Richmond City Centre and the Downtown Eastside (DTES).

On the surface, the two areas could not be more different.

One is a Vancouver suburb with rapid transit, pricey housing and condos for expensive cars. The other has poverty levels so high that it’s been cited, controversially, as “Canada’s poorest postal code.”

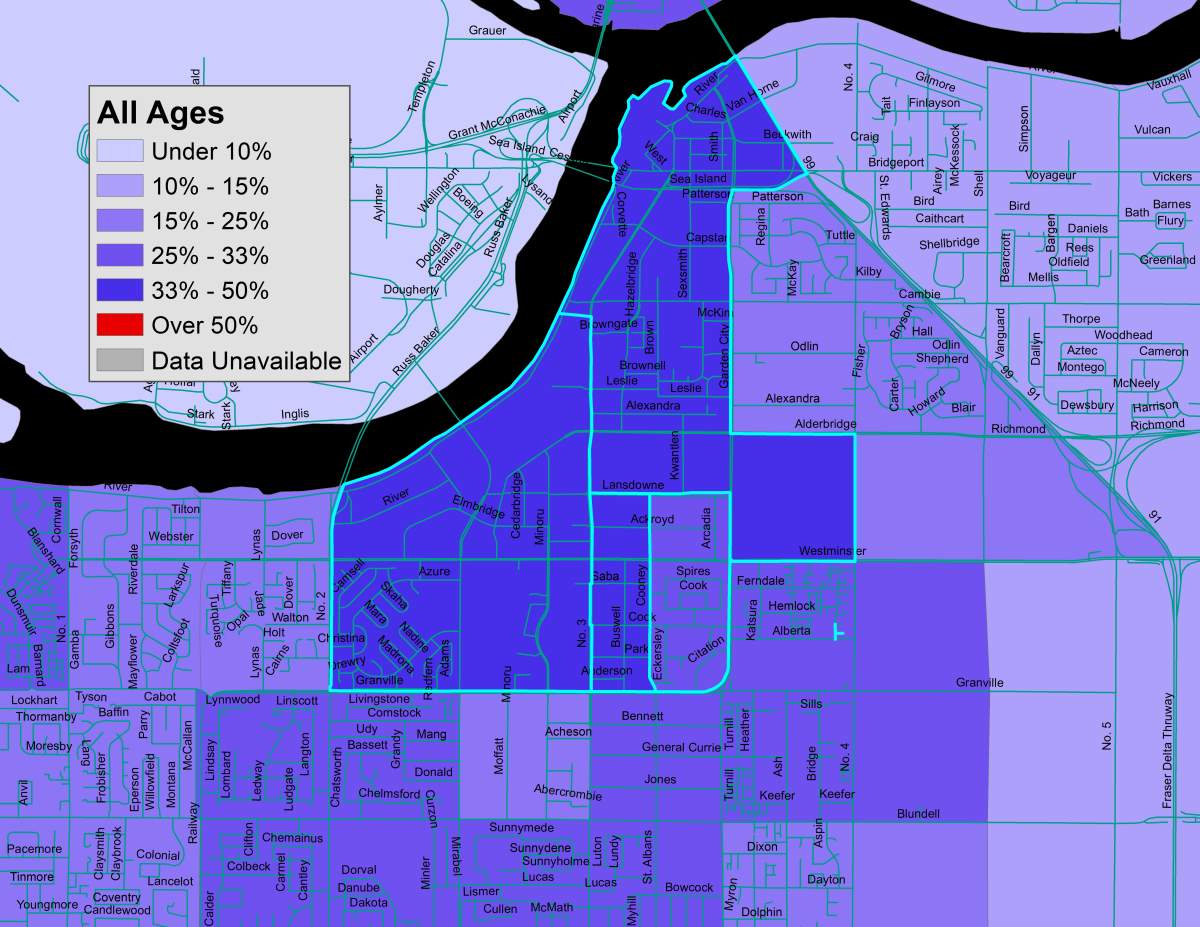

Yet similarities emerge when you look at the share of low-income people who live in these communities.

WATCH: Million dollar homes purchased by low-income buyers causing controversy

Andy Yan, the director of SFU’s City Program, found those similarities when he compared the low-income populations in these areas using Census data.

He found that 35.5 per cent of Richmond City Centre’s working-age population (18- to 64-year-olds) was in a low-income household, only five per cent lower than what he found in the DTES.

Yan calculated this by taking the five Census tracts that cover the Downtown Eastside and contrasting them against the five Census tracts that cover Richmond City Centre, an area largely seen as downtown Richmond, using incomes from 2015.

The finding stood out to Yan largely because they showed a low-income, working-age population comparable to the DTES in a city where the benchmark price of a home ran to over $700,000 at that time.

READ MORE: From 2001 to 2016, over 12,000 more Vancouver homes were left ’empty’: city report

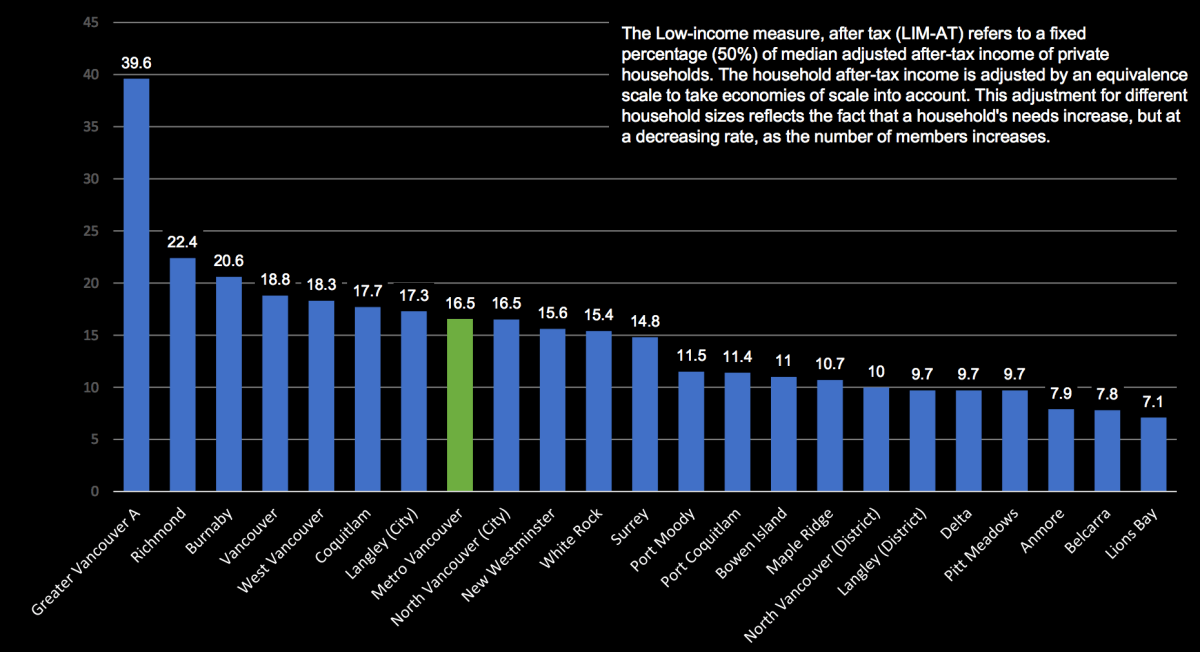

But that was just one component of a broader study called “Low Income Populations in Metro Vancouver,” which showed that Richmond had the highest share of individuals living in low-income households of any Metro Vancouver municipality in 2015.

Richmond’s share of individuals living in low-income households was 22.4 per cent, followed by Burnaby (20.6 per cent), the City of Vancouver (18.8 per cent), West Vancouver (18.3 per cent) and Coquitlam (17.7 per cent).

In order for a household to be considered low-income in 2015, it needed to have after-tax income below a certain threshold, depending on how many people lived in it.

Get daily National news

For a household of one person, that income threshold was $22,133. For a household of four people, it was $44,266.

Yan said the results in Richmond reflected the “suburbanization of poverty” in Metro Vancouver.

“Low-income households are increasingly being pushed into the suburbs, and this is arguably part of the trend in Canada and the U.S.,” he told Global News.

Yan said the housing crunch happening in cities like Vancouver is likely pushing low-income families into outlying communities such as Richmond, Burnaby and Coquitlam. But there are other factors driving them to these areas, too.

“I think some of these low-income households are locating in the area because of easy access to transit,” he said.

However, Yan also found it curious that a community like Richmond could have a relatively large share of low-income people, and yet also sustain high housing prices.

He said it’s possible that people are buying homes and then renting them out to low-income residents at lower rates.

READ MORE: Report recommends Canada revive wealthy immigrant program linked to soaring home prices

Daniel Hiebert, a UBC professor who has focused on the effects of immigration on Canada’s housing markets, thinks it’s unlikely that Richmond is seeing high levels of low-income residents because they’re all poor.

He thinks the relationship between high housing prices and low-income could have more to do with undeclared wealth.

WATCH: Quebec’s Immigrant Investor Program criticized for housing prices

Hiebert noted that Richmond has an outsized share of people who have come to Metro Vancouver through programs like the federal Immigrant Investor Program (IIP) or the Quebec Immigrant Investor Program (QIIP).

The federal program no longer exists, but the QIIP still allows immigrants with net worth of at least $1.6 million to make an $800,000 loan to the provincial government in exchange for Canadian permanent residency. They can settle anywhere in the country.

These programs were designed to stir economic activity. But experts say they largely haven’t succeeded, and have seen a number of participants who likely haven’t declared their total income.

“We have had a lot of investor immigrants come to Metro Vancouver and Richmond has a disproportionate share of them,” Hiebert told Global News.

“Few have established successful businesses in Canada so they mainly rely on wealth or income generated overseas. But they purchase houses.”

The high share of low-income people in a community with high housing prices suggests that Canada is “not tracking an essential component of economic well-being: wealth,” Hiebert said.

“It also may mean that there is more undeclared income in Richmond than elsewhere,” he added.

But there are limitations to this thesis: “The problem with undeclared income is that it’s by definition impossible to measure. So this bit can’t be proven.”

READ MORE: This 1989 documentary on Asian investment in Vancouver shows how little has changed

Joshua Gordon, an SFU professor who focuses on housing affordability, said the situation in Richmond “largely reflects the sordid history of the investor immigration program.”

“The program effectively sold citizenship to wealthy individuals abroad, but did not enforce any participation in the local economy in subsequent years,” he told Global News.

“This incentivized free-riding behaviour, where wealthy individuals could conceal their global income and avoid paying their fair share of taxes, and predictably that’s what we see.”

Gordon said the trend in Richmond provides further evidence that Canada needs to restructure its tax system to make it difficult for wealthy people to “dodge their fair share of taxes.”

In Metro Vancouver, he said this could be done by implementing a property surtax that would be offset by income taxes paid, “with exemptions for most seniors.”

Because under the current situation, “There is a lot of government revenue that is being left on the table,” Gordon said.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.