Surrounded in the shrinking territory of the Islamic State nine months ago, Safraz Ali fled with his wife, walking to a military checkpoint where soldiers asked their nationalities.

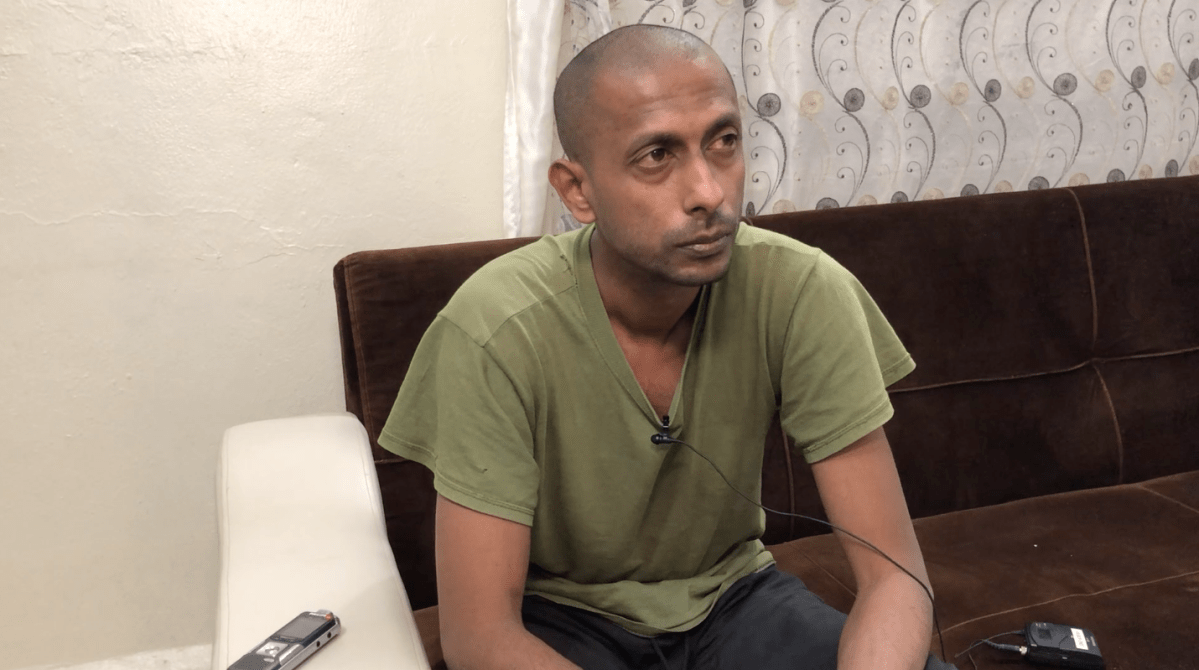

“I said, ‘Canadians,’” Ali told Global News at a military base in northern Syria, where he was being held at a prison for ISIS suspects.

In an interview, Ali revealed that ISIS had tried to recruit him to return to North America to conduct terrorist attacks. But he said he had refused.

“I don’t believe in foreign attacks,” he said.

For declining to participate in the plot, Ali said he was jailed and tortured by ISIS.

“Saf’s one of the good ones,” said his wife, Kimberly Polman, a Canadian who married him in the ISIS capital of Raqqa and is also detained by Kurdish forces in Syria.

Slender and clean-shaven, Ali is a puzzle: a former University of Calgary student who left home to live in ISIS territory but claims he was never a member of ISIS.

His case highlights the challenges governments face following the collapse of ISIS six months ago as they are asked to repatriate and prosecute their citizens held in camps and prisons in northern Syria.

What, exactly, was Ali’s role in ISIS? If he were sent home, could he be charged? Should he be? Is there evidence he was more involved than he admits? Is he even really a Canadian citizen?

While some of those captured in Syria openly acknowledge their contributions to ISIS, the involvement of others, like Ali, is less clear, making it more difficult to know how to deal with them.

“At least from our short interaction with him, he seems to have gone there with a kind of naïve sense of contributing against the Assad regime,” said Prof. Amarnath Amarasingam, who also met with Ali, along with national security lawyer Leah West.

Ali described becoming disillusioned with ISIS almost immediately after arriving in Syria as well as his attempts to avoid joining a fighting group and his imprisonment and torture for defying ISIS.

“Whether any of that is believable and whether there’s evidence that he did other things while here is still kind of up in the air,” said Amarasingam, a Queen’s University professor.

He faces no charges in Canada. Global Affairs Canada will only say it is aware that Canadians are detained in Syria.

Days before the Turkish military invaded northern Syria, throwing the fate of ISIS detainees into question, Ali recounted how he was born in Port of Spain, Trinidad, and later moved to Calgary, where his father was studying.

When his parents split up, Ali went back to Trinidad with his mother but returned to Canada to attend the University of Calgary. Two of his brothers were born in Toronto and still live there, he said.

Get breaking National news

“I could say I have Canadian … and I have Trinidad nationality,” he said.

Fresh from a breakup, he said he decided to join four Trinidadian friends who were on their way to the Islamic State with their families.

“I said maybe there’s a better meaning for me,” he said. “I didn’t come here to be a fighter.”

Rather, he said he felt compelled to do something about those suffering in the city of Aleppo.

“When the people cry for help, as a Muslim, you’re supposed to help,” Ali said.

He said he was told that in Syria, “everything is good, you know, these people practising their religion and everything.” But that wasn’t what he found when he arrived from Turkey in March 2015.

For the first two months, Ali said he was “put in a place” where “they give you courses, you have to learn religious stuff,” adding that because of his passport, he went by the name Ahmed Kanadi, Arabic for Ahmed Canadian.

Once through training, ISIS told him to find an English-speaking fighting group because his Arabic was weak. But instead, he spent “five months just doing nothing,” he said in the interview.

Eventually, he was caught, jailed for five days as punishment and assigned to “ribat,” or guard duty, on the Turkish border north of Aleppo.

He denied enforcing the harsh ISIS rules on the Syrians he encountered.

“People have to want something, you don’t force it to them,” he said.

He acknowledged carrying a weapon at the time, saying it was mandatory, but that “a weapon don’t kill people, people kill people, understand?”

Accused by ISIS of being a U.S. spy, Ali said he was imprisoned in Manbij. He did not elaborate but alluded to a video posted on YouTube in June by the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism.

The video showed a man with a blurred face, who it called “Abu Henricki,” describing how ISIS had tried to recruit him to return to North America to conduct “financial attacks to cripple the economy.”

“That’s me,” Ali told Global News. “I don’t believe in these acts. It cost me five months and then it cost me a lot of pain.”

Upon his release from prison, Ali went to Raqqa, where he said he continued to do nothing and was “just staying in an apartment, just trying to recuperate from the prison.”

He wanted to marry an English-speaking woman and heard about Polman, a Muslim convert who left Vancouver in 2015 and was smuggled into ISIS territory after corresponding with a man she met online.

“I could relate to her, talk to her,” Ali said.

They were married, but Ali became ill and was diagnosed with Crohn’s, an inflammatory bowel disease. A doctor at the Raqqa hospital gave him a letter excusing him from his duties so he handed in his gun, he said.

“I just wanted to live a good life with my wife,” he said.

He claimed he continued to do nothing but live in ISIS territory as a non-ISIS member until 2017 when masked men came to his door at 10 p.m. to arrest him. Polman was also taken into custody.

The couple was imprisoned on the grounds they had wanted to leave ISIS territory, something he said Polman had expressed openly.

“She’s very outspoken, and what she sees wrong she will say, and she never hid the fact she wanted to leave,” Ali said.

Another Canadian was behind their arrest, he said. Farah Mohamed Shirdon, who went by Abu Usamah, was “one of the heads of security.” His job was to detain those trying to leave, according to Ali, who said the couple was told Shirdon had ordered their arrest.

READ MORE: ‘It’s craziness here’ — Kurdish forces struggle to contain world’s unwanted ISIS prisoners in Syria

Life was difficult after they were released with a warning that they would be executed if they tried to leave, he said. Polman miscarried five months into her term, he said. Meanwhile, ISIS was losing Raqqa to the Syrian Democratic Forces and coalition forces.

Like the ISIS leadership, they fled the city and went southeast to Al Mayadin, then kept moving towards the Syrian-Iraqi border, looking for a smuggler to get them out, Ali said.

Eventually, there was nowhere left to go, and they decided to try to get to a point where they could find a smuggler, but instead they came to a security checkpoint.

“They said, ‘Where are you from?’ I said, ‘Canada,’” Ali said.

Polman said Ali could have left sooner but “he was trying to get a lot of the other people who stayed back, to try to get them to come out.”

She said ISIS took the passports of those arriving in its territory and she had never seen Ali’s.

“What, exactly, his documentation is at this point, I don’t think Canada’s stripped citizenship,” she said.

They were passed to American troops, who took their fingerprints. Ali and Polman were separated and have not seen each other since. She is at a camp for female detainees.

“I’m not a radical, I’m not an extremist. I don’t believe in acts of slavery or foreign attacks, which I am against. And if I could work against these people, I would work against these people,” he said.

He spoke about returning to Canada, getting a degree in history and finding a job building oil pipelines. He said he was aware that returning to Canada could mean arrest and more prison time.

“It may be better for us,” he said. “Prison’s not good for anybody, but at least I could see my wife somehow and I could talk to her, and maybe we both could do some studies there. Knowing that she’ll be close by is very much what I want.

“I just want a quiet life.”

Stewart.Bell@globalnews.ca

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.