The North Korean regime has a line in wild rhetoric — in July, for example, it threatened to turn South Korea’s capital, Seoul, into a “lake of fire,” and this week, it threatened the United States with a “severe lesson” if it tried to take military action against its nuclear arsenal.

On Tuesday, U.S. President Donald Trump seemed to be taking his tone from Pyongyang when he said he would respond to threats from North Korea (which have gone on for years) with “fire and fury like the world has never seen.”

Should it be taken seriously, literally, seriously but not literally, or both seriously and literally?

In the region, the worry is that the fire may not be metaphorical. A report Tuesday said that the North had managed to put a nuclear weapon on a missile, a prospect that alarms Japan, which is well within range. (North Korea is thought to have dozens of nuclear warheads.) On Wednesday, the North Koreans said they were studying a plan for a missile strike on the U.S. base on the Pacific island of Guam, an American territory.

READ: Trump pledges ‘fire and fury,’ in words not unlike those of North Korea

Canada hasn’t been immune from conflict in Korea in the past.

Canadian troops fought in Korea between 1951, the year after North Korea invaded the south, and 1953, when the war ended in an ambiguous truce. 516 Canadians died in the conflict, more than three times the number killed more recently in Afghanistan.

READ: Korea: Mapping the dead of Canada’s forgotten war

Could we be entangled in a war on the peninsula again?

A U.S. pre-emptive strike

Trying to destroy North Korea’s nuclear stockpile with a surprise attack is a tempting but risky strategy. Due to the speed and secrecy involved, it’s unlikely to involve Canada, at least at first.

“A pre-emptive strike would happen lightning-quick,” Carleton University international relations expert Alex Wilner explains.

Get breaking National news

“It would be massive. The Americans, in this case, would not want the North Koreans to be able to retaliate against South Korea. We might not even have an opportunity to know.”

“The Americans would want to do this as deliberately as they can; they won’t want to bog it down in coalition politics.”

This is an extremely high-stakes strategy, too dangerous for past U.S. administrations to approve — if only part of the North’s nuclear arsenal is destroyed, the surviving weapons are quite likely to be used. The question is whether Trump is far enough outside the Washington consensus about dealing with North Korea to consider it.

“I think he is quite different, so maybe he is willing to do something dramatic like that. But the risks are quite high.”

A successful first strike, and the downfall of the North Korean regime, would raise new problems that Canadians would inevitably have to help deal with.

“It’s possible that the whole society collapses, and there’s just mayhem on the streets. That would be a complicated scenario for Canadians to be involved with too, because it leads quickly to a humanitarian crisis.”

Trying to occupy a country that has been cut off from the outside world for decades, starved and brainwashed, would create extreme challenges, he warns.

“It’s possible some North Koreans will continue to fight on even though the state itself has collapsed.”

The Chinese may simply take over in the end.

“We may not have a say in the matter.”

“It’s possible the Chinese could see this as their version of Haiti. It’s in their hemisphere, it’s in their immediate backyard, they know a lot of the players.”

A North Korean attack on South Korea

This could take various forms — the 2018 Winter Olympics, which will be hosted by South Korea, is an obvious target. A 1950-style invasion is only one of a number of possibilities.

READ: IOC ‘very closely’ monitoring situation on Korean peninsula as 2018 Winter Olympics approach

Canada doesn’t have a NATO-style defence agreement with South Korea (the Americans do), but we might be drawn in, in any case.

“We might want to help the South Koreans, of course, but I don’t think we’re obligated to do so.”

“You can think of the Australians pitching in – if they do that, then maybe we have to do something. That’s how you end up with some form of Canadian participation in a Korean conflict.”

A North Korean missile attack on Guam

It’s not clear whether an attack on Guam, which is a U.S. territory and not a state, would trigger Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty and force Canada to go to war with North Korea.

“Are NATO allies required to go to war in defence of the United States because of an attack on Guam?” Wilner asks. “It would be like an attack on a French dominion in Africa — that probably wouldn’t trigger Article 5.”

READ: North Korea considers plan to attack U.S. territory Guam

A serious cyberattack

A large-scale, successful electronic attack on a First World country, aimed at disrupting infrastructure — utilities, food distribution systems, banking — would be a new thing in warfare.

It wouldn’t, on some level, be that much of a surprise, though. In 2014, North Korea hacked Sony Pictures over a movie it objected to. And Russia has been blamed for hacking attacks on Ukraine’s electrical grid.

“We know that the North Koreans are building cyber capabilities, so maybe there’s a scenario where they really do have some kind of doomsday cyber weapon that they unleash before or after a more traditional military engagement,” Wilner says.

The first step would be to lay blame, and the next would be to figure out how to retaliate — electronically, physically or both. Canada could have a role in both stages.

“The first thing is to understand who did it. Who gave the order, who did the training. Canada is a prominent player in that, because we do have quite sophisticated cyber and signals intelligence capabilities.”

“Once we have attribution, it requires Canada, in partnership with the Americans and others, to decide what to do next. Do we retaliate only in cyberspace, or do we retaliate across domains?”

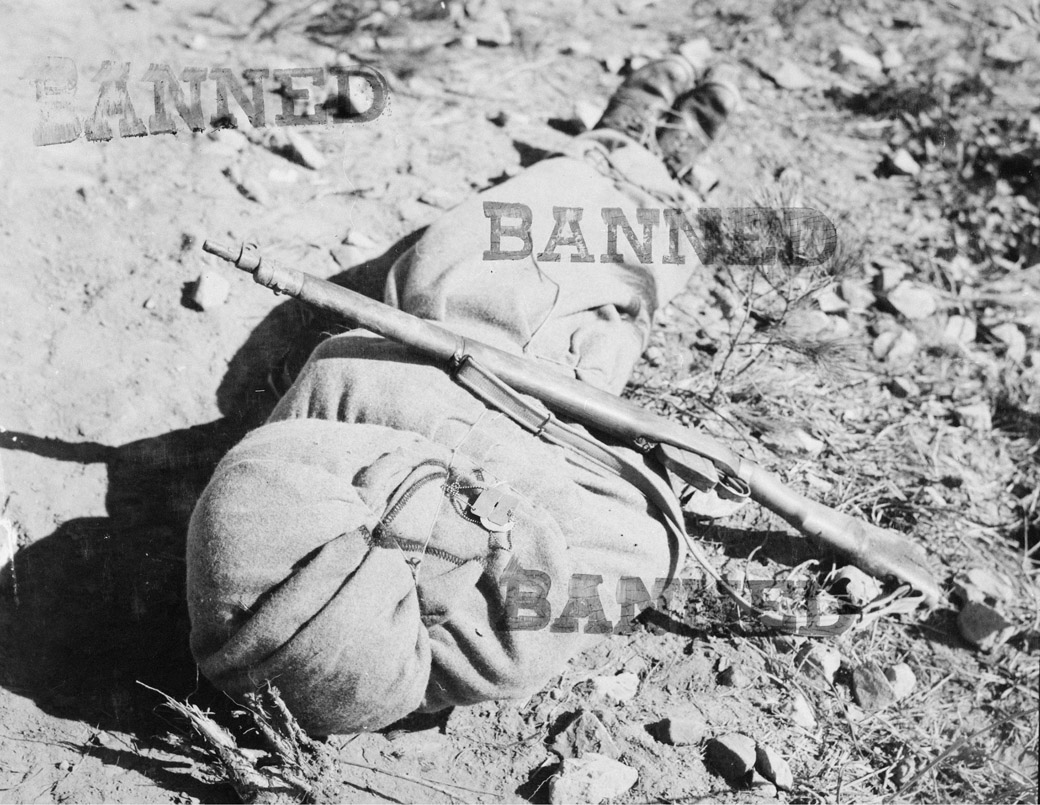

Gallery: Images of Canadian soldiers in Korea burying and remembering their dead

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.