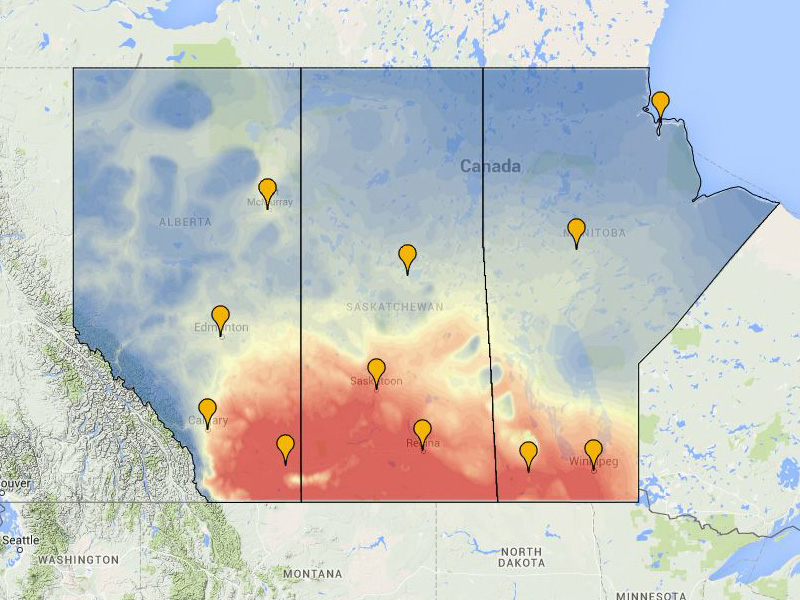

In May, climate researchers at the University of Winnipeg published a detailed, sobering map of how a warming climate will affect the Prairies.

All over the region, they predict, the number of days over 30 degrees will increase relentlessly.

Winnipeg, for example, now gets about 11 over-30 days a year, while Medicine Hat, Alta., gets 26. By the middle of the century, they predict, Winnipeg will see 46 over-30 days, while Medicine Hat will see 63.

(That means Medicine Hat would have the climate of modern-day Amarillo, Texas.)

“What we are trying to do is show people that this is a really vulnerable area, one of the very vulnerable areas of the world,” explains Danny Blair, a geography professor at the University of Winnipeg.

The temperature estimates assume nothing is done to curb global warming, but, Blair says, that’s the situation as it stands now.

“We’re trending toward the worst-case scenario now – let’s hope that doesn’t happen.”

READ MORE: Statue of Liberty, Easter Island among World Heritage sites threatened by climate change: UNESCO

The whole region is headed for hotter, drier summers, Blair says. That means major, complex changes for forests, agriculture (for good and ill) and for how we see and use water.

What’s ahead?

1) Bigger and fiercer forest fires

“Summers will not only get really warm, but on average drier than they are now,” Blair says. “Every once in a while it will be really hot and really dry. It’s the extremes that are really problematic, and the implications for forest fires are really quite worrisome. We’ve already seen an increase in the frequency and intensity of forest fires, and the modelling that we present here clearly indicates that this will only get worse if we let it get that far.”

Big, frequent forest fires are not only destructive in the north, they cause smoke and respiratory problems for people further south, he says.

While the forest fires raging in Fort McMurray, Alberta, can’t be blamed on climate change, it does give us a glimpse into what the future could look like.

Get daily National news

2) Farming in dry, hot areas will get harder. Maybe impossible

In the 1920s and 1930s, once-prosperous farms in Saskatchewan were devastated as the soil simply blew away – the Dust Bowl phenomenon. Blair and Dalhousie University-based food scientist Sylvain Charlebois say that isn’t likely to happen again in the same way.

“The Dust Bowl was really about not knowing much about soil science and plant science,” Charlebois explains.

READ MORE: As climate warms, grizzly bears and polar bears interbreed

However, farming in the Palliser Triangle, the naturally arid area stretching from the Rockies through southern Alberta and partway into Saskatchewan, may be very challenging, Blair says:

“Southern Alberta and southwestern Saskatchewan will become a landscape that will not be conducive to viable agriculture. Certainly there are going to be years where there is going to be sufficient precipitation, but if the farm community is faced with drought crop failure three out of every five years, that’s not going to work.”

“The financial burden, the psychological burden on those communities will just not be sustainable in those kinds of conditions.”

3) Communities that depend on winter roads are in trouble

Many remote northern communities are supplied by seasonal roads that depend on deep, intense cold to support vehicles. As temperatures rise, their viable season will shrink or disappear.

“The winter road system is just not sustainable,” Blair warns. “We’re losing them rapidly. It’s expensive to build permanent roads to these remote communities. Winter roads are one of the prime examples of climate change now, and even more so in the future.”

READ MORE: Our climate change coverage

4) Farming in cool areas will get easier.

Nothing as complicated as climate change is all good or all bad. Blair and Charlebois agree that warming temperatures may open doors to new crops grown in new areas. Northern areas with good soil but short growing seasons may see much more agriculture.

But will there be enough water? That’s the catch.

“That growing season is going to expand, and that creates an opportunity, as long as water is available, for crops to be planted earlier and longer-maturing kinds of crops to be grown,” Blair says. “The Grande Prairie (Alta.) region is going to see some benefits, in terms of the lengthening of the growing season, as long as there’s water available,” Blair says.

“Climate change is certainly a threat, but it could also be an opportunity, as long as there is water around, and that is really the key factor here,” Charlebois says.

5) Warming means a shrinking snow pack in the Rockies. That’s bad news for oil sands production

Oil sands production in northern Alberta uses a lot of fresh water. The Athabaska River, where the water is taken from, is fed from snow pack high in the Rocky Mountains. Less snow pack means less river.

“The ice packs in the mountains are in fast retreat, and they are doomed, absolutely doomed in the future, almost no matter which way we go,” Blair says.

“That annual stream flow coming down from the melting glaciers in the springtime and early summer – that’s going to disappear. The oil sands use an enormous amount of water, much of which comes off the melting snow pack. And if the water supply is shrinking in the future, we’re going to have some fights over water.”

6) A shift away from water-loving crops

“We can look at crop diversity – lentils and pulses don’t require as much moisture,” Charlebois says. “There is worldwide demand for pulses in general.”

The climate maybe too dry and hot to support corn, Blair says, while Charlebois urges a rapid expansion of irrigation systems to support thirsty canola crops.

7) Conflict over water

When the water hole goes dry, a wise person once said, the animals look at each other differently.

“We take water a little bit for granted right now,” Blair says.

But if there isn’t enough water for everything that everybody wants to do – power generation, municipal use, farming, oil production – there will be winners and losers, and ugly fights over which is which.

“Conflicts over water are going to be more problematic,” Blair warns. “If we let it go that far, there are undoubtedly going to be some conflicts.”

Comments