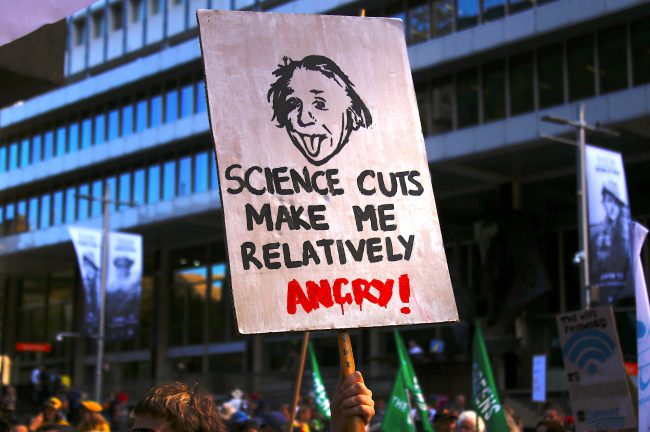

“What do we want? Evidence-based decision-making. When do we want it? After peer review!” read one of the many signs held at Ottawa’s March for Science rally on Saturday.

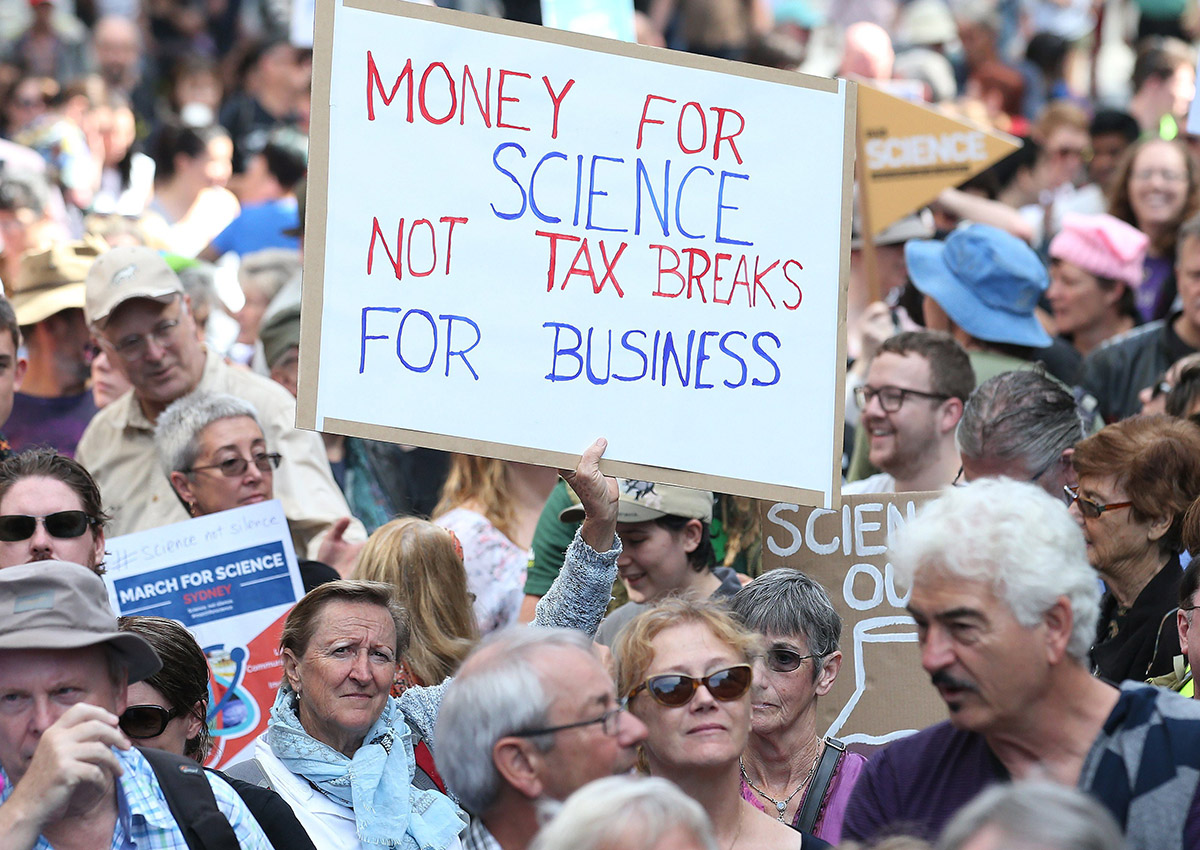

On Saturday, to mark Earth Day, people in almost 500 cities across multiple continents marched in solidarity for the promotion of science. What began as a single rally in Washington, D.C., to protest the attitude against the sciences demonstrated by the current U.S. government grew into an international political statement that included over a dozen Canadian cities.

Many who followed the marches on social media may not have known that Canada has a unique connection to these rallies, as a similar scenario occurred here at home just five years ago. Science advocacy grew in Canada after scientists began to chafe at limitations on researchers and believed those restrictions and funding cuts for key programs needed to be addressed.

2006: Federal government’s new communications policy

It began in the early 2000s, with a set of procedures introduced in 2006 around how government scientists were allowed to speak about their research in the media. Before these rules were adopted, journalists were for the most part able to contact scientists directly for interviews. After 2006, however, scientists were required to get approval from their departmental minister’s office before speaking to media. Katie Gibbs, an Ottawa scientist who would go on to organize marches on Parliament to address the issue in 2012, discussed her concerns with this policy.

“Under the Harper government, they really changed the policies about how scientists could communicate their results to the public,” she says. Gibbs added that government scientists were unable to take direct calls from media, or make unapproved public presentations. This policy, however, was applied at large to several governmental departments beyond just scientists.

According to Evan Savage, a software developer and organizer for Toronto’s March on Science, this policy goes beyond scientists’ inability to speak freely about their work to journalists. “The public has a right to know what research is being funded with their tax dollars,” Savage points out.

WATCH: International petition urges Harper to stop muzzling scientists

2010: Bill C-626, elimination of the mandatory long-form census

As time went on, subtle actions were taken. When the long-form census was eliminated in 2011, many were confused by the decision. Gibbs describes this as an example of the cuts made to evidence-based decision-making made under Stephen Harper’s government. The purpose of the census was to gather data that allowed governments to plan certain programs.

Researchers also used census data to compare income trends among immigrants and visible minorities, finding gaps between newcomers and second-generation Canadians, men and women, etc. The data was also used when planning public health, public transit, rural development, and other kinds of economic planning.

“The census was a big campaign for us, and talking about what was lost in reliable data,” explains Dan Weaver, a Toronto-based scientist who’s heavily involved with science advocacy in Canada. Weaver would go on to organize several protests in 2013 as part of this movement.

For the mandatory census, which is distributed every five years, most Canadian households would receive an eight-question survey. A longer, 61-question survey was distributed to a fifth of households across the country. That survey was replaced with the voluntary “National Household Survey” in 2011, which garnered a poor response rate in some geographic areas. Some point out it’s important to note that this move came in response to some Canadians expressing resentment to the personal questions on the longer survey.

Get breaking National news

WATCH: Long-form census makes its comeback

2012: Bill C-38, the Jobs, Growth and Long-term Prosperity Act

While the elimination of the census caused confusion, Bill C-38 launched an uproar. The 2012 budget bill from the Harper administration weakened the laws protecting the natural environment in Canada, and according to the Toronto Star, exempted projects from environmental assessment, limited the time permitted for public experts to weigh in on environmentally risky projects and removed protection for the Fisheries Act.

Five years ago on Earth Day, 250,000 people took to the streets in Montreal to demand that the government live up to the requirements of the Kyoto Protocol, signed in 1992. However, with the passing of Bill C-38, Canada officially withdrew from Kyoto.

At the time this bill was introduced, the Toronto Star reported that 74 per cent of Canadians wanted the government to take action on climate change, regardless of whether it led to higher energy prices. The Canadian Environmental Assessment also changed because of Bill C-38, along with the closure of the Experimental Lakes Area (ELA), the Polar Environmental Atmospheric Research Lab, and other cuts.

WATCH: Harper said economy trumps environmental concerns

2012-2013: Protesting the death of evidence

In July 2012, Gibbs was part of a small group of scientists that held the Death of Evidence marches on Parliament Hill. A handful of professors and graduate students at the University of Ottawa staged a mock funeral, which satirically mourned the “Death of Evidence.” Gibbs says that between 3,000 and 5,000 people showed up to the Death of Evidence rallies that year, a number that would continue to grow as the protests became more regular.

“We are here today to commemorate the untimely death of evidence in Canada,” Gibbs, then a doctoral student at the university, said at the event. A procession of over 200 scientists were led by pallbearers carrying a coffin through the streets of downtown Ottawa, en route to Parliament Hill. Eulogies for “evidence” were delivered.

At the time, Conservative MP Michelle Rempel countered that the government had actually increased funding for basic and applied research. The service closed with several scientists placing books into the coffin, including Darwin’s The Origin of Species. The Death of Evidence marches eventually led to a larger protest the following year organized by Dan Weaver, dubbed Stand Up for Science.

- Storm may bring flash flooding to Ontario, Quebec bracing for freezing rain

- Defence to call more witnesses in Frank Stronach’s sexual assault trial

- Saskatchewan minister says he’ll have meeting at library after reports of violence

- Fire underneath Saskatoon’s University Bridge causes damage to sewer line

Later in 2013, the organizers of these protests came together to form Evidence for Democracy, a non-partisan group that promotes evidence-based decision-making by Canadian regulators.

WATCH: U.S. scientists rally in Washington to protest Trump policies on Earth Day

2015: Justin Trudeau campaigns with scientific freedom as a campaign promise — and wins

According to Gibbs, Weaver and Savage, the 2015 election was the first time in Canadian history in which science became a campaign promise. Trudeau pledged throughout the 78-day campaign that government scientists would be allowed to speak freely about their work, that scientific analyses would be considered in government decisions, and that the role of Chief Science Officer would be created (for which the Liberals are currently hiring).

However, Weaver makes it clear that these promises were made in response to science advocacy across Canada, including the protests in recent years.

“Looking back at the 2015 election… it was an issue that people talked about,” Weaver says. “There was this enormous pressure that came out of the Evidence for Democracy movements and the Death of Evidence marches. That eventually reaches our leaders. They do respond if enough people raise their voices.”

Gibb does note that while new policy for government scientists has been drawn up by the Liberal government, the collective agreements have not yet been signed.

WATCH: Respect the science: Trudeau defends additional Trans Mountain pipeline review

2017: March for Science

This brings us to Earth Day 2017, when the largest science demonstration in history took place in 500 cities around the world. What began with a handful of scientists in Washington, D.C., quickly spread to science advocacy groups in other countries, and to 18 cities in Canada. The satellite event in Ottawa was organized by the same group of scientists and activists that marched on Parliament Hill five years ago — but for many of those in attendance, the event felt like déjà vu.

“In Canada in particular, we’ve seen a lot of these things before. There’s a massive understanding from people who have been doing this for a long time here in Canada that while things are getting better, we haven’t gone far enough,” explains Savage.

Under Trump, the U.S. government has moved to remove all mentions of climate change from the federal website, promised to eliminate the Climate Action Plan, and staff from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and other government employees have been told not to speak to the public. While some of these actions have been walked back or shut down, these announcements were made less than a month into the new administration.

While the purpose of the science marches, and the original intent of Evidence for Democracy, was to promote non-partisan support for the sciences, it’s become clear that science advocacy has become a growing political movement. While the impact of this trend on Canada remains uncertain, Canadian scientists’ dedication to ensuring science stays in the spotlight remains ongoing.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.