PARIS – It’s a data leak involving tens of thousands of offshore bank accounts, naming dozens of prominent figures around the world. And new details are being released by the day — raising the prospect that accounts based on promises of secrecy and tax shelter could someday offer neither.

Among those named include a top campaign official in France, the ex-wife of pardoned oil trader Marc Rich, Azerbaijan’s ruling family, the daughter of Imelda Marcos and the late Baron Elie de Rothschild. The widespread use of offshore accounts among the wealthy is widely known — even Mitt Romney acknowledged stashing some of his millions in investments in the Cayman Islands. But this week’s leak, orchestrated by a Washington, D.C.-based group called the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, appeared to be the broadest in what has been a steady stream of information emerging about hidden money in recent years amid a wave of anger targeting the super-rich in an age of austerity.

The leak allegedly involved records from 10 tax havens, where the world’s wealthy have long stashed funds. It uncovered a shadow network of empty holding companies and names essentially rented out to fill out boards of non-existent corporations, including a British couple listed as active in more than 2,000 entities, according to The Guardian newspaper, which participated in the global undertaking.

The project started with the receipt of a hard drive by an Australian journalist, Gerard Ryle, who took the data with him when he joined the consortium, according to the project’s website. The group, a project of the Washington-based Center for Public Integrity, has said the hard drive arrived in the mail, but did not specify its possible source or how it was authenticated. The consortium did not immediately respond to an emailed request for comment.

Rudolf Elmer, who once ran the Caribbean operations of the Swiss bank Julius Baer and turned whistleblower after he was dismissed in 2002, told The Associated Press that he considers the data to be authentic.

“This comprehensive information is like a torch that will probably set off a wildfire and bring to light a lot more about secretive tax havens,” he said.

Get weekly money news

The secret bank accounts of the rich and powerful have recently come under a crush of whistle-blowing scrutiny.

France’s former budget minister, Jerome Cahuzac, was forced to resign last month after a French investigative website unrelated to the latest leak revealed that he held offshore accounts — a particularly damaging scandal because he was spearheading a campaign against tax evasion. In 2010, a Greek journalist published a list of about 2,000 people holding undeclared Swiss bank accounts, disclosures that triggered a firestorm of outrage as Greeks were forced to swallow brutal austerity measures.

In November, an HSBC insider leaked a list of more than 8,000 customers with accounts based in Britain’s tiny Jersey Island, drawing an immediate tax investigation from Britain’s revenue and customs service. Two years before that, a former HSBC employee stole account details for 24,000 clients. Germany, eager to learn about its own tax cheats, promptly offered to buy the information.

“This just shows what we all know, which is that for decades we have seen the emergence of globalization on the one hand and governments that were unable to co-ordinate and co-operate on the other hand,” Pascal Saint-Amans, head of tax policy for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, said Friday.

There is nothing inherently illegal about opening bank accounts overseas, but it’s well known that the wealthy use them to avoid higher taxes at home — a practice that Saint-Amans said was quickly falling afoul of governments desperate for revenue, especially those suffering in the European financial crisis.

Britain has an outsized share of offshore territories, which include the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands and the Channel Islands, whose 4 1/2 square miles (12 square kilometres) are saturated with current and former British company directors, according to The Guardian.

“Britain has this network of satellite tax havens around the world that have been acting as feeders,” said Nicholas Shaxon, author of the book “Treasure Islands.”

Shaxon said he was encouraged by the succession of whistleblowing employees over the years, and described the latest leak as the most significant to date.

“I hope this has created a new willingness among players who are inside the system to say, ‘Hang on, maybe this isn’t such a good thing.'” Shaxon said.

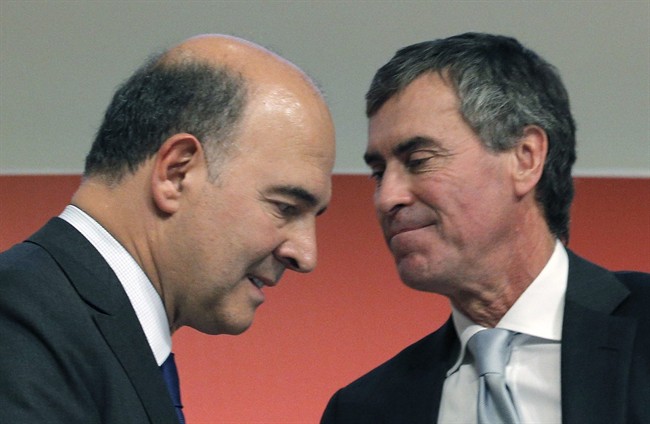

French President Francois Hollande, who has promised to clean up France’s finances, has had a particularly bad week when it comes to news about tax havens. No sooner had Cahuzac admitted lying about his offshore accounts than news emerged in the newspaper Le Monde that his former campaign treasurer, Jean-Jacque Augier, was a shareholder in two firms in the Cayman Islands, through a holding company.

Augier said he did nothing wrong. Cahuzac was felled by a recording of him talking about his accounts that was leaked to French website Mediapart.

The ICIJ consortium promised Friday to continue publishing details in coming week.

Tim Ridley, former chairman of the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority, warned against any satisfaction people may get from seeing the private banking information of the wealthy splashed across the Internet.

“Whatever may happen with offshore accounts today with everybody smiling about it could happen to onshore accounts in London or New York tomorrow,” Ridley said. “Normally people are entitled to information about their financial affairs or their medical affairs to be private.”

Ridley said there remained entirely legitimate reasons to set up accounts offshore, even for individuals, especially those from volatile countries: “Unstable governments have a habit of taking people’s money in unjustified circumstances.”

Shaxon was less concerned about the rights of wealthy individuals holding secret bank accounts.

“I don’t think we should be worried about the sensitivities of the poor banker and poor criminals whose criminal activities are being exposed,” he said. “If there are people who are doing nothing wrong and their information is being exposed, then it’s collateral. It’s a price to be paid.”

Both Ridley and Shaxon — coming from entirely opposite perspectives — agreed that the disclosures dented the world of offshore banking, but were hardly a fatal blow.

And experts say it will take years for current efforts against secrecy to fully take hold.

“It is ultimately public pressure that is going to make a difference here,” said Shaxon.

Comments