During the counter-terrorism raids in Kingston on Jan. 24, tactical officers watched over snowy neighbourhoods, investigators carried evidence bags out of homes and Mounties in blue serge announced charges from a podium.

But out of sight, a very different fight against terrorism is getting underway — one that aims to knock Canadians on the fringes of radical violence off that trajectory before they start to build bombs and scout targets.

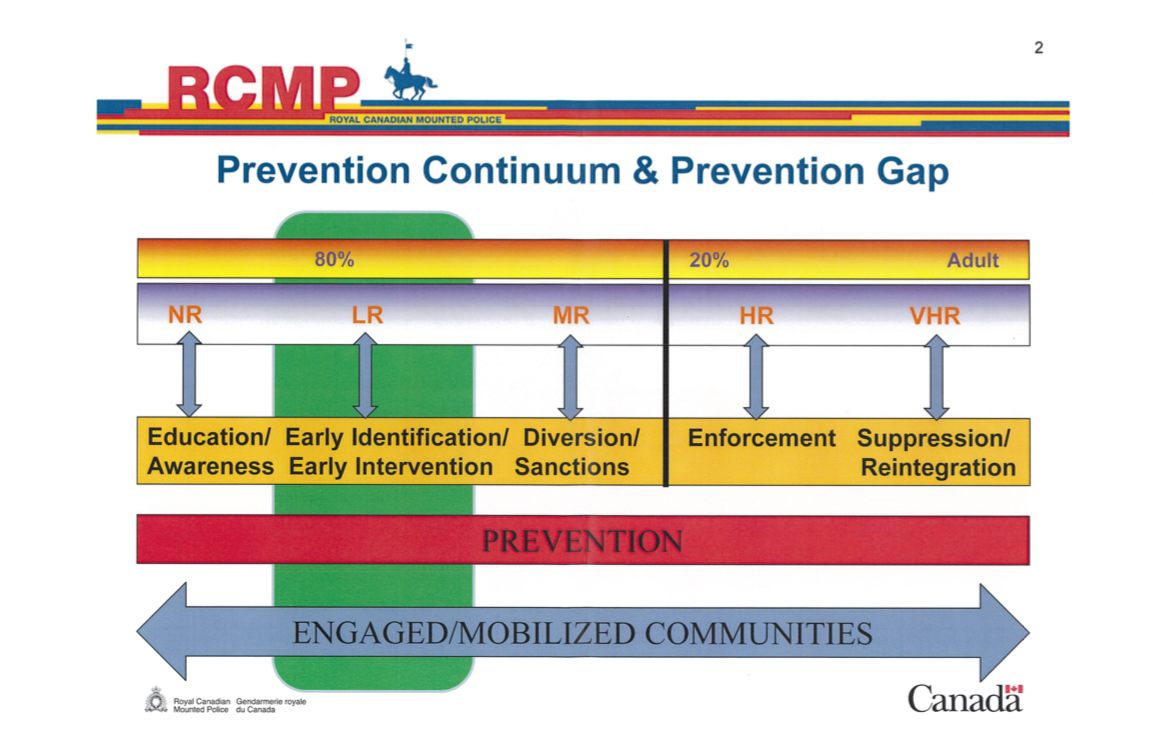

Drawing on the same kinds of strategies used to combat drugs and gangs, Canadian police are now aspiring to prevent terrorism sooner by identifying those in the initial stages of radicalization and steering them to help.

“There’s a lot of people doing a lot of great work behind the scenes,” RCMP Supt. Lise Crouch, who heads the Integrated National Security Enforcement Team in the Toronto region, told Global News.

WATCH: New Zealand shooting: Thousands pack Dunedin stadium in vigil for the fallen

The deadly shootings at two New Zealand mosques by an alleged racist, anti-immigrant terrorist have once again underscored the horrific consequences of extremism left unchecked.

The incident has also reinvigorated debate about how to prevent such attacks.

In an interview at the Toronto INSET office, Supt. Crouch discussed for the first time how the RCMP is attempting to curb terrorism by intervening earlier.

“I think it’s important that this story is told,” said the veteran counter-terrorism officer, who has been helping set up the RCMP’s violent extremism prevention program around Toronto.

WATCH: How the RCMP intends to handle returning foreign fighters

The concept is straightforward: train frontline officers and community members to recognize the signs of violent extremism so that problems can be spotted and dealt with before they get out of hand.

Those on the cusp of radicalization might get referred to social service agencies, mental health treatment, clerics, reformed terrorists and anyone else in a position to help, thereby defusing emerging extremists.

It’s not for everyone.

“There are some people who we will just have to continue to investigate because they are a significant threat,” the superintendent said.

But she said intervening sooner could reduce extremist violence in the long run and free police to focus on more urgent threats to national security.

“So that’s what we’re working towards,” she said. “There have been successes already.”

Without naming the suspect, she described how police had received information that someone in Toronto had been messaging on social media about joining ISIS and attacks in Canada.

Police launched an investigation.

Get daily National news

“When they went to the home and did the assessment, many factors started to come in,” she said.

The suspect turned out to be a teenager. He lived with an overwhelmed parent who wasn’t supervising his online use. Police weren’t going to charge him with terrorism, and didn’t believe he posed a realistic threat.

But they also didn’t want to turn their backs on a youth who was talking to ISIS, so they arrested him on a peace bond, referred him to an imam and he started seeing a psychologist.

“You can’t just walk away,” Supt. Crouch said. “You can’t just turn around and say, ‘Well, there’s nothing for us … because it still is going to be a problem somewhere.”

“And then you want to kind of help that before it escalates even more, so that we’re not then called back to deal with a situation,” she added. “So that’s the whole goal, to stop it before an incident happens.”

WATCH: Youth charged with terrorism following Kingston raids: RCMP

Police have struggled to do that in the past. Martin Rouleau-Couture, Aaron Driver and Abdulahi Sharif were all known to police for extremism, but were still allegedly able to plot attacks.

To improve on that record, more than 30 officers have been trained on the assessment tool used to determine the level of risk posed by a suspected extremist, and the RCMP has been talking to community groups, religious leaders and school resource officers, among others.

“If the community doesn’t know about the issues that we see through our lens, then how is it that we help educate them?” Crouch said. “So we started to engaged them to provide them the information that we see.”

Prevention programming is politically-charged, with the Conservatives accusing the government of sending terrorists to “poetry classes,” while Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has spoken about “de-programming people who want to harm our society.”

But terrorism prevention is a work in progress. There is no formal system in place for those who need help, and even the experts aren’t sure what works.

There are questions about who is qualified to counsel extremists, and there is little solid evidence on how best to guide someone away from radical violence.

In Toronto and several other Canadian cities, police refer cases to community hubs — roundtables of social services and health agencies. As with gangs and drugs, the hubs come up with a plan that tries to address the underlying problems that have made the person vulnerable to recruitment.

“By addressing a given individual’s range of needs, vulnerabilities and risks, multi-agency programs can potentially redirect them away from violent extremism before it occurs,” according to the government’s National Strategy on Countering Radicalization to Violence.

Prof. Joana Cook, an expert on countering violent extremism, said that approach was “largely recognized as the most suitable,” partly because the reasons people fall into extremism are so varied.

“That means that responses and interventions have to be able to identify and respond to a broad array of factors that may be present in each individual’s circumstances,” she said.

Interventions can be problematic because someone expressing radical views may not be a public safety threat, and there is no consensus about what turns extremists into violent extremists.

But she said there was value to early intervention, and families were more likely to seek help if cases were channelled to social services agencies rather than dealt with solely by police.

“No parent wants to turn their child in to the police,” said Cook, a senior research fellow at the International Centre for the Study of Radicalization and Political Violence.

“But if they may be able to access psychologists, counsellors, social workers or other relevant professionals, then there can be many positive benefits to all parties involved.”

Another unknown concerns the role of former extremists. The RCMP has been working with several, among them Brad Galloway, a former Canadian racist leader who quit, went to university and now helps research and combat extremism.

Galloway said when he left his neo-Nazi group, police in B.C. offered support. “They stayed involved,” he said in an interview. “I could have easily gotten tied back into it, but they definitely played a role in assisting.”

In retrospect, he believes the death of a friend made him vulnerable to recruitment into the racist far-right. He wants to help in Toronto with community education and interventions.

“We need to be responsible for this stuff because look what’s happening,” he said, speaking after the New Zealand mosque shootings and the attack days later in the Netherlands.

“We’ve got to be more involved in trying to prevent this stuff on the early end.”

WATCH: How RCMP plans to intervene with extremists

When Crouch joined INSET eight years ago “it was all about enforcement,” she said. But having worked in drugs and gangs, she was well-versed in prevention strategies and set out to apply them to counter-terrorism.

“Young people need kind of lines in the sand drawn for what’s good behaviour and what’s accepted,” she said.

“It’s national security. Of course, the impact is probably greater if something significant happens. But really, why people get involved in risky behaviour is fundamentally the same potential reasons why they get involved in drugs or gangs.”

While national security is traditionally secretive, the need to be more open to the community became apparent when Canadians began leaving for Syria and Iraq, she said.

“At the height of the high-risk travellers, when they were going over to Syria to solidify the caliphate over there, one of the gaps that we recognized was that the community itself was really quiet,” said Crouch.

“But that’s not necessarily their fault because I’m not sure they understood the extent of what was actually being done to recruit people,” she said.

WATCH: Aaron Driver’s father says son’s troubles started young

Prevention strategies also apply to the inmates coming out of prisons after serving time for terrorist offences, and those returning to Canada following stints with overseas terror groups.

The prospect of Canadians, many of them children, returning from ISIS, and uncertainty over whether there will be enough evidence to prosecute them, could put the fledgling prevention program to an important test.

Although “enforcement” is part of her unit’s name, Supt. Crouch said that with terrorism, Canadians expected more; they want police to stop attacks, not just investigate them later.

“Absolutely, we’re enforcement when you need to be,” she said. “But first and foremost, we’re about prevention.”

Stewart.Bell@globalnews.ca

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.