When Sara was pregnant with the first of her three children, her husband told her she wouldn’t have to worry about going back to her career in human resources.

His message was clear, she says: “I do the money, you do the children.”

At the time, that arrangement seemed fine to Sara. That’s the way her parents’ relationship had worked, she says. (Global News is not using her real name due to the sensitive nature of her case.)

Sara expected to be fully absorbed in child-rearing, and her husband, a high-flyer in the insurance industry, made more than enough to support their growing family. Besides, Sara initially kept working part-time, taking on a teaching job at a post-secondary institution after her first maternity leave.

It wasn’t until two years later, when she became pregnant with her second child and switched to teaching only one course per year for much lower pay, that money started to be tight.

But when Sara asked her husband to give her cash for groceries, clothing and other day-to-day expenses for herself and the kids, she says initially he would only give her $600 a month.

Any time she asked for more money, he would yell at her, accusing her of wasting it and telling her she couldn’t be trusted with it, she says. If she brought up returning to work full time, she got a similar reaction. Their bank accounts were separate, so Sara had no real sense of the family’s finances.

Although her husband was never violent with her or the children, he was prone to screaming, shaming and hitting furniture in fits of anger, she says.

“I was scared of him.”

Abuse often involves money, with one partner monopolizing financial resources as a way to exercise control in an intimate relationship. It’s a specific type of abuse that advocates say makes it harder for victims to leave and rebuild independent lives but remains a woefully understudied issue.

Financial abuse often occurs alongside violence and other types of coercion and exploitation. While men can also experience it, 80 per cent of intimate partner violence victims are women.

Around half of women staying in shelters have experienced financial abuse, according to Statistics Canada data. U.S. studies, however, suggest the overlap with domestic violence may be much more significant, finding between 94 and 99 per cent of women in abusive relationships have been subjected to some form of financial abuse.

“We hear it consistently, from survivors themselves (and) from service providers, just how prevalent financial abuse is,” says Lieran Docherty, program manager at the Woman Abuse Council of Toronto (WomanACT) and co-author of a recent report on financial abuse titled Hidden in the Everyday.

Financial abuse happens at all income levels, the report found. Household incomes at the time of the abuse ranged from under $25,000 to $150,000 a year, according to interviews with 14 survivors conducted by researchers at WomanACT.

While Sara’s family led an upper-class lifestyle with a $100,000 luxury car and lavish vacations every year, she was constantly counting pennies.

To save money, she stopped wearing makeup, started shopping at second-hand stores and learned to make the most of coupons, she says.

“There were two years I went without a haircut.”

The abuse can take many forms, advocates say. Often, it involves abusers exercising complete control over household financial flows, with women like Sara kept in the dark about the family’s assets and liabilities and unable to access or open bank accounts.

Some women in the WomanACT study reported their partners would regularly steal cash from their wallets, seize their paycheques and credit cards and spend tax refunds and government benefits, including the Canada Child Benefit, on themselves. In other cases, abusers prevent women from earning an income by undermining their employment or preventing them from getting a job or going to school.

Get weekly money news

One survivor interviewed by WomanACT recalled her partner demanding money from her while at the same time hindering her ability to earn it.

“Even though he wanted my money, he would, like, lock me — literally, lock me in my bedroom and stay at the door — and I couldn’t go to work so I ended up losing my job.”

Victims of financial abuse often end up in debt, advocates say. Sometimes, that’s because they have no choice but to borrow money to pay for necessities for themselves and their children.

When Sara’s middle child went through two shoe sizes in five months during a growth spurt, she lay awake at night thinking about how to pay for extra pairs of indoor and outdoor shoes for school, boots and skates. She told the kids not to mention the additional shoe-shopping to their father.

“We had to keep things secret from daddy because, otherwise, he’d get mad as hell,” she says.

Sometimes, Sara says, she was so desperate she turned to a line of credit she had had since before getting married. Once, she says, she was forced to ask her parents to help her pay off the balance. Not wanting to do that again, she says she had to make the allowance from her husband stretch in order to make monthly partial payments to the credit line as well.

Over time, Sara managed to gradually increase the allowance to $2,500 a month as her husband’s salary grew. By that time, though, servicing her debt was costing her around $1,200 a month. By that point, the rest of the money had to cover not just groceries and clothing but also all expenses related to the holidays, birthdays, special occasions and entertaining, she says.

“I was always worried about the debt and running out of money, but I found that I kept piling on more debt just to make it appear to him like I had enough to manage.”

Sometimes, it’s the abuser who takes on debt in the victim’s name.

One victims’ services worker who spoke to WomanACT recalled a client who was left with $10,000 in parking fines racked up by her partner on a vehicle registered in her name.

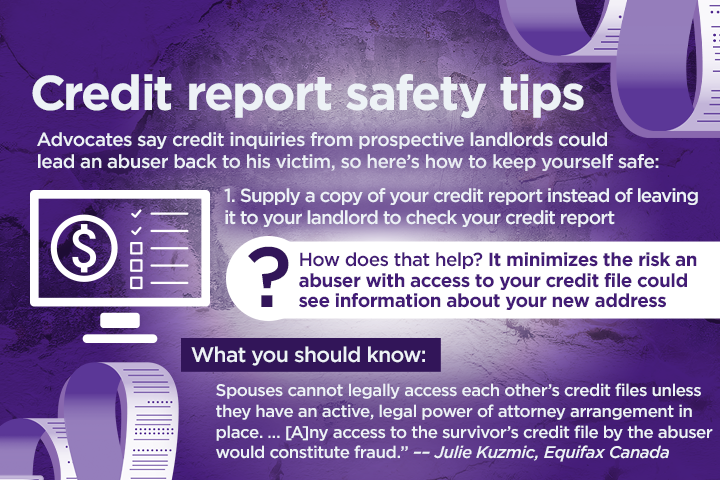

Unpaid debts, however they come to be, often leave survivors’ credit scores in tatters, which exacerbates victims’ already difficult attempts to secure housing if they leave their abusers.

“If you don’t have credit, you can’t get a house,” says Angela Marie MacDougall, executive director of Battered Women’s Support Services in Vancouver (BWSS), noting that landlords often check prospective tenants’ credit scores.

Proving your domestic partner committed credit fraud can be complex, Docherty says.

Often, survivors don’t even attempt to challenge loans and credit cards obtained without their knowledge or consent, advocates say, they simply resign themselves to slowly rebuilding their credit once they have left the relationship and regained control of their credit file.

It’s a process that can take up to several years, says Kim Pentico, director of economic justice at the U.S.-based National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV).

To help women boost their score, the organization has started a micro-lending program through which survivors can apply for a $100 loan and repay it over a 10-month period, with NNEDV reporting each payment to the credit bureaus.

None of the advocates to whom Global News spoke were aware of a similar program currently running in Canada.

Equifax Canada is having “ongoing conversations” on the issue of financial abuse, which has also emerged as a problem in cases of human trafficking, says Julie Kuzmic, director of consumer advocacy at the credit bureau.

TransUnion, the other major credit bureau in Canada, did not comment.

Victims of financial abuse also have to contend with little support from the government, domestic violence counsellors say.

In Vancouver, affordable child-care options are the “biggest barrier” to survivors’ ability to get a job and an income of their own, MacDougall says.

In Ontario, the income threshold to receive legal aid is so low that many victims of financial abuse don’t qualify for it even if they have limited access to household finances, Docherty says. The current threshold for victims of domestic abuse is $22,720 for an individual and $32,131 for couples. Victims who are not eligible for the service often don’t follow through with family law proceedings or end up representing themselves, she says.

And Ontario Works, which provides financial assistance to low-income individuals and families, requires that couples apply jointly after only three months of living together, something support workers told WomanACT can worsen a woman’s financial dependency on her abuser.

Still, people can escape financial abuse.

Victim support services can help come up with an exit strategy that minimizes safety risks to women and their families. (However, advocates urge victims to use caution when searching for such services online as abusers can often track their partners’ online activities on their personal devices.)

Women who are leaving an abusive relationship should take at least half the money in any joint accounts, BWSS suggests.

“Many women survivors of violence who have had to flee their home report being surprised to discover their partner immediately drained any joint bank accounts,” the organization warns.

Another important step toward self-sufficiency is learning about money, from budgeting to investing and risk management, says Tina Tehranchian, a certified financial planner at Assante Wealth Management.

It’s essential that women understand household finances and the family’s net worth, she says.

It took Sara years to realize she had a right to know all that.

She says that when she realized what her husband was doing was financial abuse — it was a psychologist who told her — she started pushing back and he left.

Now that she is separated and receiving spousal support, Sara finally has enough money not just to take care of herself and her children but to go back to school to update her skills and resume her work in human resources, something her husband always resisted.

She has applied to graduate school and is also setting up a consulting business, she says.

Sara is savouring her newfound financial independence, especially her new car.

“When I took that car out on the freeway and realized I could make the decision to buy it and that it was mine, I cried,” she says.

Only a few months old, the car already has 21,000 kilometres on it.

“It’s my freedom.”

To read the full Broken series, go here.

For a list of resources if you need help, go here.

Our reporting doesn’t end here. Do you have a story of violence against women, trans or non-binary people — sexual harassment, emotional, physical or sexual abuse or murder — that you want us to look at?

Email us: Erica.Alini@globalnews.ca

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.