Two University of Calgary (U of C) researchers have uncovered what’s believed to be the first-ever British whaling wreckage in Canada’s High Arctic.

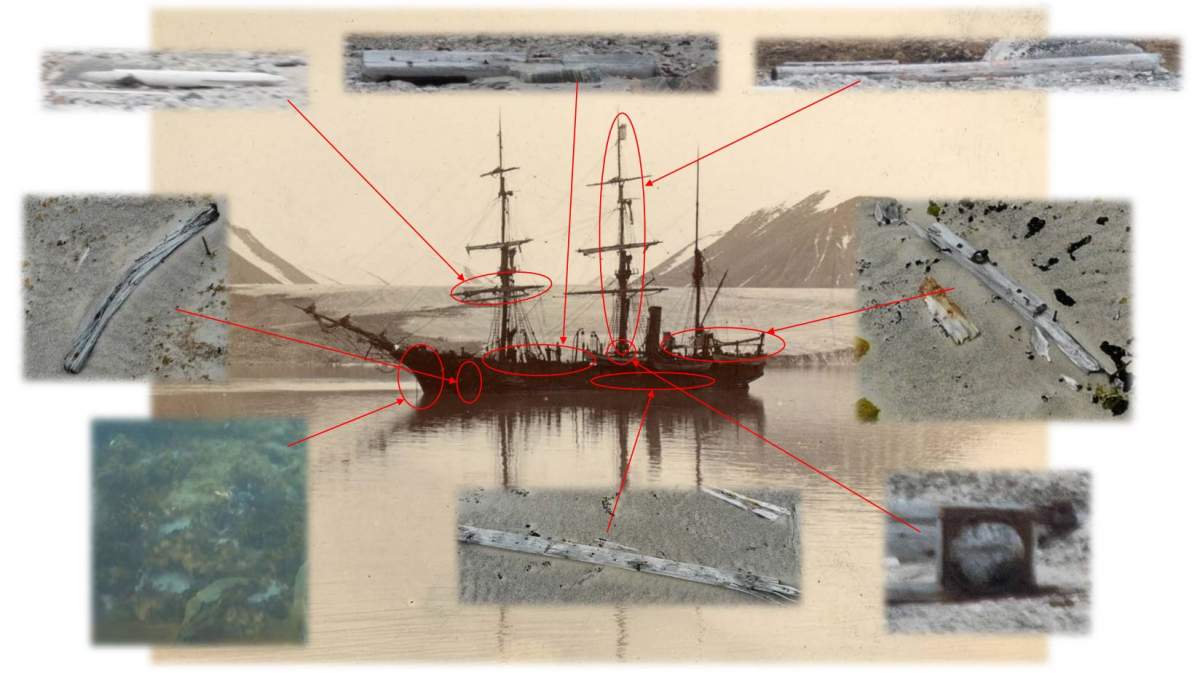

The remarkable new discovery dates back to more than a century ago – researchers believe the whaling ship Nova Zembla hit a reef off the coast of Baffin Bay and sank in the fjord in 1902.

Climate historian Matthew Ayre and underwater archaeologist Michael Moloney, partnering with the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, embarked on an ambitious expedition deep in the Arctic on Aug. 31, in search of the ruins.

The four-person crew, armed with a drone and sonar imaging from a remote-operated underwater vehicle (ROV), relied heavily on months of historical data to zero in on their search area. They were limited to a short seven-hour window.

“Sometimes finding things underwater is like looking for a needle in a haystack,” Moloney said.

“This is the biggest home-grown discovery I’ve ever made” he said.

With subzero temperatures, the crew’s scope was so vast and remote that there were no signs of civilization for kilometres – which according to Moloney, only reinforced their belief that the wreckage would still be there.

“We know we were in the right location. We know all the archival material led us to this spot… we don’t know of any other shipwreck within a couple hundred kilometres of this area,” Moloney said.

In the seventh, and final hour of their search, the men located wooden remains and other evidence of the shipwreck washed ashore on the beach, near Buchan Gulf on the east coast of the island.

Inland, wooden support beams and several mast rivets lay as clear as day – still intact more than a century later.

Get daily National news

The isolated and harsh conditions of the Arctic meant little could survive. The pair were almost certain their discovery was that of the Nova Zembla.

“I’d say we’re about 90 per cent sure… all of the timbers we found, all the materials, all of the construction techniques that were used are consistent with the age of the ship and the imaging we have of it,” Moloney said.

Once the crew found the ship pieces on the beach, they checked their historical records which led them to clues in the water.

“We went into the historical records and it says 300 metres off the beach, and we go 300 metres off the beach and almost instantaneously, we find an anchor,” Ayre said.

“We found it. It was a pretty tall order to say we were going to find it in seven hours.”

The pair were dropped off by a cruise ship passing through the area, and had set out in a small Zodiac in search of any signs of the whaling ship.

“You’re in the right place but sometimes you don’t see what’s there to see,” Moloney said.

The discovery provided a glimpse into the dangerous whaling industry long extinct and forgotten.

“This ship, there’s not a lot in the history books about the social aspect about life aboard these ships, and especially during this time period,” Moloney said.

The postdoctoral fellows said while it wasn’t unusual to find a shipwreck detailed in the log books, it was unusual to find the specific coordinates.

“There were over 200 shipwrecks in the whaling trade,” Ayre said.

Ayre said the discovery of the Nova Zembla will help researchers learn more about the whaling industry and how ships navigated the High Arctic more than 100 years ago. He believes it will also give insight into how whalers lived and survived the harsh conditions.

Ayre and Moloney plan to head back to the Arctic next year to do a more comprehensive search in hopes of recovering more artifacts.

The plan, with enough funding, is to gather and reclaim the wreckage to further examine it. They hope to stay for at least a week and ideally, do a full scale survey underwater and of the beach.

- Calgary family uses billboard in plea to find a kidney donor

- Tumbler Ridge school shooting victim set to hopefully return home soon from Vancouver hospital

- Alberta government announces purchase of new waterbombers to fight wildfires

- Edmonton police seek public help on investigation into fatal shooting

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.