EDMONTON – If birds of a feather flock together, what were these beasts doing?

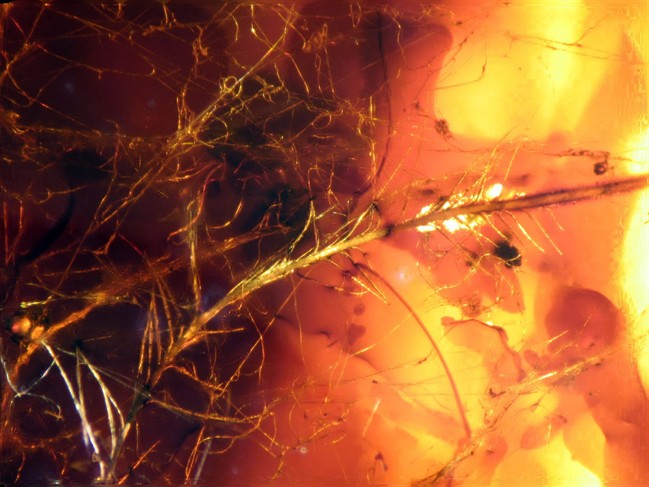

An ancient deposit of amber from southern Alberta has revealed that birds with feathers not that different from their modern descendants shared habitat with dinosaurs still sporting the most primitive of plumages.

“We’ve got two ends of the evolutionary-developmental model co-occurring, which is kind of weird,” said University of Alberta paleontologist Ryan McKellar, co-author of a paper on the Medicine Hat amber deposit in the journal Science.

“We’ve got what appear to be dinosaurs running around with some sort of plumage. And alongside these guys we’re also seeing feathers from what appear to be birds, some with very advanced shapes.”

Researchers found the 11 samples, most only a few millimetres long, as they were examining amber from the collection of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology in Drumheller, Alta. More came from amateur collectors who had been fossil-hunting for years.

The amber deposit is from the last days of the dinosaurs between 78 million and 79 million years ago.

Scientists have long known that some dinosaurs had simple feathers. Most of the evidence for that comes from fossils discovered in China.

Get daily National news

But those proto-feathers have been crushed into a thin film by the weight of millennia. In Alberta, however, the tiny filaments from both dinosaur and bird feathers that are embedded in the fossilized tree resin are so well-preserved that researchers can even guess what colour they were.

“All the specimens we’re seeing in Canadian amber appear to preserve some remainder of their pigments,” said McKellar.

“It looks like we’re seeing a range of colours – everything from white downy feathers to other birdlike feathers with grey or brown colours as well. And the proto-feathers tend to range from a sort of pale to dark brown colour. There could be other colours not showing up as a result of partial preservation.”

The dinosaur feathers don’t look that different from animal hair, McKellar said. They often consist of a simple, very fine central stem with filaments drifting off. Some forms having stems arranged in tufts.

But hairs they aren’t.

“One specimen contains more than 100 little hairlike filaments that are separate from one another and finer than mammal hair and lacking many of the structures you’d expect from mammal hairs,” McKellar said. “They’re not cellular. They don’t have little scales on them like you’d expect to see in mammal hairs.

“You don’t find mammal hairs in these sorts of tufted arrangements.”

Some of the specimens offer tantalizing clues as to their function.

The density of one sample suggests the dinosaur it came from used feathers to help keep warm. The coiled structure of another hints that the bird that lost it lived near water.

Scientists have theorized that feathers from some fledged dinosaurs weren’t that much different than those on birds living at the time. But the feathers in the University of Alberta study, from whatever dinosaur shed them, are primitive.

“We’re seeing some really, really primitive forms alongside a whole bunch of feathers that are very specialized and almost indistinguishable from modern bird feathers,” McKellar said.

Some scientists have long suspected most theropods – the big meat-eating dinosaurs that dazzle so many young imaginations – were feathered. McKellar said evidence from the fossil record that feathers were concentrated in this group is patchy.

But the wispy filaments preserved forever in southern Alberta may answer some of the questions about what the well-dressed dino was wearing toward the end of its long reign.

“It’s a question of what the non-bird theropods had for plumage,” said McKellar. “This seems to suggest that some held on to this primitive structure until the very end.”

Comments