Huong Dac Doan was 16 when he walked into a Vancouver restaurant with a handgun and attempted to rob it.

Three years later, he was convicted in another robbery, this time shooting one victim in the chest and another in the leg, according to documents from the B.C. Supreme Court.

Both lived but Doan was handed his first federal sentence — and a deportation order in 1997.

“Mr. Doan has extensive long-standing gang ties with Asian Organized Crime that are well documented throughout his file,” the Canada Border Services Agency said.

“It appears that he has connections with organized crime internationally and in other parts of Canada.”

More than 20 years later, he is still living in Canada.

Ordered Out But Still Here:

PART 1: Canada is failing to deport criminals. Here’s why it can take years, sometimes decades

PART 3: Canada struggles to deport foreign criminals. It’s even harder when they’re ‘stateless’ persons

The Canadian government considers Doan, 41, a stateless person. He was born Dec. 12, 1976, to parents fleeing the Vietnam War and ended up in a UN refugee camp in Hong Kong. His family landed in Halifax in 1991 before moving to B.C.

Doan is among hundreds of people caught up in Canada’s deportation system whom Canadian officials have deemed a criminal or security risk. And while government policy says removal orders must be enforced “as soon as possible,” the reality is some people can languish for years, sometimes in immigration detention, while they wait to find out if Canada will remove them or let them stay.

A Global News investigation has found the federal government has struggled to remove individuals under deportation orders for security, crimes against humanity, criminal convictions or ties to organized crime.

WATCH: Canada’s growing backlog of persons ordered deported for crime or security concerns

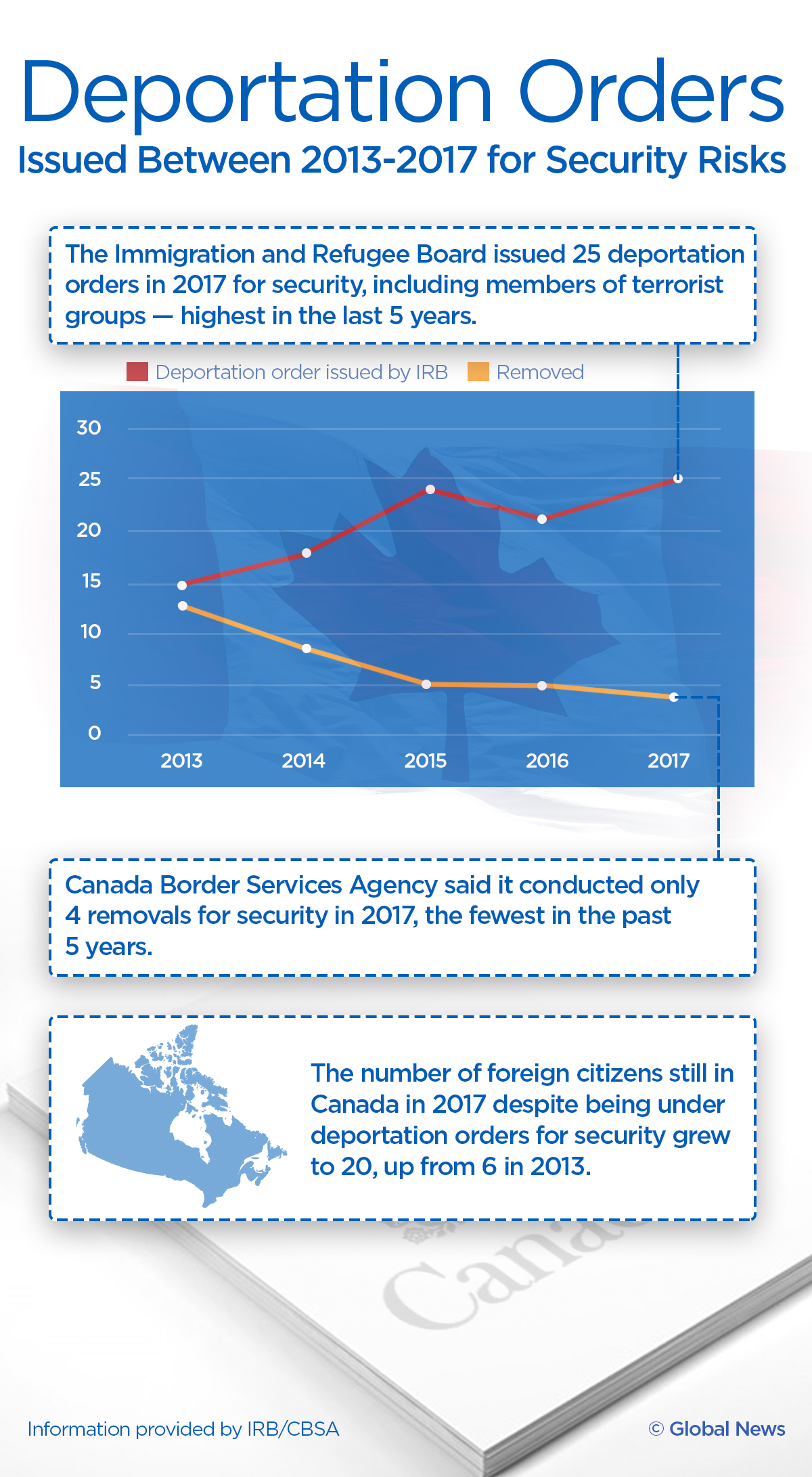

New statistics from the CBSA, obtained exclusively by Global News, show the number of foreign citizens living in Canada, despite being deemed a risk to public safety or security, skyrocketed to nearly 1,200 in 2017 from 291 in 2012. It also reveals that removals for these individuals, who are supposed to be the government’s top priorities, have declined by a third since 2014.

While CBSA officials face several delays when deporting criminals — foreign governments refusing to issue travel documents, drawn-out legal proceedings or officials losing track of a person — removing someone who is not recognized as a national by any state can be a major roadblock to a removal.

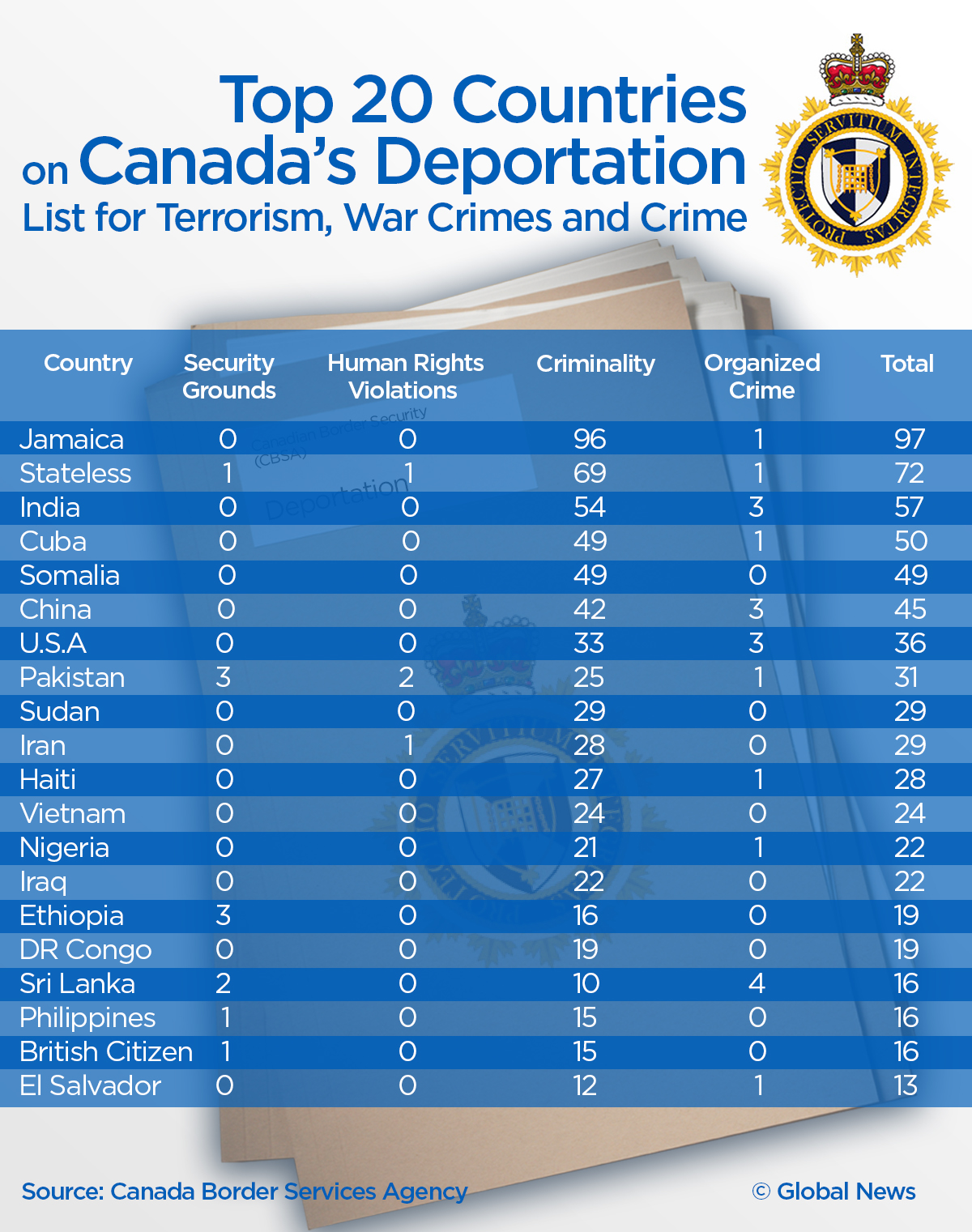

The data shows “stateless” individuals are near the top of the CBSA’s growing list of removals. The agency listed 72 people with no country of origin who have been ordered removed for security or criminal risk, but who are still here. Individuals with Jamaican citizenship are at the top of the list with 97, followed by India (57), Cuba (50) and Somalia (49).

There are currently 24 Vietnamese citizens under deportation orders for serious crimes still in Canada. In 17 of those cases, Vietnam’s government is refusing to issue travel documents.

Richard Kurland, an immigration lawyer based in Vancouver, called the growing backlog of “stateless” individuals a “serious” problem for Canadian officials.

“We can’t deport them to the country of physical origin,” Kurland said. “Possibly we can send them back to the country of citizenship, but the receiving country has to recognize the person as one of theirs. And if they don’t, we’re stuck again.”

The CBSA’s attempts to remove Doan have been hindered by the Vietnamese government which has — so far — refused to offer him citizenship papers.

“His application for a travel document was refused by the Vietnamese authorities in 2004. Without a travel document, Mr. Doan cannot be removed from Canada,” reads a ruling from the Supreme Court of British Columbia. Subsequent attempts to remove Doan also failed as Vietnam refused to take him.

Get daily National news

“We can confirm that Mr. Huong Dac Doan is currently under an enforceable removal order,” said a CBSA spokesperson.

WATCH: Goodale sidesteps question about Canada’s deportation backlog of criminals

Kelly Sundberg spent 15 years with the CBSA and is now an associate professor at Mount Royal University in Calgary. He previously worked on the Doan case and said it’s emblematic of the challenge Canadian officials face when trying to deport criminals who don’t have a clear country of origin.

“We have a real difficulty getting documentation from abroad to support the removal efforts. It’s an example of how an incredibly bureaucratic, overburdened system is resulting in someone who arguably should have been removed a while ago remains in our country,” Sundberg said.

Canadian Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale declined a request for an interview. Scott Bardsley, a spokesman for Goodale, said part of CBSA process to remove an individual considered “stateless” is to confirm the person’s identity.

“Once the identity and country of origin are determined, the agency may proceed with obtaining the necessary travel documents,” Bardsley said in an email. “CBSA has staff dedicated to enforcing removals, which are carried out once all legal avenues of recourse have been exhausted.

Canada’s history of refusing to name uncooperative countries is in stark contrast to the U.S., which publicly identifies and will sometimes sanction or withhold aid to countries that refuse to take back their citizens. The U.S. slapped visa sanctions on four countries — Cambodia, Eritrea, Guinea and Sierra Leone — that refuse to take back foreign nationals deemed convicted of crimes.

WATCH: Canada’s growing backlog of persons ordered deported for crime or security concerns

Experts who spoke with Global News say Canada should do the same.

“We have to squeeze and squeeze hard the interest of that receiving country, in order to get our way,” Kurland said. “It could be diplomatically, enhanced trade sanctions, or even the imposition of a visa requirement on that country, stricter standards, unless that country takes back known criminals that are waiting for removal right here in Canada.”

Sundberg also pointed to other countries like Australia, New Zealand, the U.K. and Germany who take a “fairly aggressive” stance with countries that don’t issue travel documents for people subject for removal.

“Why is our government not doing the same?” he said. “These documents are for people who pose a risk and a threat to Canadians. Some of these individuals are drawing on social services that would be better spent on Canadians.”

READ MORE: Canada giving refugee status to border-crossers at rising rates

In 2006, Doan “directed and participated in the beating and torture” of a suspected B.C. drug kingpin and his girlfriend, in an attempt to extort roughly $1.3 million, according to court documents.

Peter Li, his then-girlfriend Jennifer Pan, and his friend Xiao Cheng were kidnapped in Burnaby in February 2006 and held at a house in nearby Richmond, where they were beaten and tortured over a period of 25 days, according to court documents.

“Huong Doan then pulled his hair and beat him by slapping him very hard a few times in the face and on the back of his head.”

The three were eventually released when Li and his family paid as much as $1.3 million in ransom money in three payments at dropoffs in Vancouver, Toronto and China.

Although Doan was found not guilty of kidnapping, he was convicted of inducing the victims to pay under threat of violence and unlawful confinement and handed a nearly eight-year federal sentence.

Another attempt at removal

By 2014, the CBSA considered another attempt at removing Doan.

“CBSA’s relationship with the Vietnamese authorities, which apparently had been strained for several years, had improved so that obtaining travel documents was more likely,” according to court documents. “It has been noted extensively through Mr. Doan’s file that he does not wish to return to Vietnam and that he does not have any ties to his home country.”

Global News was unable to reach Doan for comment. He was released on Oct. 15, 2017, after completing his sentence, according to the Parole Board of Canada.

Like Doan, there are hundreds of cases that reveal the growing conflict over how to handle violent refugees who cannot be deported.

Jacob Damiany Lunyamila, 42, of Vancouver, arrived in Canada after jumping off a ship in 1994 without any documentation and claiming to be a citizen of Rwanda, according to federal court documents. He was granted refugee status in 1996.

Between 1999 and 2013, Lunyamila became well-known to Vancouver police with nearly 400 interactions, according to federal court document, resulting in 95 criminal convictions and 54 charges.

“His convictions include uttering threats, sexual assault against a community worker and numerous incidents of physical assaults, including unprovoked attacks on complete strangers,” according to federal court documents. “He broke into an ex-girlfriend’s home and punched her in the face; he was also found with an axe concealed on his person.”

READ MORE: Would-be refugees fleeing Donald Trump policy may not fare better in Canada

Despite his extensive criminal history attributed partly to alcohol and mental health issues, under the law he is free to walk the streets.

“If he were Canadian he would be free today to roam the streets as he has served his sentences. However, he is not Canadian. He came here as a refugee from Rwanda,” Justice Sean Harrington said in an earlier federal court decision on the case.

Lunyamila’s lawyer Robin Bajer did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Lunyamila was deemed inadmissible to Canada in July 2012. He was ordered deported but has refused 10 separate requests from CBSA officials to sign travel documentation and the agency has been unable to get a passport from the Rwandan government for him to re-enter Rwanda.

READ MORE: Canada deporting fewer people for terrorism, war crimes, crime

CBSA officials believe Lunyamila is from Rwanda, but are also investigating the possibility he is from Tanzania, a neighbouring country in east Africa.

Peter Edelmann, an immigration lawyer, said that often times people who arrive in Canada irregularly can pose a challenge for officials as they might not have a clear country of origin.

In some cases, Edelmann said, a country embroiled in civil war or a period of unrest may not have the infrastructure to issue travel documents or work with Canadian officials to help identify someone.

Costs for removals

Five decisions by the Immigration and Refugee Board have called for the release of Lunyamila, but each time a federal judge has overruled the decision on the grounds he is as a flight risk and a danger.

Costs for removals can vary greatly. A 2016 document obtained by Global News, shows that while a land removal to the U.S. costs less than $100, a high profile overseas removal that involves chartering a private plane and medical personnel and other security escorts can cost up to $500,000.

The estimated average cost for an unescorted removal is approximately $1,500, according to 2016 CBSA documents, while the estimated average cost for an escorted removal, two escort officers, is approximately $15,000.

READ MORE:Canada rejects hundreds of immigrants based on incomplete data

Lunyamila’s stay in prison has also been called “indefinite” and he has refused to cooperate with CBSA officials, providing “contradictory and nonsensical information” in response to questions about his connections.

“My. Lunyamila has been a substantial cause of the difficulties in removing him, by virtue of his steadfast refusal to cooperate with the minister’s removal efforts,” Chief Justice Paul S. Crampton wrote in an October 2016 decision. “That refusal already created a substantial burden on this country’s detention system, this court (no less than 13 different members of this court have had to address his situation this year alone) and the taxpayer.”

“The solution is to ‘think outside the box’ for a solution that would result in Mr. Lunyamila’s full cooperation with the Minister’s efforts to remove him to Canada.”

In his ruling, Crampton wrote that a balance must be struck between public safety and the concern of indefinite detention, before ruling “in favour of continued detention.”

A February 2018 ruling from the Federal Court of Appeal dismissed Lunyamila’s appeal for release because the court concluded it did not have jurisdiction to hear the appeal. He remains in immigration detention in B.C.

Sundberg said the issue of removals and border security is “incredibly complex” and that it will only become more challenging for future governments with increasing global travel and migration.

“It’s an incredibly complex issue that is growing, yet when we think of border security, it’s often the last or even unknown aspect that we consider,” he said. “Entry to Canada is not a right. It’s only a right for Canadian citizens, and in this day and age of global travel and increased volumes of people, we need to do a better job.”

Andrew.russell@globalnews.ca

Stewart.Bell@globalnews.ca

Comments