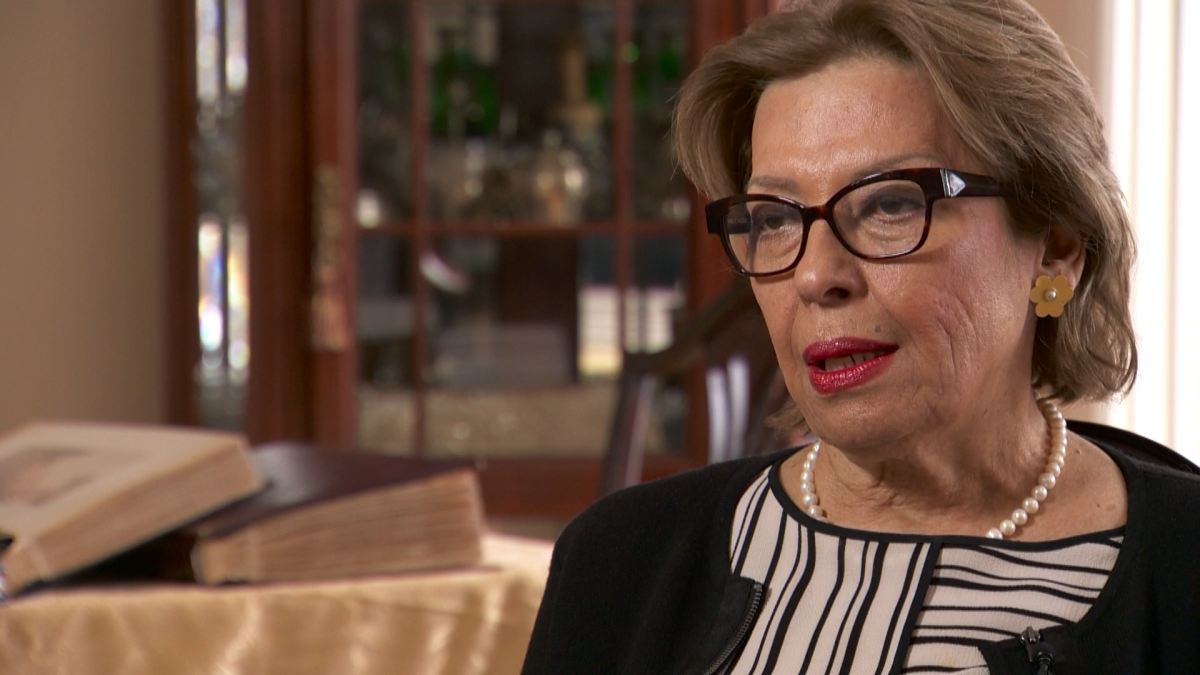

Zarrin Mohyeddin vividly remembers where she was exactly 40 years ago.

She was 27 years old and living in Tehran, the capital city of her native Iran. The country had endured months of mass protests against social injustice and corruption. And on February 11, 1979, Iran’s authoritarian regime and secular monarchy, under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, finally collapsed.

The revolution transformed Iran into an Islamic Republic.

But Mohyeddin wasn’t celebrating on the streets with many of her peers. Instead, she recalls, she was in her bedroom crying.

“It was a very sad time,” she said.

Mohyeddin was an activist from a progressive political family, who enjoyed a liberal western lifestyle — going to parties, driving and attending school alongside her male peers. She also chose not to wear a hijab.

“We were free,” she said. “We lived with the women who wore the hijab and they lived with us. We didn’t care that she is wearing a veil or scarf. And they didn’t care that we were in mini-skirt. At least they didn’t show it.”

But as the country’s monarchy collapsed, Mohyeddin worried that the revolution would backfire and that the Supreme Leader would reverse many existing freedoms and enforce a hard religious line. She was right.

“Everything was destroyed,” she said.

Get breaking National news

WATCH: Iran: A timeline from Persian monarchy to Islamic Republic

But Mohyeddin never had to endure Iran’s new Islamic Republic.

On May 4, 1979, she, her husband and their two young daughters fled to Canada, with help from her sister-in-law who’d emigrated a few years earlier.

“We came here and left everything (behind),” she said in an interview with Global News at her home in Thornhill, Ont. “I lost so much, but I’ve gained the most important thing: Freedom.”

Some of her extended family members who remained in Iran were later arrested. Her cousin’s husband, a military general under the Shah, was executed.

Forty years later, the country’s persecution of political opponents continues, according to Homa Hoodfar. The Iranian-Canadian professor of anthropology at Montreal’s Concordia University was arrested during a visit to Iran in 2016. They accused her of “dabbling in feminism,” after she’d published a book on the importance of gender quotas in parliamentary systems and another on women’s sports in Muslim countries.

“They kind’ve thought that I was promoting feminism in sport in Iran so that men and women can swim together and basically undermine Islamic culture. That was part of their argument,” she said.

For her alleged crime, the 65-year-old spent 112 days in Iran’s notorious Evin Prison.

“I was, most of the time, in a very small cell that was basically the size of a double bed,” she recalls. “They wanted to break me physically so that I would agree to whatever they want me to sign. That was not an easy situation.”

Bessma Momani, a Middle East expert at the University of Waterloo, says the regime’s iron grip on power and its enriching of the business class have enabled it to survive for four decades. But she also believes another revolution is imminent, pointing to the country’s economic crisis and its demographics. According to a 2013 study by the United Nations and the University of Tehran, a third of Iran’s population are aged between 15 and 29.

“After 40 years, this Islamic theocracy is not what most Iranians want to live under,” Momani says. “This is a regime in its very last days. I think there’s an enormous amount of frustration. And the hope now is that perhaps, through democratic channels, through civil society activism, eventually the old guards will be sidelined. And there will be a new Iran that is far more liberal and secular.”

And if that happens, Mohyeddin hopes to return for a visit.

“I’m sure that one day it will happen,” she says. “Right now people are struggling to continue their life there.”

Comments