds of security risks, such as torture, war crimes, terrorism or human rights abuses.

The fact applicants don’t know they’re given a special visa makes the program even more troublesome, Waldman said. By staying silent about a person’s nefarious past, Canada is signalling to foreign governments and individuals that their actions are OK — even when they’re not.

“Where there’s a political interest to issue a visa, they’ll issue it,” he said.

And if, as the government insists, this program is necessary for maintaining Canada’s national interests, then the way these decisions are made and who makes them should be out in the open and subject to independent oversight, Waldman said.

“By doing it in a secretive, sort of clandestine manner, they’re hiding from the public the fact that they’re even engaging in this,” he said.

“This is extremely concerning, it’s extremely undemocratic… and Canadians have a right to know.”

Comments