An Ontario publishing company is recalling a children’s educational workbook that critics say misinforms kids about injustices faced by First Nations when European settlers arrived in Canada.

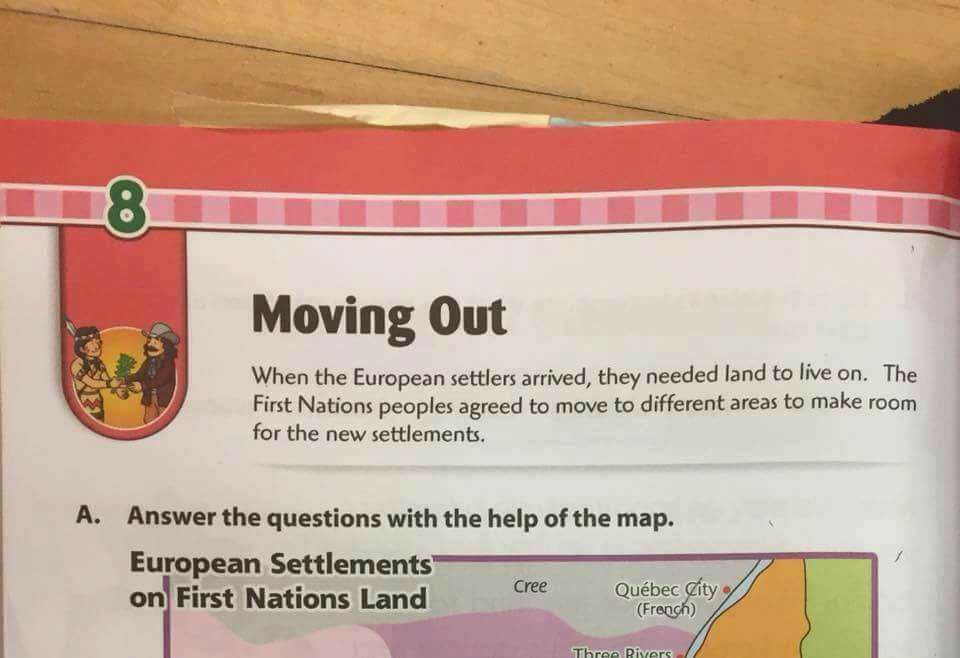

The book – “Complete Canadian Curriculum Grade 3” – has a section called Moving Out that says First Nations peoples agreed to move to different areas to make room for European settlers to move in.

Critics say the text glosses over the history of the country’s Indigenous population, pointing out that First Nations peoples were forced off their land.

The Popular Book Company Canada, based in Richmond Hill, Ont., had initially promised the book would be revised in later editions, but said in a statement issued Tuesday that it would be recalling the current edition immediately.

READ MORE: First Nations School of Toronto empowers students to become future leaders

“We know that our Complete Canadian Curriculum Grade 3 does not provide an accurate depiction of the interaction between Canada’s First Nations and European settlers,” it said. “While we cannot undo what has already been published, we are committed to making things better for future editions.”

The company, which said its aim has always been to publish quality workbooks, apologized to First Nations communities, customers, vendors and partners.

“We know that we have to do better and we know that it will take us some time to improve upon this experience,” it said, noting that it would be asking members of First Nations communities for help on how to best write about that part of Canadian history.

But some parents said the mistake shouldn’t have been made in the first place.

Get daily National news

Trish Frempong of Toronto said she was planning on purchasing the book for her seven-year-old daughter before she saw an image of the book’s contentious section on social media. She says she went to a nearby bookstore to check the book out for herself and decided against purchasing it.

She said the contentious section shouldn’t have been published, because it “perpetuates one particular narrative, that only serves one group of people, and it is anything but the truth.”

While some parents may find it difficult to talk to their kids about atrocities carried out against Indigenous peoples and other groups that have been marginalized, Frempong said that as a black woman, she has no choice but to educate her daughter.

READ MORE: Overhaul special education funding for First Nations students from reserves in Ontario

“We even talked about the history with Indigenous communities in Canada long before this book even was brought to my attention,” Frempong said. “She knows in a nutshell that Indigenous people didn’t give up their land freely, that they were harmed in the process, that violence was bestowed upon them and forced upon them and there’s a ripple effect.”

Jennifer Dockstader, executive director at the Fort Erie Native Friendship Centre, said the language used in the book – particularly a section that reportedly says Indigenous people would want to get away from settlers’ “hustle and bustle” – perpetuates negative stereotypes about First Nations peoples.

It suggests Indigenous people are simple-minded, that they didn’t have robust societies with hustle and bustle of their own, and that they wanted to be isolated – none of which is true, Dockstader said.

It’s dangerous to pass these stereotypes along to children, Dockstader said.

“If it’s taught to the non-Indigenous community, then they think that we actually wanted to be on reserves – reserves which are desolate and uncared for – so it’s our fault,” she said. “And then you tell our children these same things, and they’re like, ‘Well, I guess if that’s what my grandparents, great-grandparents wanted, I guess that’s okay, then.’ And so you see, the narrative is extremely dangerous.”

But Ian Sullivan, whose son is in the fourth grade and used the workbook last year, said he had no problem with the material.

Sullivan, who said his mother was Indigenous and his father was Irish, said when he was young, he was taught Indigenous history in stages. The violence inflicted upon First Nations peoples wasn’t taught until he was older, and that’s how he intends to teach his kids, he said

“When they start getting to later ages, that’s when they start to learn the more in-depth history of our people,” he said.

But Dockstader disagreed.

“It’s important that we be honest with our children from the first,” she said. “There is an opportunity to recognize that Indigenous people have knowledge that is of value.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.